As an opening act for our journey through scenes of captioned and subtitled accessible multimodal and multilingual communication, this chapter presents an examination of two contexts formative in the development of the original criteria for the analysis of integral captions and subtitles. Two examples from contemporary popular media—Heroes Reborn and Sherlock—are assessed to reveal the ways the use of integral subtitles embody each show’s respective hybrid worldviews and the fluid interplay of communication modes. Heroes Reborn provides English-using viewers with visual access to spoken Japanese through English subtitles on screen while Sherlock integrates visual text and subtitles in scenes in which languages and modes other than spoken English play out on screen.

The integration of subtitles may be most rhetorically and aesthetically effective in multilingual and multicultural contexts. Subtitles that are moved or placed into the spaces around and between bodies in conversation make more salient the verbal and embodied interconnections between languages and cultures. As mentioned in Chapter 1, subtitles (and captions) are integral to a video when space has been designed for subtitles during the production and editing process, subtitles provide visual access to performers’ bodies and facial expressions, and subtitles embodies the multimodal nature of communication in the video (Butler, 2018).

To study the effective design of subtitles that are aesthetically and rhetorically integral to the meaning of a composition, reviewing the six criteria of the embodied multimodal approach may be helpful:

- Space for Captions and Subtitles and Access

- Visual or Multiple Modes of Access

- Embodied Rhetorics and Experiences

- Multimodal (including Multilingual) Communication

- Rhetorical and Aesthetic Principles

- Audience Awareness

Subtitles can be designed1 to immerse viewers into the multilingual and multimodal interactions amongst bodies and modes. Integral subtitles interact with, rather than remain below—or subservient2 to—the content of the video. At the same time, while the visual text on screen may enable certain viewers to visually access the meaning within the space of the screen, we can make these media even more inclusive by creating audio descriptions that vocalize the visual text and make the content aurally accessible.

HEROES REBORN: EMBODYING THE SPATIAL PROXIMITY OF IMAGES AND TEXT IN COMIC BOOKS

The embodied multimodal approach will now be applied to what I consider one of the most effective designs of integral subtitles in contemporary media. The 2015–2016 miniseries Heroes Reborn is a follow up to NBC’s 2006–2010 science fiction hit Heroes; this show, like its predecessor, features an international ensemble of characters in a science fiction program about individuals with special powers.

In Heroes Reborn, one of the protagonists, Miko Otomo, speaks Japanese. Her Japanese conversations with her father, Hachiro Otomo and friend, Ren Shimosawa, are subtitled in English. However, in contrast to traditional subtitles at the bottom of the screen, these subtitles are designed to be visually engaging and draw the eye around the action on screen. Continuing the subtitle design tradition that began with the original Heroes, this series successfully integrates the subtitles into the composition of the show, as shown in Figures 2.1 and 2.2. This further allows English-speaking audiences to join these characters and their embodied conversations.

Figure 2.1: Subtitles next to characters and their gaze in Heroes Reborn

Figure 2.2: Subtitles next to characters and their gaze in Heroes Reborn

In scenes such as these, the spatial proximity of the subtitles to Japanese speakers’ faces and body language intensifies the articulation of their statements; although these characters are speaking in Japanese, sighted viewers immediately see their statements translated into English on screen. Instead of a temporal-spatial gap in going from one language to another at the bottom of the screen, viewers visually access the embodied rhetorics of the Japanese speakers and their intentions in spatial proximity. The subtitles draw viewers not only to characters, but to their message and the spirit of the show.

Heroes Reborn embraces the influence of graphic novels, manga, and digital games in storyline content and visual design. The interplay of visual and textual modes certainly may be at its most salient in comic studies, as words can be placed to guide readers through their interaction with the page (as revealed in the 2015 Composition Studies special issue on comics, as well as Losh et al.’s 2020 graphic textbook, Understanding Rhetoric).

The design of the subtitles in Heroes Reborn capitalizes on the affordances of the live-action genre of videos by integrating visual text into the space and temporal sequencing of its scenes. The show’s use of visual text is not limited to foreign language subtitles, extending to descriptive text on screen that indicate the time or location of the scene. In one scene, “Odessa suburbs” appears painted on the wall that a woman character then walks in front of and obscures as she passes the words. In another scene, lines of text explaining that another character is now 7,000 years in the future expand in size as they three-dimensionally fly off the screen into our viewing space, drawing our eye into the scenery behind the words. The interaction of visual text with action on screen resembles the visual-verbal interplay of modes in graphic novels, comic books, and manga3. In this way, Heroes Reborn embodies the hybrid, interactive culture of these texts and strengthens its rhetorical message as a show that blends cultures, genres, and (superhero) abilities.

