with each [book], it has really taken, excuse the cliché, but a village to get the work distributed (p. 354).

Our press celebrates CCDP readers as part of that village, because distribution doesn’t stop at publication. Through CCDP readers, our authors’ ideas have traversed a variety of spaces–from articles to conferences to conversations. In this crowdsourcing initiative, we’re showcasing how our readers have extended the press’s impact into the classroom. We are featuring in our Scholar Electric blog pedagogical documents–like lesson plans, activities, and assignments–that were inspired by CCDP publications.

Amy Cicchino, whose activity was inspired by Courtney S. Danforth, Kyle D. Stedman, and Michael J. Faris’ Soundwriting Pedagogiessavanna.conner@asu.edu) and Mandy Olejnik (olejnimr@miamioh.edu) to submit assignments and ideas.

Sound-Mapping: Seeing the Rhetorical Choices in Podcasts

Dr. Amy Cicchino, Director of University Writing, Auburn University

This activity was originally implemented in a junior-level professional writing class. Students completed the activity at the beginning of a unit on media analysis, before they began composing an audio assignment.

Inspired by Danforth, Stedman, and Faris’ Soundwriting Pedgagogies (2018) collection, soundmapping helps students see the rhetorical choices that inform soundwriting by identifying and visually mapping the parts of a podcast. Soundmapping is like audio storyboarding. Specifically, this introductory activity helps students (1) identify and rhetorically analyze the different parts of a podcast; (2) learn the look of audio design program interfaces; and (3) begin considering the processes of brainstorming and drafting a piece of soundwriting (the thinking part that has to happen before anything is recorded or mixed).

Soundmapping is a good scaffolding starting point for soundwriting as it encourages students to enact Bunn’s (2011) Read Like a Writer techniques for audio texts. Reading like a writer—which in this case becomes listening like a soundwriter—encourages students “[to look] at the writerly techniques in the text in order to decide if you might want to adopt similar (or the same) techniques in your writing” and what effect those choices have on a reader/listener (Bunn, 2011, p. 72). Consequently, listening like a writer prompts students to identify the rhetorical choices the podcast creator(s) made and how those choices come together to create a cohesive experience of audio storytelling.

Before this activity

Identify a podcast in which an entire class would have interest. Often, I choose first episodes from a popular series (like Serial or 1619) or podcasts that have a general informative theme (like This American Life, Invisibilia, Mobituaries). Assign students to listen to a single episode or part of an episode as homework. Students should come to class with the following questions answered. This will provide a nice jumping off point to class discussion and create accountability for listening carefully to the assigned episode.

Questions

- What is the purpose of this podcast?

- Given this purpose, who is the most likely audience? Remember, be as specific as possible.

- Why would someone want to listen to this podcast? What would their motivation be?

- Identify the different sources of sounds that you heard in this episode in a list. This should include different speakers, effects, musical elements, and transitional noises.

- Did you think this podcast was effective in achieving its purpose for its audience? How do you know?

- Identify a moment in this episode where you felt the podcast was most rhetorically effective. Why did you choose this moment? What made it effective?

- When were there moments of confusion, ambiguity, or ineffectiveness for you? Do you think the podcast was intentionally confusing/ambiguous, or do you think these are instances of unintended miscommunication?

Activity

When students enter class the next day, we begin by getting into small groups and discussing our responses to the questions. I want them to practice applying rhetorical concepts to the episode, but I also want them to start considering what makes the genre effective. After discussing these questions, we delve into the deeper analysis of close reading the podcast through soundmapping.

Before class, I have selected a brief segment from the episode (typically, 1-3 minutes). I play the segment once just so we can all hear it again. Then, I explain that we are moving from listening to the podcast as an audience member towards thinking about how the podcast was put together, as creators. Our goal is to plot a diagram of the different sounds we hear, to create a kind of “map.” I compare our mapping activity to the work we do when we visually outline a piece of writing.

