To further expand a space for differences in our compositions, this chapter immerses us into several spaces in which DHH, hearing, and disabled characters communicate with each other and with us, the audience, through integral captions and subtitles that appear in predominantly closed-captioned productions. The integration of captions and subtitles in hearing media represents the benefits of designing a space for different embodiments, including Born This Way Presents: Deaf Out Loud, Crip Camp: A Disability Revolution, and The Company You Keep. Through the embodied multimodal approach, we can explore how the languages and identities of real individuals and characters are made accessible through integral captions and subtitles. Most of all, the design of the captions and subtitles underscores the value of communicating and connecting across differences.

BORN THIS WAY PRESENTS: DEAF OUT LOUD—DEAF AND HEARING WORLDS TOGETHER

In 2018, A&E TV aired a documentary that was executive produced by Marlee Matlin, an Academy Award winner and well-known Deaf actress. In this hour-long documentary, Born This Way Presents: Deaf Out Loud (Matlin, 2018), three families are spotlighted: the Mansfield family, the Garcia family, and the Posner family. The couples and their children represent a mix of D/deaf, hard-of-hearing, and hearing individuals who use different communication practices.

Throughout the hour, these couples share their lives and their values as they raise their children. The entire documentary is presented from their perspectives. Originally airing on mainstream television for general audiences, this documentary program is effective in showing the world the range of communication practices and identities in the deaf community, especially through the incorporation of a mix of closed captions and open subtitles. The open subtitles sometimes are placed at the bottom of the screen and other times placed next to individuals’ faces and upper bodies.

The documentary did not create open captions for every single line uttered in the show. The parents and children who speak appear on camera without open captions; their words are available via closed captions. The mix of spoken and signed conversations is captured in a conversation that Mick and Rachel have in a car about their child. Figure 4.1 shows Mick signing with open subtitles that appear next to him while closed captions at the bottom of the screen show the words that his wife Rachel speaks.

Figure 4.1: Open subtitles and closed captions in different places of the screen at the same time in Born this Way Presents: Deaf Out Loud

Instead of framing the lack of fully open captions as a limitation, we can recognize how the use of closed captions for the speakers seems to be more effective in showing viewers—both those reading the closed captions and those listening to the speech—the communication practices of these individuals. By incorporating open subtitles specifically for non-speaking ASL usage, the documentary effectively embodies the visual and multimodal power of signers with open subtitles. After all, if open captions and subtitles were included for every single speaker and signer, the visual power of the open subtitles would likely be diminished.

With closed captions used for speakers, the moments in which ASL users sign with open subtitles next to their bodies become ever more striking. It is the subtitled moments that draw in viewers’ eyes as we directly connect with the signers’ embodiment: their eyes, faces, and signs. The opening moments of the documentary bring viewers into Sheena McFeely and Manny Mansfield’s world, as shown in Figures 4.2 and 4.3. The subtitles appear near them at the bottom of the screen as they sign to each other while communicating in writing with a hearing individual.

Figure 4.2: Subtitles showing audiences what is being signed and what is being handwritten

Figure 4.3: Subtitles showing audiences what is being signed and what is being handwritten

The couple’s genuinely accessible and embodied rhetorics as ASL users are captured as the documentary brings us into their home environment with their two daughters: one Deaf and one hearing, both native ASL users. While some scenes incorporate subtitles at the bottom of the screen when they sign to each other, the most powerful moments come when the subtitles are integrated into the space around them, allowing viewers to see their signs and the words at the same time. Figures 4.4 and 4.5 show Sheena and Manny working with their daughters on math and language activities as subtitles are integrated effectively near Manny.

Figure 4.4: Subtitles that stay near a father and daughter having a signed conversation

Figure 4.5: Subtitles that stay near a father and daughter having a signed conversation

Through this strategic integration, we can pay attention to this family’s communication and connection with each other. The integral subtitles further reinforce the family dynamics in this home where ASL is the primary language.

At another point in the documentary, we are brought to Paco and April Garcia in their own kitchen as they sign to each other with subtitles appearing next to them. When April speaks to her son, closed captions are used (if you have them on), which shows caption readers that she is speaking. The strategic design of captions and subtitles (Figures 4.6 and 4.7) shows awareness of the different hearing levels of audiences and provides multiple ways of engaging with the different modes of communication and identities on screen.

Figure 4.6: Subtitles for ASL and closed captions for spoken English in this family’s home

Figure 4.7: Subtitles for ASL and closed captions for spoken English in this family’s home

The subtitles are most effective when they appear close to signers. We are later shown the Garcia family at their son’s potential new school, and open subtitles appear between the signers’ bodies, maintaining our eye contact with their signed conversation (Figures 4.8 and 4.9).

Figure 4.8: Subtitles between bodies in a signed conversation

Figure 4.9: Subtitles between bodies in a signed conversation

Interposed with these real-life moments are narrative stages in which each parent individually or as a couple addresses the camera directly against an entirely white background. For those who sign, sometimes their signs are voice-interpreted, with closed captions showing that an interpreter is voicing for them.