Capturing how subtitles move with the action on screen in one scene of Heroes Reborn, the line, “The sword is not yours” is slanted in alignment with the sword that the speaker refers to, as shown in Figure 2.3. Since we view the sword and the speaker from the main character Miko’s perspective lying on the ground after losing a battle, the slant and alignment are effective in aesthetically and rhetorically conveying the misalignment she senses at the moment.

Figure 2.3: Alignment of subtitles and scene

The design of the English subtitles for Japanese speech is rhetorically and aesthetically effective in terms of the placement on screen, the typography, and the pacing. The subtitles sometimes appear on the bottom of the screen, but mainly are placed around the screen as the characters converse or move around each other. By tracing the characters’ actions and remaining near their faces, the subtitles keep our eyes with the action on screen. The effect is that the visual design is enhanced and the rhetorical content is more accessible.

The bold white typography for the integral subtitles is clear and readable in a variety of lights and settings. This shows effective design consideration in allowing the subtitles to be placed around the screen in different conversational and social contexts. This makes them—from a design perspective—more readable than white subtitles that are added on after the fact and sometimes are difficult to read when read on top of a light compositional background, as will be revealed in the next section’s exploration of Sherlock.

The subtitles do not seem to have a singular placement strategy that is used in each episode or scene. During any conversation or single speaker’s statements, the subtitles may appear at any location on screen. This is not disruptive since the subtle changes in placement keep the eye engaged around the video composition. This seems to be the intention—to purposefully not pull the eye down to the bottom of the screen and instead to maintain our visual engagement in the action and the characters’ faces as they navigate through genres and modes in the science fiction world of the show. As such, the visual/textual hybridization in the Japanese-language scenes in Heroes Reborn can be explored through the embodied multimodal approach and its six principles: space, visual access, embodied rhetorics, multimodal/lingual communication, rhetorical and aesthetic qualities of a video, and audience awareness.

The hybridization begins when we first meet Miko at the same time as Ren. Ren opens the door into her residence and they immediately engage in a back-and-forth conversation figuring out who the other is (Kring & Shakman, 2015). The sudden immersion into their storyline is accompanied by subtitles that stand high up on the screen right next to their faces. The location of the subtitles is appealing and draws the eye not only into the novelty, but also into the intriguing dialogue between two characters who are meeting for the first time as we also meet them for the first time. In this way, and as shown in Figures 2.4 and 2.5, the subtitles embody the multimodal social interaction of two individuals facing each other for the first time.

Figure 2.4: Subtitles that show characters meeting each other for the first time

Figure 2.5: Subtitles that show characters meeting each other for the first time

The first scenes between Miko and Ren, integrally subtitled, set up the hybridity and fluidity of their worlds. After entering her apartment, Ren tells Miko that he is a gamer and an expert at the game Evernow. He unlocked a secret message that gave him Miko’s address. Despite her confusion, he realizes that she is Katana Girl. After she kicks him out of the apartment, he soon returns with a copy of a manga about Katana Girl. As soon as she opens the door, Ren declares that she is Katana Girl from the manga series that her father created. After recognizing herself in Katana Girl, Miko unearths a katana (a Japanese sword) in her father’s study and is transported into the digital game, where she enters into battle with the katana.

Miko’s ability to immerse herself and viewers in the game’s digital space is reflective of how Heroes Reborn blurs the boundaries between reality, manga, comic books, and digital games. Such immersion complements scholarship in comic studies that interrogate the spatial arrangement of images and text (word balloons and captions) and how their relative positions can draw viewers through the page as they attend to the characters (Groensteen, 2007; Humphrey, 2015; among others).

The strategic placement of subtitles near faces and bodies in Heroes Reborn makes the intentions of characters even more apparent. When Miko and Tommy converse in English about saving the world, she mentions a crucial element that identifies her as Katana Girl—the ribbon in her hair that her father gave her—and points to the ribbon in her hair, as shown in Figure 2.6 (Elkoff & Kondracki, 2016). The subtitle for this word appears in the space created by her arm pointing to her head, purposefully directing viewers’ eyes to the meaningful physical element that we need to attend to: the significant ribbon.

Figure 2.6: Strategic placement of a word within an embodied space

The design of the integral subtitles in Heroes Reborn enhances the viewer’s ability to follow the interactions between bodies, which makes them more successful in rhetorical, aesthetic, and accessible terms. The most successful rhetorical element of the subtitles is the consistency with which the subtitles are consciously placed close to speakers’ bodies, and perhaps more importantly, their faces. The subtitles do not simply co-exist on screen; they are synchronized with the spoken words and visible emotions that appear and disappear from the characters’ bodies. The visual proximity of text and speech aligns the speakers with words and allows viewers to follow the dialogue between Miko, her father Ren, and at times Hiro Nakamura, with ease and pleasure.

Throughout the episodes, the subtitles are integrated into the show in various ways, some more rhetorically successful than others. For instance, when two characters are engaged in dialogue, the subtitles are frequently placed in the space created between the bodies to show the co-creation of meaning. When a character moves out to one edge of the screen or directs her attention to another edge (as shown in Figures 2.7 and 2.8), the placement of the subtitles gravitates our eyes towards each direction.

