While the previous chapters centered on integral captions and subtitles as the epitome of embodied accessible multimodal communication, it is imperative to recognize that highly aesthetic and stylized design of captions and subtitles may not be feasible or appropriate in certain contexts. Our world is full of contexts and media in which closed captions and open captions and subtitles at the bottom of the screen are rhetorically and aesthetically effective. Captions and subtitles might not be placed next to characters’ faces or appear in temporal synchronization with speech or signs, but they certainly embody the value of accessible multimodal communication.

This chapter presents a case study of a significant example in which two characters on a mainstream television show engage in the interdependent process of learning to communicate with each other; concurrently, the audiences engage in this interdependent process through accessing closed captions and open subtitles at the bottom of the screen and other visuals on screen.

In the multilayered scenes of NBC’s New Amsterdam, how the characters communicate with each other through multiple modes of meaning embodies the reality of our lives as we work together to understand and empathize with each other across languages and differences.

The six criteria of the embodied multimodal approach are synthesized throughout this case study:

- Space for Captions and Subtitles and Access

- Visual or Multiple Modes of Access

- Embodied Rhetorics and Experiences

- Multimodal (including Multilingual) Communication

- Rhetorical and Aesthetic Principles

- Audience Awareness

This chapter’s analysis of the progression of the relationship between two characters in New Amsterdam reflects the interdependent reality of our lives as we bridge meaning across modes, technologies, and languages. Like Dr. Max Goodwin and Dr. Elizabeth Wilder, we can accept the challenges of designing access and the possibilities for forming deeper connections across multiple modes of engagement with each other.

NEW AMSTERDAM: SETTING THE SCENE

New Amsterdam is a hospital-centered show (and the name of the hospital) that aired on NBC for five seasons starting in 2018 and stars Ryan Eggold as Dr. Max Goodwin. Over the first four seasons, audiences watch Max advocate for the rights of his patients as he loses his wife and falls in love with a colleague, Dr. Helen Sharpe (played by Freema Agyeman), only to have Helen abruptly abandon him and leave the country.

At the beginning of the fourth season, viewers are introduced to Dr. Elizabeth Wilder, a Deaf oncologist played by Sandra Mae Frank, who is Deaf. While Frank initially appears in only three episodes in the first half of the fourth season, she appears in the entire back half of the fourth season in the last 11 episodes and becomes a full-time character for the entirety of the 13-episode fifth and final season.

Throughout the fourth and fifth seasons, Wilder interacts directly with the other characters at New Amsterdam with the presence of Ben Meyer, her designated interpreter (played by Conner Marx). Her colleagues, patients, and others address her directly with Ben in the background voicing Elizabeth’s signs and signing their spoken words. This portrayal modeled effective communication across ASL and English in real life, and closed captions could be turned on by viewers to access the spoken English.

At the start of the fifth season, a remarkable progression begins to occur as Wilder and Goodwin communicate more frequently and grow closer. In tandem with the growth of their friendship is the increased use of multiple modes of communication on screen, and the layers of modes of meaning on screen aesthetically and rhetorically capture the interdependent process of working together to create access in dialogue.

An analysis of interdependence in these two characters’ relationship reflects key points from the opening chapters of this book, including how “we all rely on other human beings in various ways through different relationalities” (Gonzales & Butler, 2020) and how interdependence involves “our commitment to collective access—i.e., access not just for [other individuals] alone, or for us alone, but for all of us together” (Price & Kerschbaum, 2016, p. 28). Through what Kerschbaum (2014) calls answerable engagement, characters and we recognize how we are all “accountable to one another and willing to step forward not only to acknowledge but also to engage difference” (p. 119).

By studying scenes between Goodwin and Wilder in progression together and recognizing these experiences in our own lives, a reality is demonstrated: our screens are replications of our lives and authentic representation of communication—including the challenges—can intensify our appreciation for how each one of us works together to support each other and our shared commitment to learning from each other across differences.