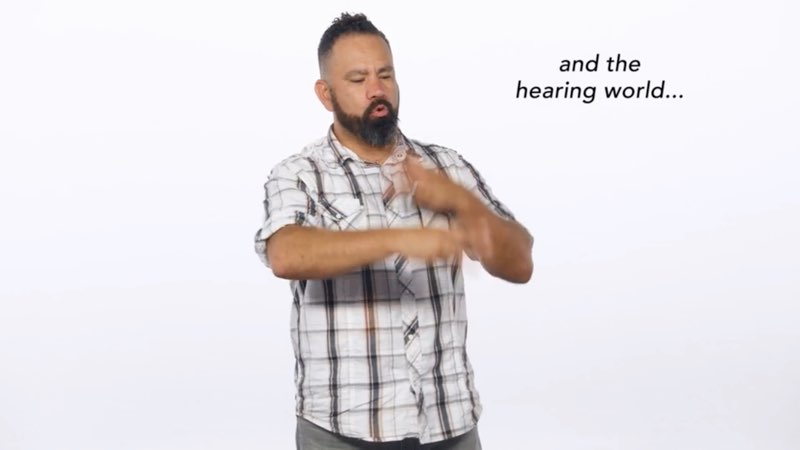

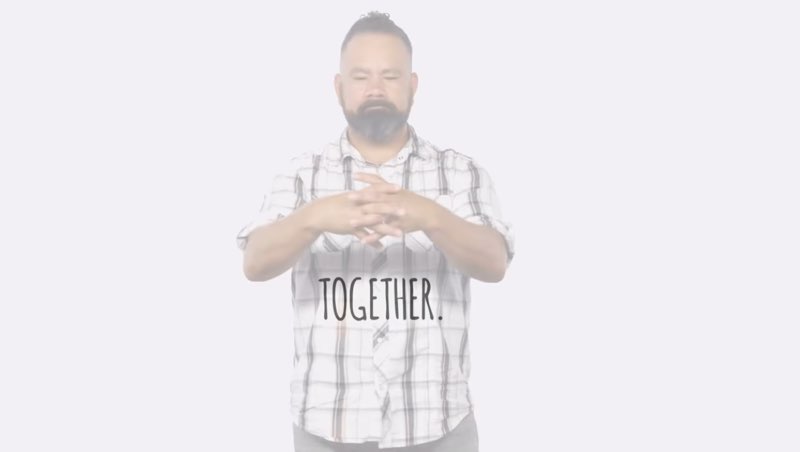

At other times, open subtitles are integrated next to them in proximity to their eyes and signs. The open subtitles appear striking clear against the white background, as shown in the following captures (Figures 4.10, 4.11, and 4.12).

Figure 4.10: Strategic placement of subtitles in different spaces of the screen to embody meaning

Figure 4.11: Strategic placement of subtitles in different spaces of the screen to embody meaning

Figure 4.12: Strategic placement of subtitles in different spaces of the screen to embody meaning

Viewed through the embodied multimodal approach, the holistic documentary creates space for multiple styles of captions and subtitles and modes of access. Each style embodies the experiences and multimodal and multilingual communication practices of these DHH individuals while reflecting effective rhetorical and aesthetic principles of the documentary style and demonstrating awareness of the different ways that DHH and hearing audiences would engage with the program.

Here, I am reminded of Brueggemann’s (2009, 2013) concept of “betweenity,” particularly how people with different degrees of hearing loss may identify in different ways in the spaces between capitalized Deaf, lowercase deaf, and other aspects of our identities. While “attending to the value of being between worlds, words, languages, cultures even as we can be contained in each one” (Brueggemann, 2009, p. 24), we can, like Brueggemann, explore opportunities for better understanding culture, identity, and language across differences. The captions and subtitles in Born This Way Presents: Deaf Out Loud create paths towards deeper appreciation of commonalities and differences in communication—and especially how we can make the spaces between us more accessible.

While the televised documentary used a mix of captions and subtitle styles, the online trailer (McFeely, 2018) that promoted the show embedded open, large, and stylized captions and subtitles throughout the entire trailer, including open captions for spoken English and for signs. These are shown in the following screenshots of the trailer (Figures 4.13, 4.14, and 4.15).

Figure 4.13: Strategic placement of larger and more visual subtitles for a trailer promoting Born this Way Presents: Deaf Out Loud

Figure 4.14: Strategic placement of larger and more visual subtitles for a trailer promoting Born this Way Presents: Deaf Out Loud

Figure 4.15: Strategic placement of larger and more visual subtitles for a trailer promoting Born this Way Presents: Deaf Out Loud

The design of the large captions and subtitles in the online trailer reflects the visual nature of DHH experiences while embodying the accentuated visual nature of online media communication, effectively appealing to the viewer who might be watching on a mobile device regardless of hearing level.

By integrating stylized captions and subtitles, the trailer embodies the spirit of the documentary and its message to audiences: the value and diversity of being DHH with different communication practices and the power that comes when bringing DHH and hearing worlds together.

JUXTAPOSITION: CAPTIONING AND SUBTITLING DIFFERENT EMBODIED RHETORICS

With appreciation of the many ways that DHH and hearing people communicate, I created this book and my videos to celebrate the potential for different subtitling and captioning approaches while highlighting the power of integral captions and subtitles. My video for this chapter in particular foregrounds how we can design words on screen to create access to different communication practices. I encourage you to keep the value of different communication practices in mind as you play the video.

In this video, I discuss how Born This Way Presents: Deaf Out Loud uses different captioning and subtitling styles when D/deaf, hard-of-hearing, and hearing individuals sign and/or speak on screen. I integrate different styles of captions and subtitles, including integral subtitles near my face or upper body as well as replications of closed captions in front of me near the bottom of the screen. With each line, I move my signs closer to where the text appears on screen, as by when I sign near the captions that appear near the bottom of the screen. In doing so, I guide the viewer’s gaze to the correct area of the screen to pay attention to and I reinforce my message about the value of communication access across modes.

In this case, I integrate subtitles into the space around me to embody my own practices as a Deaf scholar, but different creators who design videos certainly can create captions or subtitles that embody their own multimodal and multilingual practices, including when moving between languages or modes of communication. This multimodal movement will intensify throughout the next few chapters of this book as we are inspired by programs with a variety of captions and subtitles.

