This digital book is a visualization of captions and subtitles as the embodiment of accessible multimodal communication. I ask readers to envision words on screen in all their forms, from traditional sentences at the bottom of the screen to highly dynamic text that moves across the screen, and to expand the possibilities for incorporating captions and subtitles as central components of video analysis and design. The chapters of this book unpack examples of broadcast media, streaming media, and online content with traditional closed captions, multilingual subtitles, and varied approaches that coalesce into a shared experience: communicating and connecting across languages and modes to make meaning accessible.

Analyzing and designing captions for spoken English and subtitles for multiple languages reveals how creators can bridge communication styles as we express our multifaceted identities to audiences with different lived experiences and embodiments, or ways of experiencing the world through our bodies. We connect multiple modes of meaning (including sound, visuals, and gestures) through captions and subtitles and enrich our strategies for connecting with audiences across differences. And through this multimodal and multilingual process, we make our message accessible to our audiences.

Fostering these accessible and multimodal connections is indispensable in our multicultural and interconnected digital world of communication. To encourage scholars and creators to make captions and subtitles central in the analysis and design of on-screen media, including online media, I use the chapters of this book to examine effective examples of captioned and subtitled videos and to demonstrate the value of captions and subtitles as the embodiment of accessible multimodal communication. This introduction lays the groundwork for understanding varied types of captions and subtitles and the value of embodying accessible multimodal communication with words on screen.

To uncover how words on screen can enrich accessible multimodal communication practices, I previously wrote (2016, 2018b) about the vibrant visual lyrics of American Sign Language (ASL) music videos, videos in which signers perform songs side-by-side with dynamic visual text. Visual lyrics that move in rhythm with signs and sounds show how captions and subtitles can embody multimodal meaning, including the movement of bodies and signs—and these vivid examples show that we can create a space for the analysis and design of captions and subtitles. In this book, I go further in arguing that scholars and creators can analyze and design captions in all their forms, including as traditional lines of texts at the bottom of the screen, to embody the many ways that we all communicate and hope to connect with each other.

My endorsement of captions and subtitles as the embodiment of accessible communication is mirrored in an exhilarating music video that I had not previously explored: Only ASL One, a song by a D/deaf rapper, Warren “Wawa” Snipe. In this music video, Snipe signs and signs simultaneously with lyrics that appear in synchronization with the music around different spaces of the screen, including the bottom, middle, and top of the screen, as shown in the following images from his music video (Figures 0.1 and 0.2).

Figure 0.1: Warren "Wawa" Snipe's ASL music video with text visually fading in and out with the music

Figure 0.2: Warren "Wawa" Snipe's ASL music video with text visually fading in and out with the music

Snipe, who speaks and signs simultaneously in his songs, developed Only ASL One as a song and music video in which he performs the role of a hearing man who hopes to ask a Deaf woman out on a date. This role finds the hearing man starting to learn ASL to communicate with her, but he has only taken a level one ASL course. Exploring this music video about multilingual communication underscores that captions and subtitles are vital means of accessible multilingual and multimodal communication while revealing the thrill and challenges of connecting with someone across languages, modes, and embodiments.