Figure 2.7: Strategic placement of words at each side of Miko to embody her search

Figure 2.8: Strategic placement of words at each side of Miko to embody her search

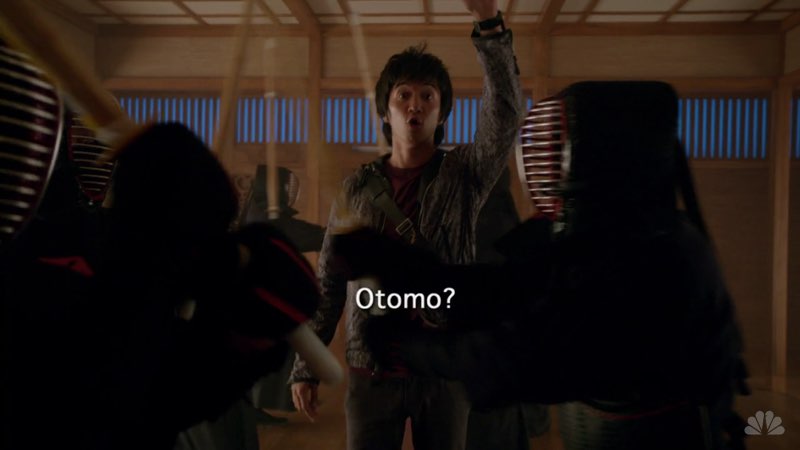

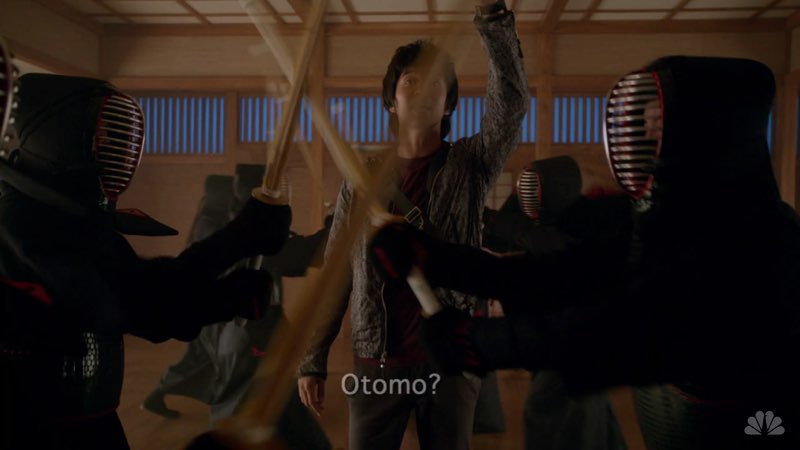

There are effective moments in which the subtitles subtly and cleverly interact with the action on screen to maintain the flow of action and eye gaze. In addition, there are several moments that stand out as being especially aesthetic use of subtitles that embody the action on screen and the ways that hybrid genres direct viewers’ eyes in nonlinear forms. For instance, when Ren helplessly watches Hachiro Otomo walk away from him, his fruitless calls to “Otomo” fade and drift down the screen (Fahey & Kondracki, 2015). The fading movement of the subtitles visually reinforces that his voice is not being attended to by Otomo and that his voice is disappearing into thin air as Otomo ignores him, as shown in Figures 2.9 & 2.10.

Figure 2.9: A question that visually falls and fades out in front of Ren

Figure 2.10: A question that visually falls and fades out in front of Ren

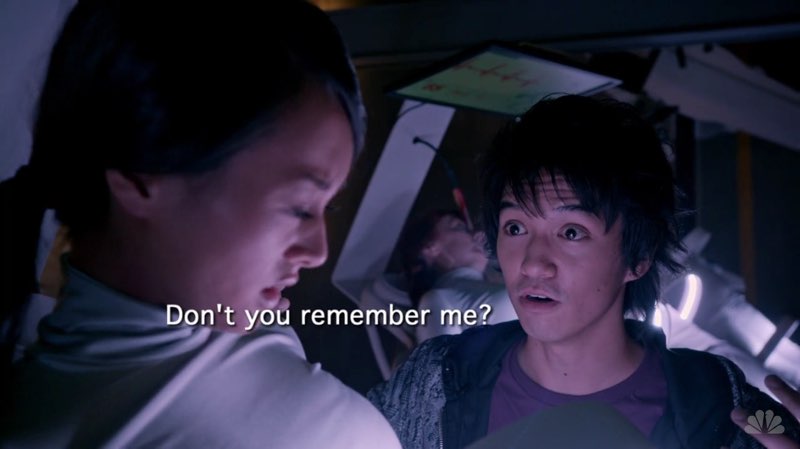

Such syntheses of physical and textual embodiment indicate the potential for subtitles in animated, live-action genres beyond print graphic novels and comic books. Subtitles not only can synchronize with the action on screen, they can also accentuate viewers’ responses. In a pivotal moment, Ren finds an unconscious Miko and excitedly talks to her with the subtitles popping on and off screen as she recollects herself. He realizes that she doesn’t seem to recognize him and states, crestfallen, “Don’t you remember me?” These subtitles fall in a floating and graceful way down the screen with the final question mark directing our eyes to Ren staring at her in disbelief and sadness (Figures 2.11 and 2.12).