CRIP CAMP: A DISABILITY REVOLUTION—ACCESSING DIFFERENCES

Just as Deaf Out Loud embodies the value of being Deaf, deaf, and hard-of-hearing and communicating through multiple modes, Crip Camp: A Disability Revolution (Lebrecht & Newnham, 2020) is a direct argument for the power that comes when people with disabilities connect and advocate for disability rights and transformation in society. The documentary, released by Netflix in 2020, centers on interviews with individuals who became central in the Disability Rights Movement during the 1970s.

While Crip Camp does not focus on those who advocated for closed captions, the advocates’ work led to laws requiring closed captions. In this section, however, I want to focus on several moments in the documentary that integrated written text on screen to make individuals’ even more messages accessible to audiences.

In this documentary, Denise Jacobson and Neil Jacobson are individuals with cerebral palsy who are fierce advocates for disability rights. Figures 4.16 and 4.17 show closed captions at the top of the screen in brackets indicating who is speaking. Along the side of the screen, captions are integrated to show sighted viewers Denise’s words in textual form.

![Denise is moving a motorized wheelchair through the woods on an autumn day with leaves on the ground. Closed captions appear at the top reading, "[Denise speaking]" while open captions appear to our left near her that read, "If I close."](images/cripcamp_ificlose1.jpg)

Figure 4.16: Open captions showing Denise’s spoken English in textual form with closed captions showing that she is speaking

![Denise is moving her motorized wheelchair through woods on an autumn day with leaves on the ground. Closed captions appear at the top of the screen reading, "[Denise speaking]" while open captions appear to our left near her that read, "If I close my eyes."](images/cripcamp_ificlosemyeyes2.jpg)

Figure 4.17: Open captions showing Denise’s spoken English in textual form with closed captions showing that she is speaking

The captions are synchronized with her speech to make her message accessible to audiences. Figures 4.18 and 4.19 show how, as Denise shares her story on camera, open captions appear as large, synchronized words and phrases in temporal pacing with her speech. They are written across the screen next to her and also appear next to key images in the historical footage at other moments in the documentary.

Figure 4.18: Open captions appearing word by word in temporal pacing with Denise’s speech

Figure 4.19: Open captions appearing word by word in temporal pacing with Denise’s speech

To emphasize, in this documentary about disability rights and access, open captions are integrated in ways that embody her message and the value of access for audiences. This metaphorically echoes Speechless’ integration of captions for a range of audiences. Juxtaposed side-by-side, these examples demonstrate the power of visual text in multimodal expression and connecting across differences to access each other.

THE COMPANY YOU KEEP: HEARING AND DEAF SPACE

While the documentaries Deaf Out Loud and Crip Camp integrate captions and subtitles in ways that embody the value of multimodal access across differences, mainstream television programs can integrate captions and subtitles in rhetorically and aesthetically effective ways to express their messages to general audiences while embodying the value of accessible multimodal communication.

A more recent example comes in the form of ABC’s The Company You Keep, which premiered in 2023. This network show with hearing characters features Milo Ventimiglia as the main male lead, Charlie Nicoletti (alongside the main female lead, a CIA agent played by Catherine Haena Kim), and Charlie’s affectionate family of con artists, including his parents and sister. The youngest member of his family is his niece, Ollie, played by Shaylee Mansfield (who previously appeared in Born this Way Presents: Deaf Out Loud and has advocated for captions on social media as a Deaf person).

Throughout the beginning of the pilot episode (Cohen et al. & Younger, 2023), viewers follow Charlie and the adult members of his family in their activities. We are immediately drawn to them, essentially rooting for these likable characters. As Charlie explains in a later episode, the family only targets people who deserve to be conned.

Midway through the pilot episode, the camera brings us into his family’s bar where several members of his family are present. While the characters have spoken in the entire episode up to this moment (with closed captions), the camera now shows two individuals who we soon come to understand are Charlie’s niece, Ollie, and Charlie’s father/Ollie’s grandfather, Leo. This scene is remarkable for its natural integration of the Deaf character and subtitles in ways that quickly draw viewers into the everyday life of this family. We see the characters sign to each other with subtitles integrated into the space next to their faces and between them. The design effectively connects them with each other and viewers with performers, instilling in all of us the strong sense of love that thrives in this family.

Making this introduction to Ollie even more salient is the topic of conversation as Leo and Ollie discuss magic tricks and Ollie makes a point of stating, “I can see the card in your hand.” Viewers likewise see her hands, which move right next to the subtitles—and we continue to see the hands of signers throughout this scene, as shown Figures 4.20 and 4.21.

![Ollie is seated at a table in a bar and signing. Open subtitles appear next to her reading, "I can see the card in your hand, Nanu." Closed captions appear at the bottom that read, "[no audible dialogue]."](images/tcyk_ep1_1_icansee.jpg)

Figure 4.20: Subtitles in The Company You Keep appearing next to Ollie and Leo as they sign, with closed captions showing that there is no audible dialogue

![Leo is seated at a table in a bar and signing. Open subtitles appear next to him: "It's magic." Closed captions appear at the bottom and read, "[no audible dialogue]."](images/tcyk_ep1_2_itsmagic.jpg)

Figure 4.21: Subtitles in The Company You Keep appearing next to Ollie and Leo as they sign, with closed captions showing that there is no audible dialogue

Accessible multimodal communication intensifies when Charlie enters the bar with an urgent situation that moves the story forward, and we are shown the larger scene. Ollie’s mother, Birdie, is at the bar and wants to get Ollie’s attention. Leo supports that connection by drawing Ollie’s attention to her mother.