FORMING CONNECTIONS AND INTERDEPENDENCE

While Max and Elizabeth interact on a regular basis throughout the previous season, often with Ben interpreting, Episode 2 of Season 5 creates the first subtitled scene in which audiences begin to sense the connection being formed between Max and Elizabeth.

In this scene during “Hook, Line, and Sinker” (Ginsburg et al. & Denysenko, 2022), Max comes to Elizabeth’s office committed to addressing her directly and meaningfully. He starts to sign without voice, and subtitles appear on screen so that sighted viewers can access his signs (Figures 5.1 and 5.2). He starts signing, “I am…,” and then immediately mis-signs one word with the subtitles showing him signing “nf@z;v#n[e.” After that he signs, “we are…” and “football.” The subtitles appeal to viewers by making us sense Max’s earnestness as well as the humor that occurs when attempting to learn a new language.

Elizabeth, with the embodied knowledge of Deaf people who regularly use different strategies to communicate with hearing people, responds by writing on a sticky note, “Was that a haiku?” and showing the sticky note to Max with a smile.

Figure 5.1: Max’s miscommunication to Elizabeth embodied in garbled subtitles and remedied through writing in New Amsterdam

Figure 5.2: Max’s miscommunication to Elizabeth embodied in garbled subtitles and remedied through writing in New Amsterdam

Max verbally answers in the negative and Elizabeth laughs, as the closed captions show. After Elizabeth offers the pen and paper to Max for him to write, he declines, saying “I don’t want to use this,” wanting to make his signed message clear to her.

Trying again, his signs improve as the subtitles show. However, instead of signing, “football,” this time, he signs, “hamburger.” She explains his mistake to him and shows him the sign for FRIEND. The scene ends with both of them signing the word “friend” without captions or subtitles.

This is their first moment of direct connection, and the captions and subtitles reinforce audiences’ recognition of their interdependence as they communicate through spoken English, signs, and text that was literally written down.

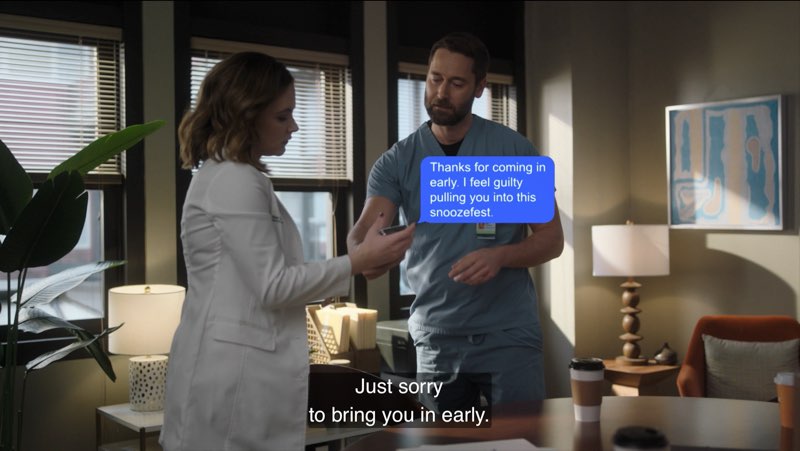

The next episode, “Big Day,” (Valdivia et al. & Carbonell, 2022) ends with a meaningful scene between Max and Elizabeth that shows yet another interdependent strategy that can be used to connect through visual text and multiple modes of communication. After a challenging day at work, Max and Elizabeth are seated outside the hospital at night. Despondent, Max uses his phone to write a message that he then shows to Elizabeth. While Max holds his phone for Elizabeth to read the message, the message appears as a blue bubble akin to a real text message in the space between their bodies.

Through this aesthetic and rhetorical integration (Figures 5.3 and 5.4), the visual text shows viewers not only the message being written and read, but also turns us into Elizabeth herself. Like her, we are reading the message, directly connected to Max, who is physically next to the phone.

Continuing the exchange, Elizabeth uses the same phone to write her response and shows Max. The proximity of this message in between Max’s face and the phone means that we are like Max reading the message and are like Elizabeth seeing Max’s facial reaction. Through this integration of the message, we directly connect with both characters and their despondence after a rough day at work.