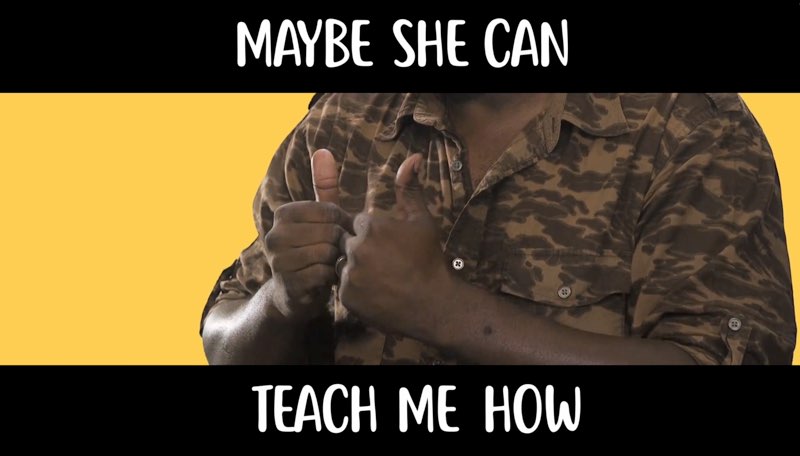

The temporal synchronization and dynamic placement of words around the screen accentuate viewers’ access to the lyrical message as Snipe, in character, simultaneously signs and sings about his desire to connect with a Deaf woman. Throughout the video, he tells us that he has started to learn to sign, wants to learn how to communicate with her, and hopes she can teach him how to tell her he likes her, as shown in Figures 0.3 and 0.4.

Figure 0.3: Lyrics reflecting the hope of communicating across languages

Figure 0.4: Lyrics reflecting the hope of communicating across languages

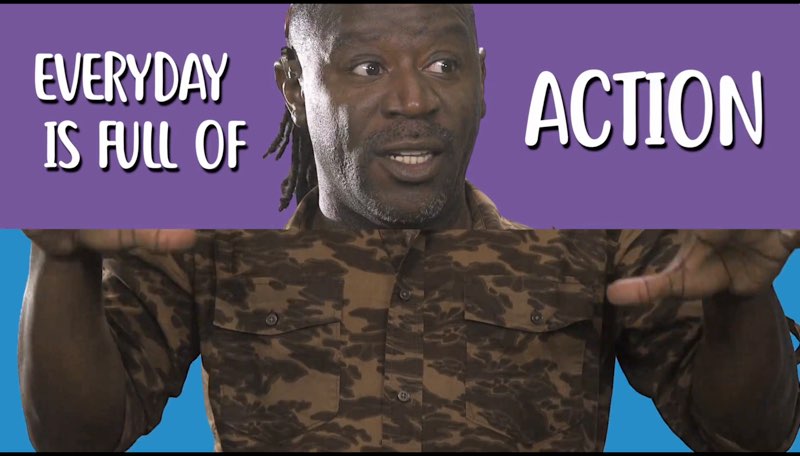

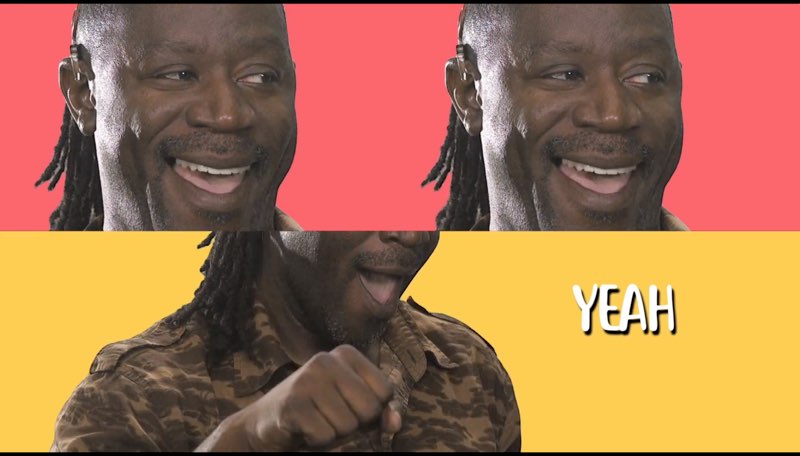

Visual text, signs, speech, and physical expressions juxtapose to reinforce the sensations of attempting to communicate across languages to connect meaningfully with someone. These multimodal juxtapositions are recreated in the music video’s split screens, as shown in Figures 0.5 and 0.6.

Figure 0.5: A multimodal juxtaposition of Snipe's face and body as he sings and signs alongside visual lyrics.

Figure 0.6: A multimodal juxtaposition of Snipe's face and body as he sings and signs alongside visual lyrics.