Figure 2.11: Another question that visually falls and fades out in front of Ren

Figure 2.12: Another question that visually falls and fades out in front of Ren

Viewers are shown Ren’s crestfallen face, which is magnified by the subtitles that seem to have lost all their energy and air. The design of the subtitles is thus effective in aesthetically and rhetorically paralleling his current embodiment and appealing to audiences’ emotions.

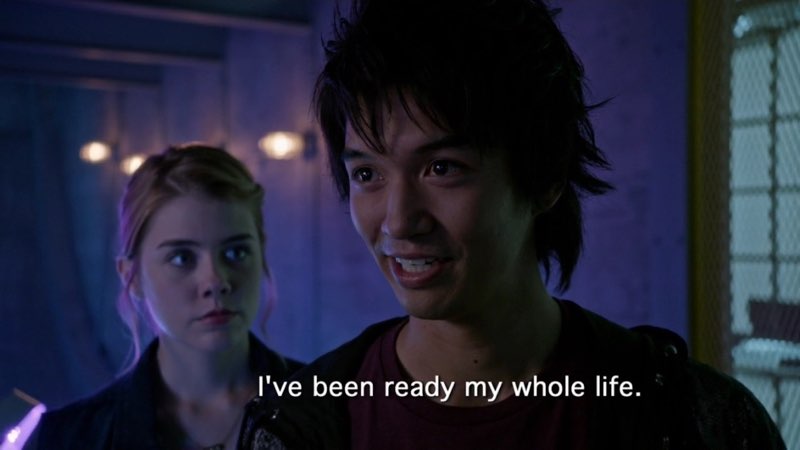

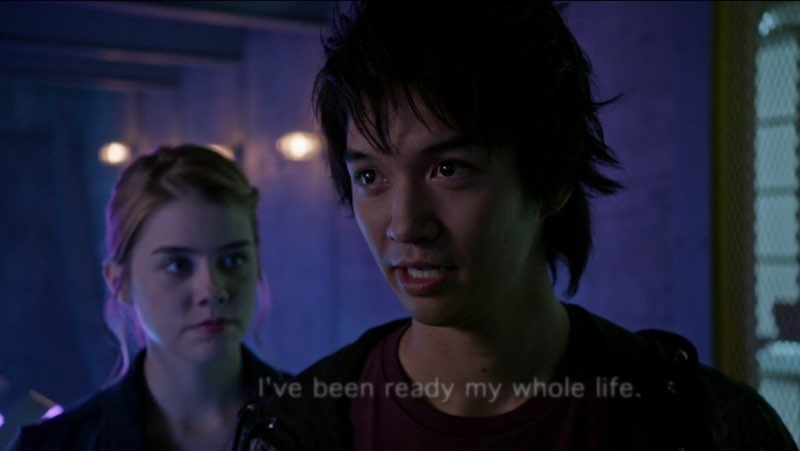

The spatial movement of embodied subtitles continues in a scene in the miniseries’ final episode. The subtitles allow viewers to sense Ren’s discovery of self-confidence when Hachiro Otomo puts all his faith in Ren’s ability to enter “Evernow” as a warrior in their final mission. As Figures 2.13 and 2.14 depict, Ren’s confident look is reflected in the subtitles, “I’ve been ready my whole life” when the subtitles fade out in sync with a rise in what the closed captions describe as dramatic music. Instead of a question that literally falls downward, he makes a strong statement that stays in line on screen and that embodies his steady confidence.

Figure 2.13: A statement that does not fall down and that shows Ren’s steady confidence

Figure 2.14: A statement that does not fall down and that shows Ren’s steady confidence

This climatic synchronization of emotion, music, subtitles, and live action is followed by Ren and Miko transporting into the digital game as warrior versions of themselves.

The characters’ ability to enter digital games or identify themselves in manga and comic book series reflects the integration of the visual and verbal in hybrid genres and represents the creators’ awareness of audiences who are watching this genre of a science fiction show. The integral subtitles in Heroes Reborn serve as an effective example of how we can likewise integrate subtitles in rhetorical, aesthetic, and visually accessible ways to express our multilingual identities and connect with multilingual audiences through subtitles that engage with bodies and languages on screen. Subtitles can be used to strengthen multimodal messages to audiences in the ways that this science fiction show’s use of integral subtitles strengthens the series’ emotional content and message about the fluidity of worlds, genres, and modes.