Figure 5.3: Text message bubbles that show how Max and Elizabeth write and read their messages to each other in real time

Figure 5.4: Text message bubbles that show how Max and Elizabeth write and read their messages to each other in real time

After this exchange, Elizabeth signs to Max that he should go and hug his daughter. He copies her signs and speaks, “Go?” and “hug,” and then turns off his voice and emulates her in fingerspelling his daughter’s name as the letters appear one by one in open subtitles on screen. This joint spelling of Luna connects them and viewers as well.

When evaluating any captioned or subtitled scene, the choices that writers and creators may have made when developing a scene should also be dissected. The fourth episode of the fifth season of New Amsterdam, “Heal Thyself,” (Foster et al. & Martin, 2022) included a storyline in which Elizabeth required surgery that would prevent her from operating for several weeks, yet she miraculously was recovered by the next episode and this storyline was not mentioned again. Throughout the episode, she understandably was resistant to having the surgery because of the temporary loss of use of her hands. After she realizes the need for the surgery sooner rather than later, the episode ends with her in her hospital bed post-surgery, Max by her side.

In his commitment to making communication accessible for Elizabeth, Max has created a form of a communication board with words on the whiteboard. Max signs, with subtitles showing his steady pace as he commits to signing clearly, “I… will… be… your… hands. If you want.” The scene, and episode, ends with Max seated next to Elizabeth, placing his hand on her shoulder. The subtitles in this scene embody Max’s earnest commitment to ensuring communication access for Elizabeth and his growing use of ASL without spoken English. In addition to this visualization of interdependence, the final frame shows Max’s hand literally on Elizabeth as their connection becomes ever more direct.

While previous episodes ended with conversations between Max and Elizabeth, the sixth episode, “Give Me a Sign” (Legere et al. & Lee, 2022), opens with Max and Elizabeth running together on city streets. Elizabeth occasionally signs some phrases with no subtitles. The focus is not on the actual conversation but rather, the connection between the two as they run and music plays in the background. When they stop at a riverfront spot, Max signs, “You okay?” with subtitles as they catch their breath.

Elizabeth replies, “Yeah.” Then she adds, “You?” The second word shows up next to the first word to become one, as opposed to two separate thoughts. She starts running, and they continue to run into the next scene.

In contrast to their first dialogue in this episode (which includes only subtitles), the final scene of this episode shows how the layers of captions and subtitles can create different meanings for viewers who might be reading the closed captions and viewers who might have the closed captions turned off.

As part of the storyline for this episode Max and others are in the middle of painting a street crosswalk, and Elizabeth shows up to contribute. She signs, “How can I help?” Max, who is holding paint rollers, speaks since his hands are occupied. His spoken statements show up as captions: “You can help…” “there.” He then asks, “Shall we?”

She signs, “After you.” For viewers who have the closed captions on, the subtitles appear above the closed captions that are still on the screen for “Shall we?” This juxtaposition creates different meanings for different viewers, since those who are reading the closed captions will see the two words side by side just as the two of them are facing each other side by side.

At the same time, the layering of spoken English (with and without closed captions) and subtitled ASL shows that it is possible to connect through multiple languages. This connection is reflected throughout this episode when Max and Elizabeth’s colleague, Iggy, a psychiatrist, treats a deaf child who has experienced language deprivation syndrome, introduces Elizabeth as a successful deaf surgeon to the child’s parents. Iggy also provides them with resources for bilingual (ASL-English) education. Iggy advises the parents, “Unfortunately, medicine—our world—is still very much filtered through an able-bodied perspective.” This articulates the value of appreciating different embodiments and the intrinsic need for communication and language that we have.