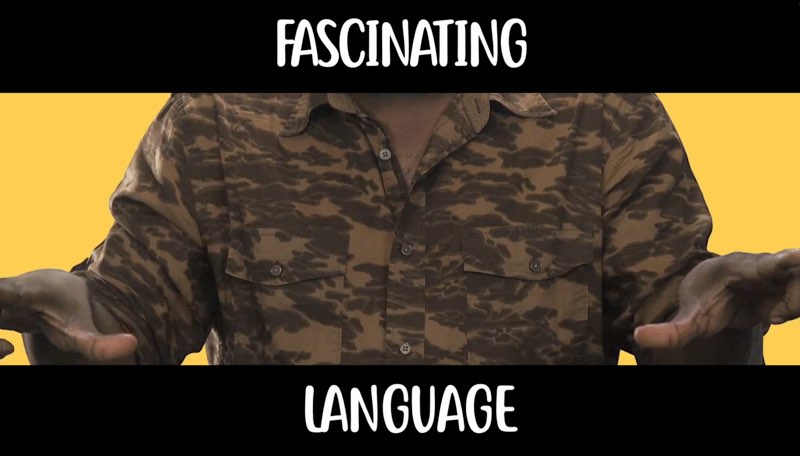

This music video illustrates real-world scenarios where communication is not linear, straightforward, nor simple, and where people can use multimodal strategies (including writing) to express themselves and understand each other. Removing the words from the screen would deprive this composition of its heart, as the written words connect speech with signs. And Snipe embodies this accessible multimodal, multilingual message in one moment of the song when he (in the role of the hearing character) says this of ASL: “fascinating language, wished it came with closed captions” (Figures 0.7 and 0.8).

Figure 0.7: Zooming into the value of language and captions as means of making communication accessible.

Figure 0.8: Zooming into the value of language and captions as means of making communication accessible.

This witty line by Snipe captures the power of captions and subtitles in bridging languages and modes and subverts conventional assumptions that captions are only for deaf and hard of hearing (DHH) viewers. The hearing character here wishes that captions were available so that he could understand ASL and communicate with the Deaf woman—just as those of us in the real world rely on captions and subtitles to understand each other across languages and modes, and just as Snipe the musician intuitively included words on screen to make his message accessible across languages. Snipe’s accessible multimodal message reminds us that captioning and subtitling videos and media enriches communication by making ASL accessible in English and by making spoken English accessible through the written form.

In the real world, digital media (televised, streaming, and online videos) will only become more prevalent in our lives, and so this is the time to entrench captions and subtitles as fundamental means of making multimodal communication accessible. From music videos to professional presentations to streaming media and other contexts, scholars and creators can embrace different strategies for incorporating written text on screen to embody the many ways of communication and connection with each other across differences. In an increasingly machine-generated world, this time can be and should be utilized to affirm our unique embodiments as humans seeking to connect with other humans.

Humans can, as the chapters of this book will show, appreciate different strategies for conveying who we are and who we want to be through captions and subtitles. While Snipe developed a visual design for his music video that emulates communication across spoken and signed languages, this book reviews other media and videos that reveal more possibilities for a variety of captioning and subtitling approaches. Each approach, including traditional captions at the bottom of the screen, reflects the embodiment of the creator or performers and the purpose or message of the program—such as broadcast programs in which spoken English is shown as captions at the bottom of the screen while the embodied language of ASL is translated to English immediately next to signers’ bodies. Captioning and subtitling approaches can create avenues for the audience to connect with the message, the performer, or the creator.

Studying different captioning and subtitling approaches is an act of maintaining a more human world, one in which we honor each other’s embodiments and commit to making digital meaning accessible across multiple modes of communication.

Captions and subtitles may be the driving force of this book, but to best understand how they can be the embodiment of accessible multimodal communication, we should first begin with understanding the vital concept of embodiment. Embodiment includes the ways that each human being experiences the world differently through our own body and how our bodies influence the way that we interpret the world (Knoblauch & Moeller, 2022; Melonçon, 2013; Wilson & Lewiecki-Wilson, 2001). My own embodiment as a Deaf woman has informed how I experience visuals and sounds and has shaped my dedication to multimodal communication. My lived experiences have accentuated my recognition of the value of communicating across modes, the power of challenging conventions to make sounds visual or textual, and the need for making our messages accessible to other human beings. These aspects of my embodiment have all intersected into a recognition of the significance of captions and subtitles and the potential for making them even more central in our analysis and design practices.