Before Ollie leaves the area, she faces Charlie and signs to him with subtitles integrated in the space next to her, as shown in Figure 4.22.

Figure 4.22: Subtitles that appear right next to Ollie as she addresses her uncle

Charlie, who viewers up to this point did not know could sign, then signs back. The young girl then leaves the room, and the adults discuss the urgent situation in spoken English, and the episode proceeds with no mention of ASL or Deaf people, which further intensifies the integration of Deaf people as a natural component of their lives. Instead of artificially writing a forced comment about Ollie being Deaf or about ASL in the script to try to introduce her identity to hearing viewers, this show integrates subtitles and invites audiences into this family’s accessible multimodal world of communication.

The integral subtitles strengthen audiences’ connection with them through the design of space for subtitles that rhetorically and aesthetically enhance visual and multimodal access to their conversations and the embodied rhetorics of this multigenerational family that signs. This invitation appeals to viewers who would ideally return for the episodes that follow this pilot.

Returning to This Space

Viewers meet Ollie again in several scenes throughout the season’s 10-episode run. The two episodes that follow the pilot integrate subtitled scenes seamlessly as audiences are welcomed into these adult characters’ everyday lives as hearing members of a family that has a Deaf child. The design and placement of subtitles alongside their bodies stitches these familial scenes into the fabric of the show.

The visual integration of subtitles in the space of the screen in the pilot episode makes more sense as the second episode (Cohen et al. & Mock, 2023) opens with the Nicoletti family pulling off a con; as each individual works from a different angle, highly stylized split screens and intercuts show viewers several characters at the same time within the same frame from different areas of the room and building. This visualization continues throughout the subsequent episodes as they carry out different cons. Likewise, when Charlie receives and sends text messages in this and later episodes, text message bubbles appear on the screen next to him.

The stylized visuals lead to only one instance of integrating subtitles right next to a signing character’s face in the second episode—but this design is subtle and effective. At this point, the Nicoletti family are in debt to another crime family, and a leading member of the other crime family, Daphne, pays an ominous visit to their bar.

After verbally interacting with Birdie at the bar, Daphne silently signs, with integral subtitles appearing right next to her stern, immobile face and intense eye gaze, “Say hi to your daughter.” The threat is immediately clear, as reinforced by the integration of the words right next to Daphne’s facial expression, which enables sighted viewers to see word and intention at the same time (Figure 4.23).

Figure 4.23: Subtitles that stay near a threatening sign of greeting

After that threat, to which Birdie’s facial expression clearly shows her emotional response, Charlie comes over and speaks, “Sign language. That’s not necessary.” Daphne responds, “Well, I just wanted to make sure I was being understood.” Her intentions have indeed been understood more powerfully than they would have been through speech.

Importantly, Ollie is not portrayed as someone who needs help, and she claims her agency throughout this series. The next time Daphne enters the bar in the following episode, Ollie tricks Daphne by pretending to compliment her purse—with subtitles integrated next to her—while sneaking a tracking device into Daphne’s purse, proving to us that Ollie is fully capable of sleights of hand and defending her family.

Stitching a Circle of Connections

While Ollie appeared briefly in the second episode, her increased presence in the third episode (Cohen et al. & Straiton, 2023) leads to several scenes in which subtitles are integrated effectively around the space of the screen next to various characters’ embodied language. This episode proves that it is rhetorically and aesthetically effective to design a space for captions and subtitles in extended conversations with multiple performers. Through these scenes, the subtitles stitch together characters—and these scenes are in turn weaved seamlessly into the overall arc of the show itself.

Early in the second episode, Emma, the main female lead who is in a new relationship with Charlie, meets Ollie for the first time. She introduces herself using the signs that we have previously seen her practice with Charlie (Figure 4.24). The subtitles appear next to her, allowing the audience to read her words through embodied language and text while Ollie reads the words on her hands. (Later in the episode, Emma meets Ollie for the second time and introduces herself again with subtitles appearing in the same location next to her; this time her signs appear more fluently, as Ollie observes.) The contrast between Emma’s smiling greeting and Daphne’s unsmiling threat is apparent.

Figure 4.24: Subtitles that stay near a friendly sign of greeting

After Emma and Ollie meet for the first time, the following scene presents one of the most effective manifestations of the potential of integral captions and subtitles in stitching together characters with each other and with audiences as we are given the opportunity to experience this family’s natural form of embodied communication in the presence of Ollie. While most scenes of the series show the adults speaking, they—and subtitles—seamlessly slide to ASL when they are with the Deaf member of their family.

What makes this scene stand out is how an extended conversation occurs with multiple characters, including characters joining the circle, and subtitles are always integrated into the space next to them, heightening the visual access to their embodied meaning. Audiences are not drawn away from their signs to words at the bottom of the screen but can stay with eyes, faces, and body language alongside text. Bodies and words are read at the same time. This is not a silent scene as the hearing characters variously use a mix of signs and speech, including by only signing when addressing Ollie directly or by signing and speaking at the same time.

The scene begins with Charlie and his sister Birdie, Ollie’s mother, in their home verbally talking about their family’s situation. Ollie comes in, catches the last thing they said, and signs with subtitles appearing, and staying, next to her as she walks into the room. Charlie responds by explaining that it’s “grown-up stuff.”

Ollie reveals that Charlie and Emma are in a relationship, which prompts Birdie to make comments to her brother about his love life. The adult siblings reignite their spoken conversation—but by speaking without signing, they are preventing their Deaf family member from accessing this conversation. In response, Ollie thumps the table and calls them out for being “rude” (Figures 4.25 and 4.26).