VISUAL, TEXTUAL, EMBODIED CONNECTIONS

As the season progresses, the show relatively realistically represents the time that it takes to learn a new language as Max works steadily to communicate through ASL. In Max and Elizabeth’s first scene together in Episode 8, “All the World’s a Stage…” (Palmer et al. & Leiterman, 2022), Max enters Elizabeth’s office with coffee for both of them—but she also has two cups of coffee. He speaks and signs, “Great minds,” with closed captions representing his speech. Elizabeth signs, “Think alike,” with subtitles showing her signs (Figures 5.5 and 5.6).

Figure 5.5: Closed captions showing what Max speaks, and open subtitles showing how Elizabeth finishes his thought through ASL

Figure 5.6: Closed captions showing what Max speaks, and open subtitles showing how Elizabeth finishes his thought through ASL

In true interdependent spirit, the two of them create complementary parts of a sentence through two languages, and audiences can engage with that through spoken English or closed captions and open subtitles.

Audiences once again join them in the use of different strategies and technologies to communicate, especially when Max then takes out his phone to text a more complicated message, and Elizabeth writes her own text back (Figures 5.7 and 5.8). Through this rhetorical and aesthetic design, audiences stay connected with the characters in proximity as blue bubbles for the texts appear next to their bodies.

Figure 5.7: Text message bubbles that show their conversation with each other, and closed captions showing what Max says at the same time

Figure 5.8: Text message bubbles that show their conversation with each other, and closed captions showing what Max says at the same time

Their direct connection is further sensed through the final part of this conversation as they switch to ASL, shown in subtitles. Lest audiences presume that they will always communicate directly with each other, a scene later in the same episode shows Ben interpreting for the two of them. If audiences wonder about the show’s intention for Max and Elizabeth, we start to get an answer in the final scene, a scene that encapsulates the multimodal nature of communication as well as the challenges of connecting with each other.

In this final scene, both are in Elizabeth’s office working on a medical document. After they complete the document, we see words typed out one by one on the computer screen: “And someone thought this would be a snoozefest.” Elizabeth and audiences then see the next word that Max types out: “Dinner?” The typed words essentially serve as captions.

Elizabeth signs, “Like a date,” shown in subtitles. However, Max does not understand, so she types it out for him and us: “Like a date?”

He reads the screen, and utters, “Oh. Uh…,” then looks at her directly and speaks, “Yeah, like a date.”

She signs back, “No.”

To understand why she declines requires waiting until the next episode, but this scene shows several modes of communication in the same space, including text on a computer screen that characters and viewers are shown at the same time. The text on a computer screen becomes captions and reflects the strategies used in real life to connect with each other through embodied and technological modes.

The challenges of forming connections with others and the value of working to understand each other are sensed in the ninth episode, which is called “The Empty Spaces” for a reason that soon becomes apparent. Elizabeth and Max’s first scene together finds them in a hospital elevator with subtitles showing Max signing how he learned “I am sorry” in his ASL class. It seems like he is making progress until he signs, “I made things very… puppet.”

She smiles and tells him it’s fine and that she’s glad that he is learning ASL. Viewers see her meaning through the subtitles, but he is still learning and does not capture her meaning.

Figure 5.9: Text message bubbles that show how they work to connect through the phone

Figure 5.10: Text message bubbles that show how they work to connect through the phone

![Max and Elizabeth are both holding a phone and each other's hands. The phone screen shows a text message conversation with blue and gray bubbles. A closed caption at the bottom of the screen reads, "[laughs]"](images/newamsterdams5ep9_3_laughs-2.jpg)

Figure 5.11: Text message bubbles that show how they work to connect through the phone

She takes out her phone and they text back and forth, as shown in Figures 5.9 and 5.10. The third screen capture in this sequence (Figure 5.11) shows their hands together on her phone.

However, while prior episodes showed them connecting through their phones, the feeling is different in this episode, as embodied in Elizabeth’s face when Max struggles to understand her signs. This lack of direct communication intensifies in the final scene of this episode when Elizabeth’s face shows clear disappointment when Max takes out his phone to write a message. Max’s text shows clearly that there is “something” between the two of them, and Elizabeth agrees, which leads Max to ask why she is pushing him away (Figure 5.12).