JUXTAPOSITION: INTEGRATING AND MOVING WITH SUBTITLES

Studying integral subtitles in a multilingual program can inspire creators to develop effective rhetorical and aesthetic strategies for incorporating subtitles in other contexts, including professional and academic contexts. These thoughts are fundamental in my video for this chapter, which I now invite you to play. As you watch the video, consider how creators can incorporate subtitles that create access to embodied and multilingual communication.

One moment in this video highlights how we can learn to develop strategies for accentuating the rhetorical and aesthetic message of a multimodal composition. I describe a subtitled moment in Heroes Reborn in which Miko walks through a space calling out “Hello?” and the subtitles appear on two sides of the screen, directing viewers’ gaze. While recording my video, I physically moved myself and my hands to replicate this performance. I consciously moved from one side of the frame to the other and signed the word “Hello?” with attention to where the subtitles would appear in different spaces throughout each moment of this performance. To emulate this scene from my analysis of Heroes Reborn and to ensure that viewers could attend to the correct space of my screen, I placed the subtitles for “Hello?” near my face and arms as I signed the word.

My analysis and emulation of a program’s integral subtitles in this video is an example of how to balance rhetorical and aesthetic qualities in professional contexts while guiding viewers’ attention and without detracting from the purpose of a video. Multimodal and multilingual movements in interaction with subtitles can be activities that celebrate our embodiments (our experiences of the world) and our embodied rhetorics (how we communicate with each other). And we can continue to learn from programs that have effectively integrated subtitles to embody the show’s worldview, from Heroes Reborn to Sherlock, the latter of which we will explore in the second half of this chapter.

SHERLOCK: A STUDY OF WORD AS IMAGE

The BBC series Sherlock, which aired 14 episodes from 2010 to 2017, places the title detective and his companion, Sherlock Holmes and Dr. John Watson in modern-day London. The spirit of the original stories remains true with Sherlock and Watson solving crimes, and the first episode immediately immerses viewers into the genius detective’s perceptive worldview. For instance, when Sherlock observes bodies and materials for clues, words representing his deductions float around different elements of the body. This strategic fusion of word and image reflects Sherlock’s way of identifying connections between objects and bodies in the world.

Sherlock drew positive attention for its predominant use of visual text on screen (McMillan, 2014) such as text messages that appear next to characters’ bodies during the episodes airing between its premiere in 2010 and 2014. In January 2016 a special episode aired, “The Abominable Bride” (Moffat et al., 2016), that featured a scene with integral subtitles in which the characters communicate in British Sign Language (BSL). Subtitles directed the viewer’s eyes to the characters’ signs and facial expressions. However, one subtitled scene was not imposed without warning; instead, it seamlessly continues the show’s practices of integrating visual text on screen in many of its scenes.

First, let’s discuss the series’ use of visual text to reinforce how the hybridization of visual and verbal on screen embodies Sherlock Holmes’ approach to reading the world through words and images. As embodiments of multimodal meaning, the integration of visual text is important for understanding the strength of integral subtitles in making meaning visually accessible. Throughout this analysis, keep in mind that audio description must be provided when visual text appears on screen to ensure equitable access. At the same time, Sherlock can be utilized as a unique instance of a show designed by hearing individuals that embodies the fluidity of accessible multimodal communication.

Entering an Immersive World

In the first episode, “A Study in Pink,” the camera fluidly follows Sherlock’s movement through spaces, from inside the apartment as he leaves to the world of London on the street; later he enters another apartment to a crime scene (Moffat & McGuigan, 2010). When characters are traveling in a car, the camera frames them from outside the car so that viewers observe the characters through the car window and the reflection of the visual cityscape that they are moving through on the windowpane. The continual fluidity of embodied movement through space accentuates the sense of experiencing the world through our eyes and bodies.

The series stands as one of the earlier chronological examples of a series that integrates written and typed messages into the space of the screen, and this fusion enhances the fluidity of the camera as it moves through scenes. When someone gazes at their phone or reads off their computer, the camera does not cut to a shot of the phone or the computer; instead, the message appears on screen in white text. The result is a seamless integration of visual text and the space of the screen.

For instance, in “The Sign of Three,” Detective Inspector Lestrade is alarmed when he receives two texts from Sherlock pleading for immediate help (Thompson et al., 2014). The camera looks up at his body from the ground, creating a sense of disorientation that is reinforced by the placement of the text messages on Lestrade’s body. As shown in Figures 2.15 and 2.16, disorientation reflects Lestrade’s own disorientation—as shown on his face—in needing to leave an important arrest in order to help Sherlock.