Figure 4.25: Reinforcing the importance of accessible communication

Figure 4.26: Reinforcing the importance of accessible communication

Charlie immediately signs “Sorry,” and Birdie signs directly to Ollie explaining that Charlie doesn’t realize that his love life is a “liability” for the family. At this point in the conversation, the siblings sign back and forth to each other with subtitles appearing next to each individual, which proves that they recognize the importance of signing even when addressing each other directly, so that Ollie can access their dialogue.

The conversation continues and deepens in its multilayered stitching of meaning as the siblings’ parents enter the space. Leo catches the last thing that was said and asks what he missed. Ollie informs him, with subtitles appearing next to her, that Charlie has a girlfriend. Leo’s surprised response is embodied through his mix of ASL (with subtitles integrated next to him) and spoken English.

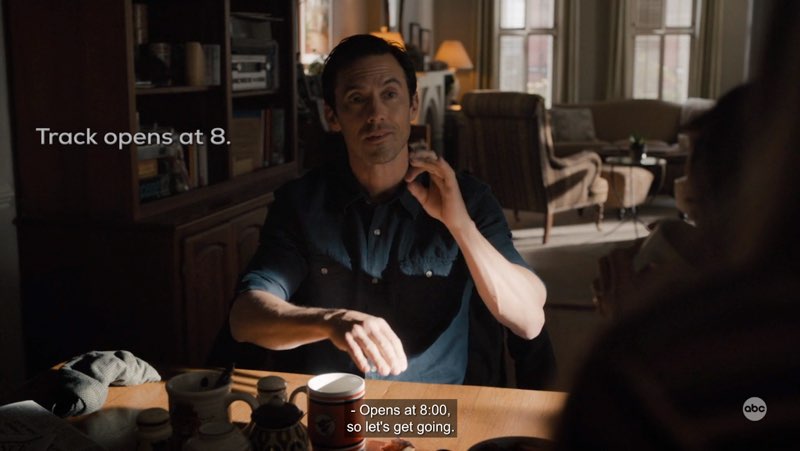

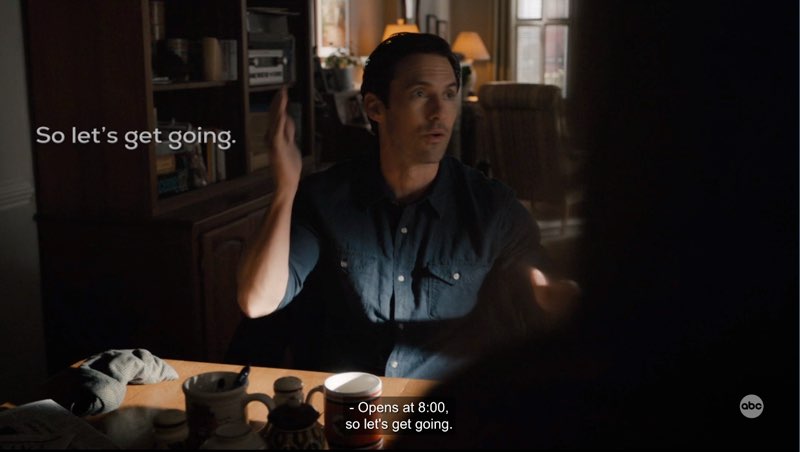

The simultaneous expression of integrally subtitled ASL and spoken English is continued in Charlie’s response as he changes the subject to remind them about their plans to go to the track (Figures 4.27 and 4.28)—and in Birdie’s signed, spoken, and subtitled apology for what she said.

Figure 4.27: Subtitles and closed captions at the same time for a message that is being simultaneously signed and spoken

Figure 4.28: Subtitles and closed captions at the same time for a message that is being simultaneously signed and spoken

This scene is a major demonstration of the affordances of integrating subtitles in extended multi-person conversations as audiences become part of the circle of bodies in interaction. In just this one extended family conversation, we are shown that space has been designed for captions and subtitles and multiple modes of access for Ollie and audiences and we sense the embodied rhetorics and experiences of this family of hearing and Deaf individuals as they communicate through multiple modes and languages. The rhetorical and aesthetic qualities of the scene are heightened, not detracted from, as the show shows awareness of the ways that audiences could engage with this kindhearted family in this scene and with their stimulating story in this series.

The seamless integration of subtitled scenes into the fabric of the show stitches together the Nicoletti family’s love for each other in their private family scenes with the dynamic exploits of these family members in the world. Throughout other scenes of the show, heightened visuals include text message bubbles on screen, tweets that appear as bubbles on screen, and—in this episode at a horse track—cash values that are visualized through green text on screen above the bodies of bettors and odds that are visualized through white text. Their multilingual conversations are a natural part of their lives and this show, a sense that is reinforced by the episode’s transition from the family conversation to the next scene: right after the family conversation, we join them at the horse track and begin with Ollie and her grandfather signing (with subtitles next to them), then we proceed with the main storyline in the hearing world.

Intentional Inaccessibility

The accessibility and interdependence of the Nicoletti family’s integrally subtitled conversations stands in contrast with exclusively spoken scenes, as in short scenes in later episodes. These short, subtitled scenes reinforce distance rather than connection.

The physical separation between speakers and subtitles exists with other spoken languages in this show. In one episode (Cohen et al. & Huertas, 2023a), Daphne, a leading member of a crime family, is with two male members of another crime family. The scene opens with the three of them speaking in English. At one moment, one of the two male characters adds a private comment to his uncle in Mandarin, with the closed captions saying “[speaks Mandarin].” When he speaks and when his uncle answers with a curt request to stop talking, subtitles appear at the bottom of the screen. After this brief exchange, they resume speaking in English with Daphne.