Figure 5.12: Max’s emotional question being shown through a text message bubble

In response, Elizabeth signs an eloquent message that is fully subtitled for audiences to access (thereby accomplishing the scene’s rhetorical purpose and appealing to audiences’ emotions). However, Max’s face clearly shows that he does not understand her signs and in essence misses her point.

When he asks her to slow down, she signs, “I don’t want to slow down for you. For anyone . . . I can’t be with someone who doesn’t know my language. I know you’re learning ASL.” She adds, “And it’s so endearing. And often hilarious.”

She explains, that, since he doesn’t fully know ASL, she can’t share everything she’s feeling with him in a way that he'll fully understand. She says that while she feels everything between them, she also feels “the empty spaces.” She doesn’t want to live and fall in love in “an empty space,” as shown in the following capture (Figure 5.13).

Figure 5.13: Elizabeth’s eloquent signed message being shown to audiences through subtitles

After that eloquently signed message, Max responds that he’s sorry but he didn’t get “all of that.” Elizabeth signs back, “I know.”

With that exchange, and lack of communication, audiences access Elizabeth’s embodied rhetorics. We sense her powerfully signed message and what Elizabeth is feeling: how Max did not understand what she said and what we understood. We are one with her as we sense the missed connection, the empty space where participants in a dialogue cannot access each other’s meaning. The open subtitles continue to reflect an awareness of the multiple ways that audiences could engage with Elizabeth’s emotions: those who don’t know ASL can access her language through subtitles and through her facial expressions and embodied performance, while those who know ASL could access the language through watching her directly. Yet all can sense her eloquence and desire for someone to fully know her.

Elizabeth’s emotional appeal at the end of the ninth episode is an effective dramatic set-up for a full exploration of her feelings about her role at New Amsterdam in the subsequent episode. The 10th episode, “Don’t Do This for Me” (Foster et al. & Voegeli, 2022), begins in Max’s office as he engages in a signed and spoken conversation with his ASL instructor, who congratulates him on his progress; she then asks him where he got his “motivation.”

Not coincidentally, as soon as she asks that question, Elizabeth enters the office and, with firm conviction, signs to Max, telling him, “Don’t do this for me.” She leaves without giving him the chance to respond, and as she departs, audiences are given a moment of levity. Max’s ASL instructor asks him, “Did you get that?” In response, Max signs and speaks his answer, “Oh, yeah. No, I got that one. Crystal clear.”

With this opening scene, we sense the conflict, which prepares us for the main storyline of this episode for Elizabeth. Her mentor from medical school, played by Marlee Matlin, is opening a new medical school for deaf people. She invites Elizabeth to teach there and become a mentor for the next generation of deaf doctors. Matlin’s character emphasizes that at the medical school, Elizabeth would be with other deaf individuals. Elizabeth deliberates this offer throughout the episode.

Midway through the episode, Elizabeth reaches out to Max from across a common area at the hospital and signs (with subtitles) asking to talk. Once they enter his office, Elizabeth begins with a professional stance as she signs with Ben voicing and informs Max that she is leaving. Max, in response, asks that they be alone.