Figure 2.15: Framing the disorienting sense of receiving alarming text messages in Sherlock

Figure 2.16: Framing the disorienting sense of receiving alarming text messages in Sherlock

By physically keeping the text message with Lestrade, instead of separating the words from his feelings, this design strategy embodies the rhetorical message of the moment: Lestrade is (and viewers are) disoriented by what he has just read. Instead of cutting the camera away to a close shot of the character’s phone—which disrupts the viewer’s attention to the character’s face, and his reaction to the text message—the structure makes it possible for viewer to read the text message and the character’s reaction to the text message simultaneously without losing a sense of how the message affects the character and the scene.

Figures 2.17 and 2.18 show another scene where Detective Inspector Lestrade has a visible response to a text message that Sherlock has just sent him. Instead of drawing viewers eyes away from the embodied moment, the text message moves with his body and facial expressions.

Figure 2.17: Framing the disorienting sense of receiving an even more alarming text message

Figure 2.18: Framing the disorienting sense of receiving an even more alarming text message

The most visually effective programs, including Sherlock, have designed the text messages so that only the words along with a clear display of a phone screen appear on screen. In this way, the words become a part of the scene and a component of communication. The seamless incorporation of text messaging on screen in a growing number of recent shows reflects the potential for integral captions and the hybridization of visual and text in contemporary culture.

The integral and strategic use of visual text on screen seems to have originated from a simple purpose. In an interview with Wired UK magazine, Sherlock producer Sue Vertue explains, “It was really as simple as [director] Paul McGuigan not wanting to do close ups of a whole load of phones whilst we read the texts” (McMillan, 2014, n.p.). In the same interview, Vertue notes that the first episode, “A Study in Pink,” featured the most use of visual text in the first season because it was the last one to be written and filmed. The first episode to be filmed, “The Blind Baker,” didn’t use visual text as much “as it had already been written, and the script didn't lend itself so easily to the style in post-production” (McMillan, 2014, n.p.).

In contrast, “A Study in Pink” was designed to have visual text and so it “could make the best use of onscreen text as additional script and plot points, such as the text around the screen of the pink lady” (McMillan, 2014, n.p.). The contrast between these two episodes becomes a salient example of how integral captioning must be a design consideration from the very beginning of the drafting and filmmaking process. The first episode that was filmed could not incorporate visual text after the fact while later episodes designed a space for visual text; these later episodes are strengthened by the incorporation of visual text that hybridizes word and image.

Sherlock’s embodied rhetorics—his interactive interpretation of the world through close observation—are reflected in the interlaying of clean white font and action on screen. As Sherlock tells Lestrade in “The Great Game” when the Detective Inspector has trouble understanding Sherlock’s point, “You do see, you just don’t observe” (Gatiss & McGuigan, 2010). We may see dead bodies as images on screen, but through the lens of Sherlock, we observe specific clues; in a particular scene in “The Empty Hearse,” Sherlock sniffs the air around a dead body for clues. The word “Pine?” emerges in the space around him until it is knocked up and out by the word “Spruce?” that in turn is knocked up and out by the statement, “Cedar.” This textual visualization embodies Sherlock’s mental processing of the world as word and image, and this is recreated throughout the various episodes of the series.

While articles, blogs, and reviews at the time responded positively to Sherlock’s visual text and integration of text messages (Banks, 2012; Bennet, 2014; Calloway, 2013; Dwyer, 2015; McMillan, 2014), an embodied multimodal approach reveals how the integrated visual text and subtitles in the BSL scene immerse audiences into Sherlock’s rhetorics and the way he makes meaning through mixing various modes. Sherlock embodies the fusion of image and text (Mitchell, 1994), or image and word (Fleckenstein, 2003); in other words, how we make meaning and interpret the world through a multidimensional synthesis of images and words. The fluid interplay of visual text and images in Sherlock guides viewers through Sherlock’s worldview as he, and we, bring alphabetic text into the visual mode and vice versa.

Certain scenes seem to indicate that space was designed explicitly for visual text during the filmmaking process. In “The Reichenbach Fall,” Sherlock is in a laboratory with bright white lighting and washed-out background. The text messaging, which appears as a white font on screen, is placed exactly in the dark area created by a bottle in the laboratory (Thompson & Haynes, 2012). This clear design consideration attends to making visual text accessible to viewers. In the same scene, Sherlock is seated with his feet up on the desk next to him and the text message appears in the open triangular space created by his body.

The integration of visual text embodies Sherlock’s mentality in a particular scene in “The Empty Hearse” in which Sherlock is tied up and being interrogated by Serbians in a dark scene (Gatiss & Lovering, 2014). The foreign language subtitles for the Serbian speakers appear in conventional form on the bottom of the screen and are not integrated into the scene itself. This seems to be an embodiment of Sherlock’s mentality because in this moment, Sherlock’s hands are bound to his side and he is bent forward. Figure 2.19 portrays how Sherlock cannot sense the world panoramically at this moment and the design of the subtitles reflect his isolation from any meaning in the world.