In another episode (Cohen et al. & Mastro, 2023b; Episode 6), Birdie is at a party in which the attendees listen to an opera singer and no subtitles appear to provide access to the language of the singer, reflecting the attendees’ lack of familiarity with the language. In a later episode (Cohen et al. & Mastro, 2023a; Episode 8), Emma, a CIA agent, is in disguise as a criminal meeting with another criminal. During this conversation in English at an outside table on a sidewalk, she momentarily speaks Korean on her phone. The subtitles are placed at the bottom of the screen closer to the characters’ feet under the table, a distance that reinforces the distance created by her conversation in Korean, which the other person is not meant to be able to access.

The traditional approach in these scenes contrasts with the integration of subtitles in signed scenes in other episodes. In these spoken scenes, the aural message is purposefully not meant to be understood by the other person in the space or the others in the space are clearly not fluent in the language. Conversely, the signed scenes reinforce a community of access—and communication access occurs through interdependence and multiple modes of engagement with each other.

The Tangible Nature of Familial Connections

Ollie remains a recurring character in several episodes, and when she does appear, it is in scenes that reinforce the family’s love for each other. Throughout the second half of the season, the familial connections amongst the Nicoletti are intensified through the integration of subtitles in the spaces they share.

The placement of subtitles shows us their eye gaze and embodied connections, shown in a pivotal episode that introduces us to Ollie’s father (Cohen et al. & Mastro 2023a). To help the family carry out an art con, Birdie reaches out to her ex-boyfriend, Simon, who she has not seen in eight years and who Ollie is not aware is her father. After the adults succeed in their mission, two back-to-back scenes with integral subtitles bring audiences into the emotions of these characters and their desire to connect with each other.

Near the end of the episode, Birdie, Charlie, and Simon are wrapping things up in the bar basement. Simon notices Ollie spying on them and recognizes her as his daughter right away. Simon signs, “Hi, I’m S-I-M-O-N,” as each letter appears one by one on screen with a hyphen in between reflecting his slow fingerspelling. This contrasts with Emma’s more fluid spelling of her name the first time she met Ollie. The subtitles stay by Simon’s hand, including as the camera switches to show us Charlie’s realization that Ollie is there. This allows viewers to see two things at the same time: Simon signing and Charlie seeing Ollie.

The adults’ concern is profound because up to this point, Ollie has not been in the basement, the place where they work on their cons, and Ollie has not been told that the adult family members are con artists. The concern becomes further evident when, after Ollie introduces herself to Simon, Birdie walks in the middle of the two physically severing their connection. As she signs to Ollie, her body and words block her and us from Simon.

Ollie then stomps off and Birdie pursues her, leaving the two men in the basement. Simon remarks on how beautiful his daughter is, and Charlie rebuts by emphasizing that Ollie is smart, too. Charlie asks Simon how long he’s been signing and Simon explains that he’s been taking classes online: “I’m clearly not fluent, but I’m working on it.” Audiences can recognize this through the subtitles that reflected his slow progression.

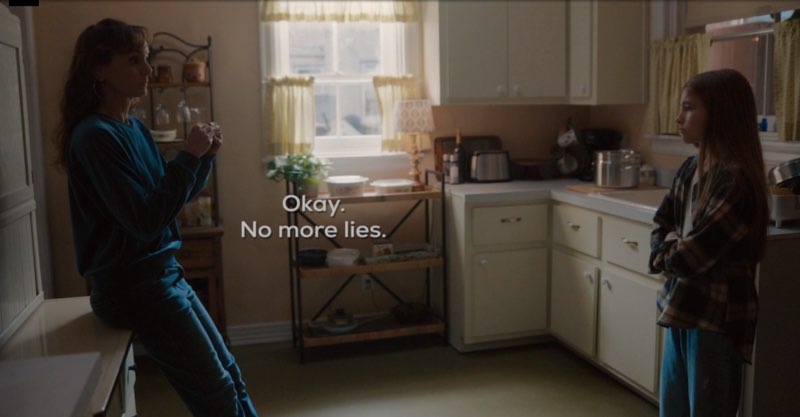

Although Birdie created a physical barrier in the basement, the next scene shows Ollie and her in the interdependent process of working together to be honest and trust each other. They are in their kitchen, engaging in an extended signed, silent, and subtitled conversation in which they maintain eye contact and clearly express their emotions and struggles. Their clear expression of their emotions is evident when Ollie asks her mother to be honest with her, and subtitles are integrated near her face just below the direction of her eye gaze as she looks at her mother (Figure 4.29).

Figure 4.29: Direct eye gaze being reinforced through the placement of subtitles

Through this mother and daughter’s commitment to open and honest communication with each other and subtitles that stay with each signer’s facial expressions and body language, we are shown how Birdie works to overcome her hesitancy and allow herself to answer Ollie’s questions directly with the truth about what the family does and how they, in Ollie’s words, steal from others.

Their connection continues as Birdie agrees to tell “no more lies” and Ollie asks if Simon is her father (Figures 4.30 and 4.31).

Figure 4.30: Eye contact between characters supported by the placement of subtitles

Figure 4.31: Eye contact between characters supported by the placement of subtitles

The placement of the subtitles maintains the connection between them and our connection with them as we sense their emotions. After asking about her father, Ollie closes her eyes momentarily and sighs deeply, which is sensed immediately thanks to the placement of the subtitles near her face.

Birdie succinctly nods, and Ollie then nods in recognition, then, with emotion evident on her face and hands as she prepares to ask her next question, we feel her emotions (Figure 4.32).

Figure 4.32: Ollie’s emotions being made apparent through the placement of her words next to her eyes

Birdie honestly tells her daughter that she’s not sure yet, and Ollie goes to her for a hug. After this extended process of reading their heartfelt emotions on their faces and the subtitles near their eyes and hands, we feel what they feel in this honest, touching conversation between mother and daughter.