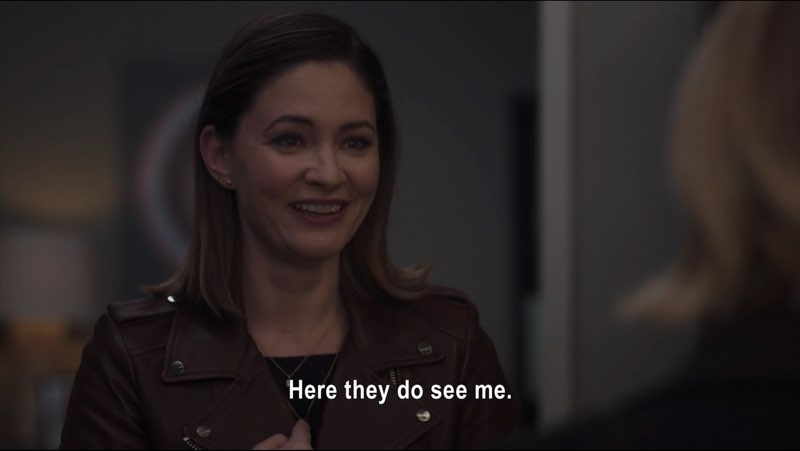

After Ben departs, Max signs to Elizabeth and asks her if this is really what she wants, and he emphasizes that he is asking about her (as opposed to what she thinks she should do). He adds that he’s not learning ASL “for you,” but “because of you.” He continues, “When our hospital interacts with you… we realize… what we thought were your limits… were actually our own.” He adds, “I see you.”

Through this scene, Max shows the value of differences and embodies access not as something for one individual, but rather as a process that everyone engages in to learn from each other, see each other, and grow as individuals in the interdependence process of connection (as shown in Figures 5.14 and 5.15).

Figure 5.14: Max and Elizabeth signing—with subtitles—to show that Elizabeth is seen at the hospital

Figure 5.15: Max and Elizabeth signing—with subtitles—to show that Elizabeth is seen at the hospital

By the end of the episode and their shift at the hospital, Elizabeth has made the decision to stay and informs her mentor, “Here they do see me.” She then catches up with Max as he starts to leave the hospital to tells him, “I’m staying.” She then asks him to take her home.

However, in a dramatic twist, Max hears—and the closed captions show—his ex-fiancé, Dr. Helen Sharpe talking on the television set in the hospital corridor about how she is back in New York City. The episode ends with this dramatic pause as audiences are left with the uncertainty of what will happen next.

SOMETHING REAL

Audiences continue to sense the duo’s connections, and missed connections, through a mix of technologies and modes. Light humor is created as it becomes clear that Ben, the interpreter, wants to avoid the awkward personal situation between Elizabeth and Max. In their first scene together in the antepenultimate episode, “Falling” (Mansour et al. & Horton, 2023), Max meets up with Elizabeth and Ben in a hospital corridor. Max asks Ben to stay and interpret because, as Max says verbally, “I’m just a little more clear when I’m not using the wrong words, or, uh, unintentionally swearing.” This indeed reflects a reality of multilingual communication as we all work hard to ensure that we express ourselves clearly through a different language, especially one that we are learning.

However, as Elizabeth has shown us throughout the last few episodes—particularly when showing how she does not want to fall in love in an empty space—she wants to communicate directly with Max. She asks Max to not “include Ben in our private conversations,” which Ben voices. Subtitles then appear when Elizabeth signs, “If there’s something you want to tell me, you say it,” as in, sign it. Ben departs and Max signs to Elizabeth about how his ex-girlfriend is not in his life anymore and that Elizabeth is. He asks her if that made sense and she shares her own story of avoiding an ex. It turns out that he was indeed clear. Through this subtitled conversation, they extend bridges to each other.

Later in the episode, Max and Elizabeth have a signed and subtitled conversation in which Max shows Elizabeth text messages from his ex-girlfriend asking to meet up. He tells Elizabeth that he is not going to see his ex-girlfriend, but she tells him to “look at her” and then decide what he really wants. The importance of looking for a sighted deaf person plays a part in this scene as we look at the phone to see what Max wants to show and as Elizabeth, looking directly at Max, asks him to look before he decides.

Max does go to the bar and looks at his ex-girlfriend and leaves without entering the bar. Instead, he goes to Elizabeth’s place and signs to her, with subtitles, that he has made a choice: her. The door closes behind them.

With Max and Elizabeth connecting at the end of the episode— with two more episodes to go in this drama series—we will end our analysis here; readers are encouraged to watch the season in its entirety and analyze the two characters’ interdependent communication practices.