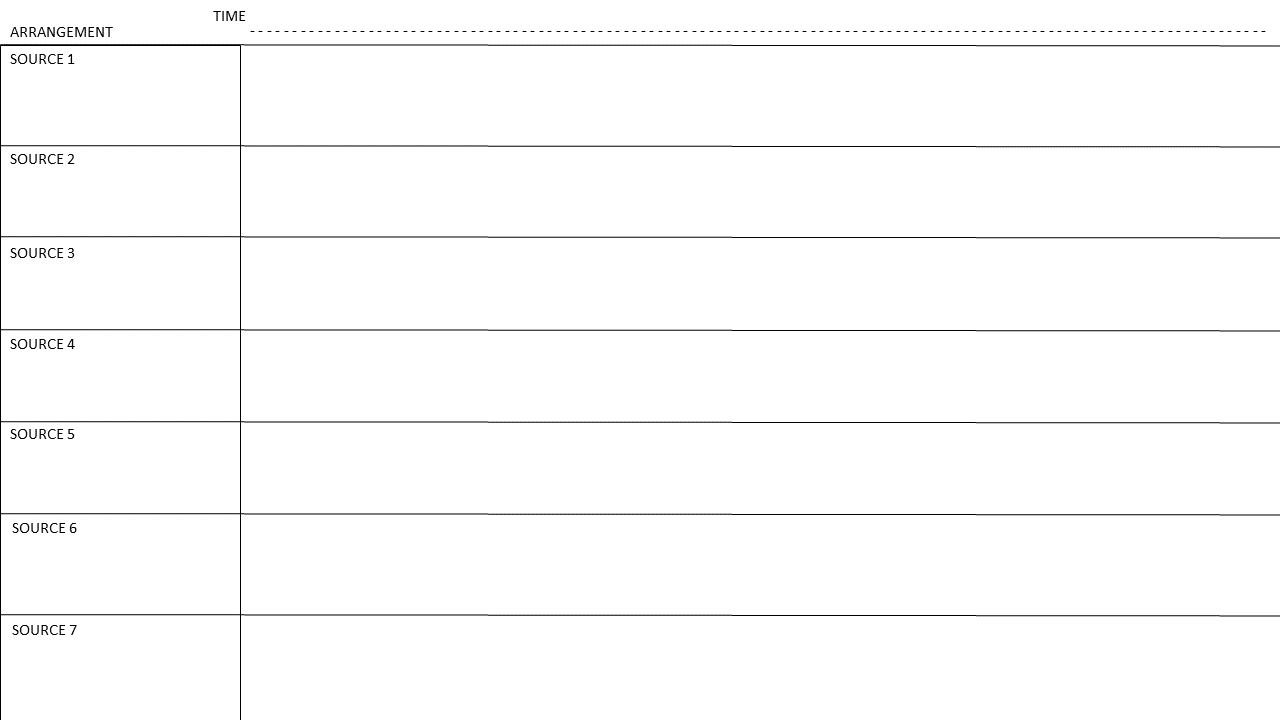

I distribute the soundmapping graphic organizer (Figure 1) and explain its general organization (which is meant to mimic audio-making interfaces).

Figure 1: Graphic organizer

We listen to the segment again with the goal of just marking how many sounds we hear and when they enter and exit the soundscape. This almost always takes multiple listenings. Then, students map fading in and out, as well.

Once we have our map, I break the students into new groups, and we tackle more nuanced questions about our map. These questions are recorded below.

- Focus on all of the different types of sound you see on your map. What rhetorical purposes do these different forms of sound serve? For instance, some podcasts use voices to attribute sources, as a kind of aural citation. Others use different sounds for mood. Others for organizational transitions and cues. Why do you think this soundwriter chose the sounds you see on the map in front of you?

- In your group’s opinion, do the sounds achieve their intended rhetorical purpose?

- Every aspect in a composition is a choice, and all choices have advantages and disadvantages. Choose one element in your soundmap and brainstorm in your group other things the soundwriter could have done to achieve their rhetorical purpose instead of what they did. What are the advantages and disadvantages of these other choices?

- Before you came into class today, you answered the following question: “Did you think this podcast was effective in achieving its purpose for its audience? How do you know?” Looking at your sound map, do you still agree with your initial evaluation of the podcast? How do you see this (in)effectiveness being enacted in the segment that we mapped?

- Did mapping the podcast show you anything new? In other words, did you “see” something that you hadn’t initially “heard?”

In the example that I’ve provided (Figure 2)—the opening to an episode of Reply All—the class might look at how an episode opens with conversational dialogue between the hosts that continues even as it interrupts the momentum that could pick up as the episode topic is introduced to listeners. This is pretty different than other potential podcast openings. Dramatic podcasts, for instance, use intro music and opening dialogue to place the listener within the topic from the very start. Some students might suggest that conversational interruptions are an ineffective way to open an episode, and they could be right if they identified the purpose of this episode was to transport the listener into a narrative. Reply All, however, might have a different identified purpose. If its purpose is to give listeners the impression that they are interacting with the hosts who are telling us a story, then the conversational informality reinforces that purpose. Analyzing podcast design as a series of rhetorical choices encourages the class to see the mapped choice as one of many possibilities. This discussion should then lead students to brainstorm other ways Reply All could achieve rhetorical purposes through different designs for their episode opening.

.png)

Figure 2: Model, completed graphic organizer

Often, considering the writing process can be difficult, especially when listening to soundwriting. Soundmapping can be a way to slow down and see the different rhetorical moves being made. It can double as a planning strategy for students before they begin mixing their audio for their own soundwriting pieces. Like writing, there is no one right process for soundwriting, but mapping gives students another mode for processing sound and a strategy to support their brainstorming and drafting processes.

References

Bunn, M. (2011). How to read like a writer. In Charles Lowe and Pavel Zemlianski (Eds.), Writing spaces: Readings on writing, vol. 2. (pp. 71–86). Parlor Press. https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/books/writingspaces2/bunn—how-to-read.pdf

Danforth, C. S., Stedman, K. D., & Faris, M. J. (Eds.). (2018). Soundwriting Pedagogies. Computers and Composition Digital Press/Utah State University Press. https://ccdigitalpress.org/soundwriting

Our first showcase comes from

Our first showcase comes from