Look at This

Subsequent episodes continue the meaningful integration of subtitles around characters in this close-knit family. Several scenes show the characters connecting with each other as subtitles are placed next to signers, including right in front of other characters in the scene. By placing subtitles in conversations amongst several characters, we are shown all members of this family and their connections with each other.

As an example, in one scene (Cohen et al. & Armaganian, 2023), Charlie and Birdie are next to each other in the bar, and Birdie signs to Ollie. We see Birdie and Charlie from Ollie’s perspective, and the subtitles are placed in front of Charlie, who is next to Birdie. This does not interfere with the composition because we read the words in front of Charlie’s body and Charlie likewise is reading Birdie’s signs. We essentially become Ollie as we connect with Birdie and Charlie at the same time. Beyond the storyline, the design of these subtitles shows us that subtitles can—when designed in rhetorically and aesthetically effective ways—theoretically be placed anywhere in a multimodal and multilingual conversation near, around, and in front of bodies in connection.

The connection between these family members reaches an especially aesthetic and poignant moment when subtitles stay on screen through two shots, tying together two signers through one message (Figures 4.33 and 4.34). This scene places Ollie and her father at one side of the bar counter with Birdie and Charlie at the other side of the bar counter. Ollie and her father head out together and Ollie waves goodbye to her mother using the ASL sign for “I love you,” waving her hand back and forth while signing “I love you.” In the next shot, Birdie signs “I love you” back. While these two moments are two separate shots or frames, the subtitles remain the exact same location on screen, magnetizing the two slices into one cohesive message of love and connection between mother and daughter.

Figure 4.33: The fixed location of “I love you” on screen across shots stitching together mother and daughter

Figure 4.34: The fixed location of “I love you” on screen across shots stitching together mother and daughter

This enduring message of love is written on screen across two shots. The metaphorical embrace of mother and daughter is intensified by the message’s near-central placement on screen. To experience the literal centrality of subtitles, we can end with the season’s final episode.

The analysis of The Company You Keep can conclude with one final subtitled moment during the show’s final episode (Cohen et al. & Huertas, 2023b). In this scene, Ollie has discovered a key document and shows the document to her mother. Subtitles are placed at the center of the screen underneath the document that Ollie holds (Figure 4.35). Sighted eyes remain at the center of the screen with the subtitles and the document.

Figure 4.35: “Look at this” at the center of the screen.

The group of words, “Look at this,” suggests where to place our eyes. This warrants a look at the possibilities for connecting through words and embodiments at the center of our conversations.

Through the many meaningfully subtitled scenes in The Company We Keep, viewers join the warm company of this loving family and recognize the effectiveness of the subtitles. With the embodied multimodal approach in mind, we can discern how the series reveals that space can certainly be designed for captions and subtitles and access. A major revelation of this show is its warm incorporation of subtitles in family conversations with multiple bodies, and the subtitles’ placement in front of, around, and next to bodies that are in close proximity to each other.

Through the design, the subtitles enhance visual and multiple modes of access to these conversations, including their conflicts and their connections. We directly experience their embodied rhetorics as they communicate through their eyes, smiles, and love for each other. They embody multimodal and multilingual communication and embody the series’ rhetorical and aesthetic qualities for us audience members. The dynamic visual nature of the show about pulling cons and winning people over shows awareness of how we audience members could engage with the characters and be charmed by the familial community they have formed. We ultimately connect with them and their world of communication across subtitles, signs, and sincerity.

INTEGRATING CAPTIONS AND SUBTITLES IN OUR LIVES

Throughout this chapter, we have been brought into different spaces where multiple identities and communication practices are embodied through integral captions and subtitles. Interactions and connections occur between real individuals, actors, and characters—and this extends the reality of our lives, as reflected in actress and advocate Mansfield’s creations on social media. Many of her videos on social media incorporate written text in apparent ways on screen to embody the value of captions, both when she actively calls for better access to captions and when she incorporates them naturally as necessary components of an accessible video.

While a review of the many social media videos that she has created and appeared in since she was very young is beyond the scope of this book, the videos she posted around the time that The Company You Keep aired on NBC reflect how captions and access are innate, intrinsic values in her life and culture and how captions and access should be valued by all in society. In a video posted on Instagram (Mansfield, 2023b), she shows viewers what it is like to be a Deaf actress and introduces viewers to different parts of the soundstage, including her trailer.