Let us now reflect on the progression of Ryan Eggold and Sandra Mae Frank’s characters as visualized through captions, subtitles, and text on screen. The incorporation of multiple forms of written and textual words on screen signifies that space is being created for multiple modes of access in this show. Through the subtitles for ASL scenes, the characters articulate for themselves to portray their embodied experiences. With the mix of captions and subtitles, text messages, and other written text, multimodal/lingual/textual communication becomes accessible while reflecting the rhetorical and aesthetic principles of this hospital show on network television. Just as the characters show audience awareness in working through the challenging and rewarding process of attempting to understand each other, the series asks its audience to join these characters in their dramatic journey being pulled away from and toward each other.

Alongside their personal connections and increased number of subtitled lines, throughout these episodes, Max and Elizabeth continue to interact professionally around the hospital with Ben interpreting and closed captions. Through these mixed scenes, we navigate a multidimensional world of communication. There is no empty space between them as they come together through languages, modes, and means of access.

JUXTAPOSITION: ACCESSIBLE COMMUNICATION THROUGH WRITTEN TEXT

My video for this chapter shows several ways in which creators can apply an analysis of programs to the design of captioned and subtitled videos. As you play the video version of this chapter, consider strategies to make communication accessible through written text on screen.

In this video, I discuss and replicate communication strategies that Max and Elizabeth use with each other, specifically written text. When I discuss how Max may speak when he does not know the signs for words, the integral subtitles first appear in the space next to my face and then end with replications of closed captions at the bottom of the screen. This emulates how the show may switch to or from subtitles in the middle of a conversation when the characters change how they communicate.

I also recreate how Max and Elizabeth share text messages with each other when I show that the show replicates their text messages on screen in the space between their bodies so that audiences can read the message and see their reaction at the same time. In my case, I had consciously prepared for space in the center of the screen and used my hands to frame the center of the screen while moving from one side to the other of the screen. That embodied performance draws attention to the center of the screen where the message appears for audiences.

By further detailing the different strategies that Max and Elizabeth use—including text messages, I hope to show creators how we can open ourselves up to imagining different ways to depict text on screen. From pedagogical to social media contexts, creators could incorporate text messages and handwritten messages more intentionally on screen to embody contemporary digital communication practices when sharing content online. Foregrounding these strategies here is one way of showing the potential for enhancing the accessibility of our videos through text in various forms, just as Max and Elizabeth use various forms.

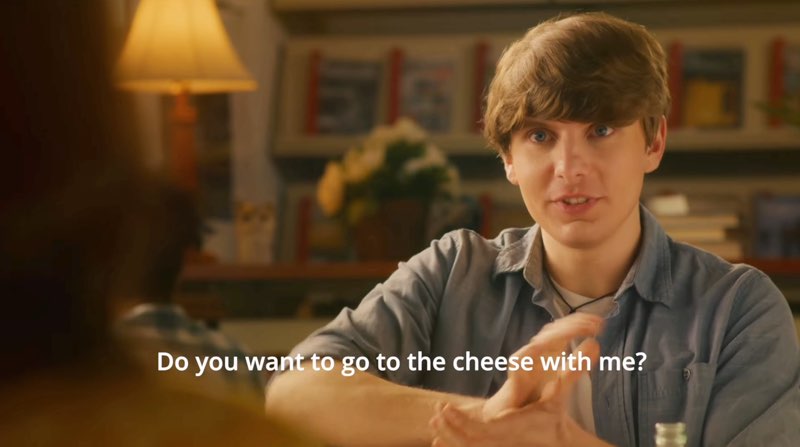

CROSS-CULTURAL COMMUNICATION: SAY CHEESE

The interdependence of the two characters in New Amsterdam are dramatic portrayals of how we each collaborate with others across languages and modes to connect, including with audiences. This interdependence is further affirmed in a student production from my university, Rochester Institute of Technology, Say Cheese, that teaches audiences some new signs. I had no role in the creation of the short film and serve here as a celebrant of this interdisciplinary collaboration between students from different backgrounds: Two film and animation students, Gabriel Ponte-Fleary and Anna McClanahan, produced and directed a short film that won the Coca-Cola Refreshing Films program’s grand prize in 2022 (Swartzenberg, 2022); the film was shown in theaters around the country and online.