Figure 2.19: Traditional subtitles at the bottom of the screen

The conventional design of the subtitles for the Serbian language embodies Sherlock’s inability to process the world in contrast to other scenes in the special episode, “The Abominable Bride” (Moffatt et al., 2016). This episode sets the characters in Victorian England (and near the end of the episode, viewers discover that the episode was a dream that took place in Sherlock’s mind). This translates the series’ visual integration of text messages to the historical context in scenes in which recipients open handwritten and telegram messages sent on paper. When characters read these messages, visual text appears in the space next to them, allowing the audience to read the message and characters’ responses at the same time, as in Figures 2.20 and 2.21.

Figure 2.20: Handwriting on screen showing words that are being read at the moment

Figure 2.21: Handwriting on screen showing words that are being read at the moment

Silent Communication

Sherlock’s multimodal way of communicating across modes and even languages reaches its apex in a scene in this episode, “The Abominable Bride.” An embodied multimodal analysis of this pivotal scene is strengthened by its setting within the series’ theme of multimodal interpretation of the world.

In this scene, Sherlock, Watson, and a porter named Wilder engage in an extended conversation in British Sign Language (BSL) with none of them moving their mouths. Although we have never seen the two main characters sign until this moment in the series, the silent conversation is treated as natural and not out of the ordinary by the characters since the characters never comment on the signed exchange before or after the scene. Sherlock’s ability to sign and the integration of subtitles around their bodies embodies his fusion of word and image, of language and signs.

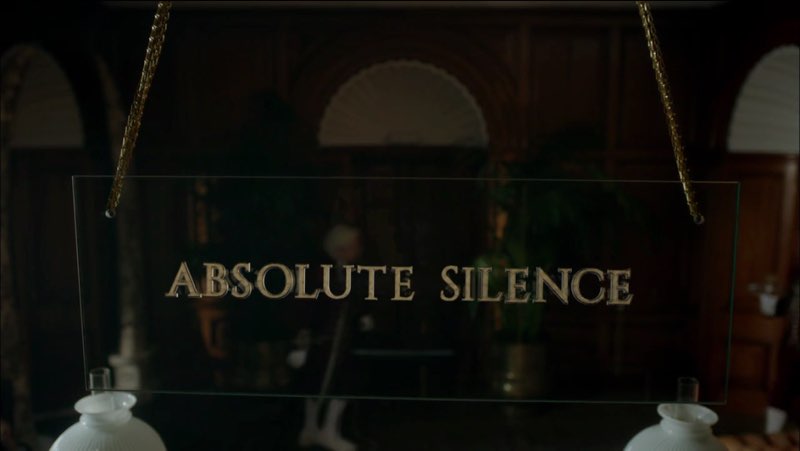

Sherlock and Watson enter the Diogenes club and the letters on the plaque rearrange before our eyes to another plaque that reads “ABSOLUTE SILENCE.” The visual text, as shown Figure 2.22, explains the purpose: members cannot speak within the club.

Figure 2.22: Silence being requested through written words

Sherlock engages in a signed conversation (in BSL) with the man at the front desk, a porter named Wilder, as shown in Figures 2.23 and 2.24. Sherlock signs fluidly and comfortably and Wilder responds with equal level of comfort. The subtitles organically accompany their bodies and appear in the space along their bodies—not at the bottom of the screen. They scroll out as they are being signed instead of popping on and off screen, which creates ease in following the conversation without disrupting the flow of the overall narrative. The scrolling motif allows for words to appear on screen in tempo with the signs and the cadence of the conversation, enhancing the aesthetic design of the scene.

Figure 2.23: Subtitles next to signers for a conversation in British Sign Language

Figure 2.24: Subtitles next to signers for a conversation in British Sign Language

As a viewer who does not know BSL, I found the subtitles effective in spatially guiding me through the conversation and temporally through the specific signs that appeared on screen at the same time as the words. The proximity of words and signs (of two languages and images) succeeds in embodying Sherlock’s fusion of word and image and communication as visual, spatial, and linguistic.

While the actors who play Sherlock (Benedict Cumberbatch) and Dr. Watson (Martin Freeman) learned BSL signs specifically for this scene (O’Brien, 2016), the coordinated placement of BSL and subtitles in this scene certainly is an indication of Deaf Gain, or how mainstream society can benefit from Deaf perspectives and experiences. Leigh et al. (2014) write that Deaf Gain provides a “way of relating to the world through the eyes in addition to the other sensory experiences the human body and culture make possible” (p. 359). This certainly seems true in this scene, which shows how integrating embodied subtitles on screen benefits hearing and DHH viewers on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean by showing what is being signed on screen and how well or not well it is being signed by the characters.