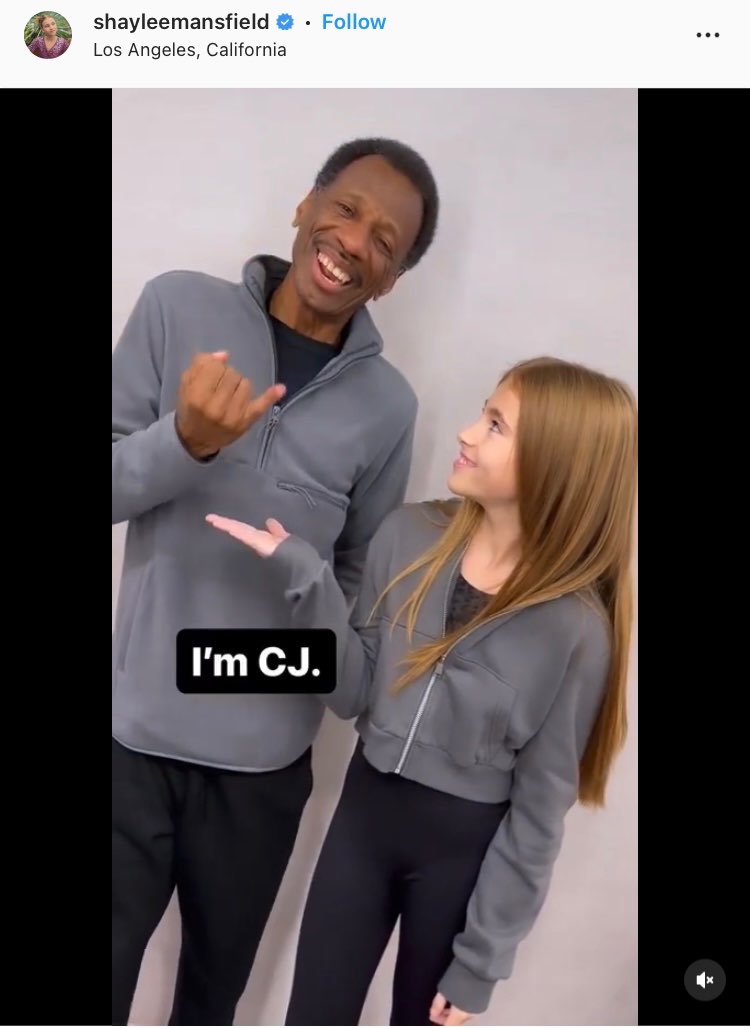

Through visual text embedded on screen, she shows viewers that interpreters are not only for her, but for all hearing individuals involved with the production as well. Most notably, she introduces CJ Jones, a Deaf actor and ASL consultant for the show (Figures 4.36 and 4.37).

Figure 4.36: Shaylee Mansfield and CJ Jones in an Instagram video with subtitles.

Figure 4.37: Shaylee Mansfield and CJ Jones in an Instagram video with subtitles.

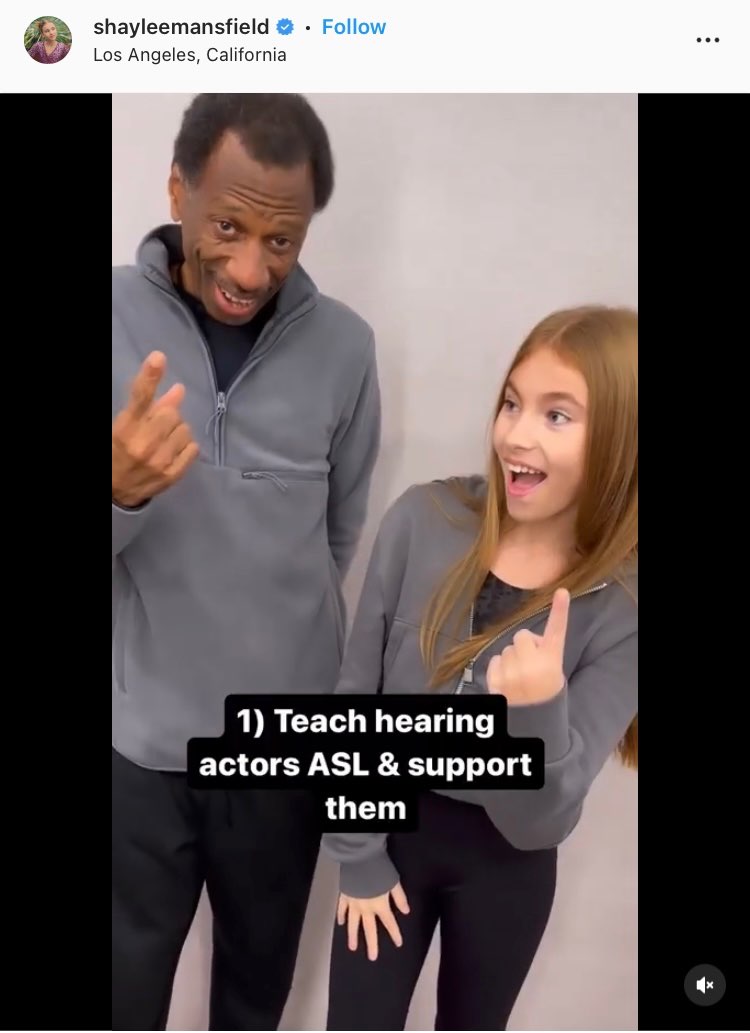

The video describes how CJ is serving as an ASL consultant for the show. They then list out numbers on their hands while captions on screen describe different aspects of his job, including teaching hearing actors ASL (Figures 4.38 and 4.39).

Figure 4.38: Shaylee Mansfield and CJ Jones explaining his job through words on screen.

Figure 4.39: Shaylee Mansfield and CJ Jones explaining his job through words on screen.

This part of Mansfield’s video gives viewers a backstage look at the world behind the show and those individuals who contribute to ensuring that ASL is represented authentically on screen. At the same time, the incorporation of visual text closer to the center of the screen—including subtitles for signs and captions for words that she does not sign—reinforces the value of designing a space for captions and subtitles on screen and connecting across cultures and languages in our lives.

INTEGRATING OUR WORLDS OF COMMUNICATION

The integral captions and subtitles in Deaf Out Loud, Crip Camp, and The Company You Keep reflect the design of variously shared spaces for embodied rhetorics and communication practices. These integrally captioned and subtitled programs draw audiences immediately into the lives of different individuals and embodiments, and in doing so, underscore how we all live in a world of differences and commonalities. As we express our embodiments, we can connect and access each other. Just like these media, video creators can continue to design a space for integral captions and subtitles that embody our identities and the value of accessible multimodal communication in our communities and shared world. At the same time, we can celebrate the affordances of closed captions and other strategies for connecting across differences.