In published interviews, these students (one hearing and one Deaf) and their fine arts and theater professors and members of the production celebrate the cross-cultural collaboration, a collaboration that grew out of our institution’s rich mix of DHH and hearing students from a wide range of backgrounds (Kiley, 2022; Swartzenberg, 2022). Ponte-Fleary states, “We wanted to show that any kind of relationship between deaf and hearing individuals is possible.” Furthermore, McClanahan says, “The human connection conveyed in the film is applicable to everyone’s lives and relationships.” They are shown in the preliminary introduction to the film, as shown in the following screenshot (Figure 5.16) as Ponte-Fleary signs the word “film.”

Figure 5.16: Film and animation students who produced and directed a short film

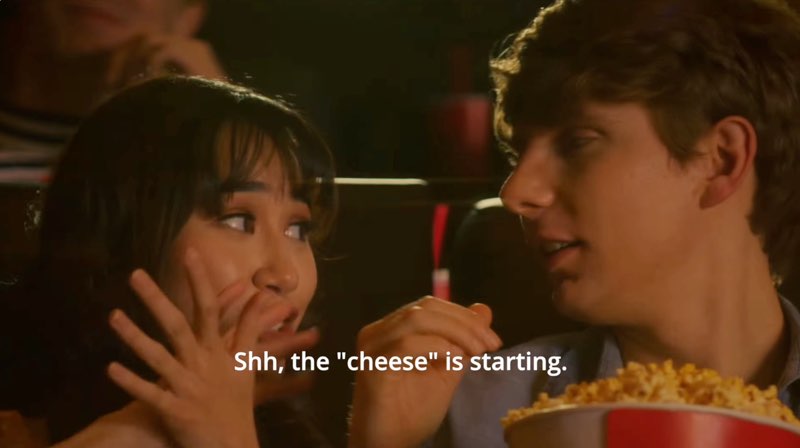

The sweet and lighthearted film shows a hearing male character attempting to ask a Deaf student out in ASL. The subtitles show him signing the word “cheese” instead of “film,” which is easy to do since the two words are similar in ASL, as shown in the following screen captures (Figures 5.17 and 5.18).

Figure 5.17: Miscommunication due to the similarity between the sign for cheese and the sign for movie

Figure 5.18: Miscommunication due to the similarity between the sign for cheese and the sign for movie

He follows up with fingerspelling the word M-O-V-I-E (Figures 5.19 and 5.20) and she laughs. They then go to the movie theater. In the clip’s crescendo, she interrupts his signs, saying “Shh, the ‘cheese’ is starting.”

Figure 5.19: Finding ways to go beyond miscommunication and to connect

Figure 5.20: Finding ways to go beyond miscommunication and to connect

Through this conversation, and the real-world collaboration that made this production possible, viewers can be inspired by the uplifting sensation of connecting across cultures and languages. “Mistakes” are a part of this interdependent process of learning from each other and extending connections across differences, especially as this film succeeds in teaching mainstream audiences the signs for cheese and movie.

INTERDEPENDENCE AND ACCESS

These students’ and characters’ interdependence and commitment to communication access replicates real-world conversations in which all dialogic participants contribute to access. Their strategies are strategies that ordinary people would use in real life when communicating with each other through different technologies and media in the collaborative process of ensuring mutual understanding. Just think of how many web conferencing meetings there have been with participants using the text chat feature as a core component of or complement to the video conversation itself, not to mention live captions. How many times have participants used the text chat to ask for clarification or to follow up on moments that might have been missed or lost in transmission? These are moments of access through visual text, and we can further our commitment through collaborative projects and compositions.

The multi-textual nature of New Amsterdam and its dedicated portrayal of characters who learn to open themselves up to each other through all means of connection embodies the value of captions and subtitles and visual text as means of direct connection and interdependence. Access is not for one side of the conversation; access is because of everyone in the dialogue, from creators to actors and characters to audiences, as we all navigate access as a work-in-progress and an extension between ourselves and those we interact with.