The proximity of word and image makes the crucial moment of the scene visually accessible and underscores the rhetorical message: that Watson is not an expert in BSL. The humor begins when Sherlock introduces Watson to the porter, who compliments Watson's publication. It is immediately clear that Watson is not as adept in sign language as the other two. The camera frames Watson's upper body (above his waist) and the subtitles appear next to his head and shoulders, making the synchronization of signs and words as clear as possible to viewers. As Figure 2.25 depicts, Watson signs back, “Thank you. I...am...glad...you...liked it.”

Figure 2.25: Lack of full confidence in a language made evident through ellipses.

Watson continues to be oblivious to his incorrect signs. He inadvertently insults the porter’s appearance several times while also mis-signing the name of his own publication. The following images depict the porter’s confusion and Watson, who continues to state nonsense like “I am glad you liked my potato.” The spatial closeness between the signs and words appearing on screen allows for our eyes to see the word “potato” and also immediately see in the same space Watson signing “potato.” This allows for us to see him signing with the reaction that Sherlock and Wilder have: puzzlement. However, as Figures 2.26 and 2.27 show, the brightness shining in from the window next to the porter can hinder the readability of part of the subtitles. This limits the full effectiveness of these subtitles.

Figure 2.26: Miscommunication made evident through subtitles

Figure 2.27: Miscommunication made evident through subtitles

The subtitles’ placement and temporal pacing allow the viewer to experience the actors’ embodied performances, including the differences in signing fluency.

The scene and the integral subtitles end with Sherlock staring at Watson who breaks the code of silence and says “Sorry, what?” as Sherlock walks away. This spoken line is not accompanied by integral subtitles, although the spoken line appears in closed captions at the bottom of the screen. Also, the signed scene did not include closed captions at the bottom of the screen because no messages were spoken in this scene—until Watson spoke.

After Sherlock walks away, Watson then gives the porter an awkward thumbs up and follows Sherlock out of the room. The scene would not have the same significance to viewers—and the rhetorical message would not be as successful if the subtitles were conventionally placed at the bottom of the screen. If all viewers had to draw their eye to the bottom of the screen to read “I…am…glad…you…liked it” and “I am glad you liked my potato,” they likely would not have fully appreciated the humor and awkwardness of the situation. The design of the integral subtitles thus embodies the process of making meaning through multiple modes and languages.

The six principles of the embodied multimodal approach have been implemented here. As in other scenes in this and previous episodes of Sherlock, space has been designed for visual text throughout the filmmaking process. We sense multimodal and multilingual communication in interaction through BSL and English words on screen. The scrolling motif and proximal placement of the subtitles enhance the rhetorical and aesthetic qualities of this silent scene. Finally, the scene shows awareness of how audiences who are not fluent in BSL could engage with the performance visually.

Open Subtitles and Closed Captions

The integration of subtitles in the signed scene in “The Abominable Bride” stands in stark contrast to how the closed captions in the prior and posterior scenes are portrayed. Again, closed captions are traditional captions that appear at the bottom or top of the screen only if the viewer has turned them on. In the prior scene Watson is talking to a maid and, as Figure 2.28 shows, the placement of the closed captions divides the viewer’s attention between the bottom of the screen and the woman’s facial expression near the top of the screen.

Figure 2.28: Closed captions at the bottom of the screen away from the speaker’s face

In the next scene Sherlock and Watson are talking to Sherlock’s brother Mycroft and viewers see them from behind Mycroft’s figure. Again, the closed captions appear around Sherlock and Watson’s knees, regardless of who is speaking. The contrast between the sandwiching scenes is so striking that it is almost as if the distance between bodies in the sandwiching scenes were designed on purpose to reinforce the proximity of embodied rhetorics in the signed scenes.

The integral visual text and subtitles in Sherlock fuse with the imagistic composition to guide viewers through Sherlock’s interpretations of the space around him. Taking away the visual text—and the subtitles in the signed scene—would deprive each scene of its organic meaning and prevent viewers from being able to access Sherlock’s mind. Instead, the words on screen allow us to experience Sherlock’s embodied rhetorics and become the close observer of the world in all its forms, modes, and languages.

COMMUNICATING THROUGH MULTIPLE LANGUAGES

Sherlock and Heroes Reborn are distinctive examples in popular media that show composers—media creators, instructors, scholars, students, content creators—innovative approaches for integrating subtitles that embody multimodal and multilingual communication. We can, as Sherlock and Heroes Reborn have, embrace the hybridity/fluidity of image and text to embody how we interdependently work to understand each other through multiple languages and modes. When we engage in dialogue in videos, whether through presentations, dialogue, interviews, or other contexts, captions and subtitles can be integrated to make our rhetorical and aesthetic world accessible while demonstrating our value for audiences who communicate across different languages and modes.

The signed scene in Sherlock, created and performed by hearing individuals, certainly reveals the Deaf Gain that comes from designing a space for subtitles that embody a scene’s message.