Embodiment is a complex term that has, as Knoblauch and Moeller (2022) note, resulted in various definitions of embodiment. I say that these various definitions are not a limitation because they reflect the complexity of who we all are as human beings. Embodiment also includes “the experience of orienting one’s body in space and amongst others” and can be the “result of connection and interaction” (Knoblauch & Moeller, 2022, p. 8). The examples of captions and subtitles shared throughout this book reflect or reinforce the desire for connections amongst individuals, languages, and modes.

The embodiment of meaning through words on screen may be most salient in ASL music videos, similar to when words appear around Snipe’s face and hands in “Only ASL One.” The embodiment of meaning through words on screen may be more subtle in other scenarios, such as in television programs in which a hearing character and a Deaf character attempt to connect across spoken English and ASL with the captions and subtitles visually displaying when characters are successfully or less-than-successfully communicating (as discussed in Chapters 5 and 6). In these and other ways, captions and subtitles are the embodiment of accessible embodiment communication in that their portrayal on screen can reflect how humans experience the world, are shaped by our bodies (including as Deaf individuals or hearing individuals who use different languages), and orient ourselves with each other as we hope to connect through communication.

The concept of embodiment serves a major role in the next chapter, which examines my embodied multimodal framework for analyzing captions and subtitles and delves deeper into the concepts of embodiment and embodied rhetorics. To work towards that framework, the latter sections of this introduction will review key details about various types of captions and subtitles. Throughout the review of these types, keep in mind that captions and subtitles of all types can be the embodiment of accessible multimodal communication. We also can create a space for all types of captions and subtitles in analysis and design practices to respect and support the many ways, languages, and modes that human beings all orient to and interact with each other.

INTRODUCING SPACE FOR CAPTIONS AND SUBTITLES

This book guides readers through a study of captioned and subtitled media in various forms, including:

- Videos that include captions when the same language is being verbalized on screen,

- Videos that include subtitles when a different language is being spoken or signed,

- Television programs and documentaries that include traditional closed captions at the bottom of the screen,

- Programs that embed stylized lines of words permanently into different spaces on the screen,

- Social media videos that integrate highly dynamic words across the screen,

- My own video version of each chapter, and

- Combinations of different captioning and subtitling approaches within the same video.

Such examples reinforce my argument that captions and subtitles can embody the multiple modes and languages through which we communicate and connect with each other (including facial and body language, and signed and spoken languages).

While we analyze meaningful examples of captioned and subtitled videos, we can make the design of captions and subtitles central in our own video composition processes, from academic contexts to social media and other contexts. When space is generated for captions in video analysis and design practices, the value of accessibility and inclusion is reinforced and extended. Video creators can bring together accessibility and creativity when creating different kinds of captions and subtitles that embody who we are as individuals and our multimodal message—all while making our content (including identity and message) more accessible to diverse audiences.

I have chosen to share my multimodal message with my audiences through this digital book to directly address those who are interested in the analysis and design of videos, including online content creators, academics, and students, and to encourage more creators to make captions and subtitles central in video creation processes. My lived experiences as a Deaf academic has led me to study and share videos in which captions and subtitles have been creatively incorporated into different spaces around the screen of a video, especially ASL music videos (Butler, 2016), and Gallaudet: The Film (Butler, 2018b). These innovative media—which were created primarily by and for Deaf individuals—manifest the concept of Deaf Gain, which frames Deaf experiences and our accessible multimodal communication practices as a positive gain for society at large (Bauman & Murray, 2010, 2014). A salient example is Sean Forbes’ (2011) “Let’s Mambo” (Figures 0.9-0.11), an ASL music video in which lyrics pulsate on screen in sync with signs and music.

Figure 0.9: Dynamic lyrics in an ASL music video.

Figure 0.10: Dynamic lyrics in an ASL music video.

Figure 0.11: Dynamic lyrics in an ASL music video.

This book also draws from other examples and my Deaf identity to show the power of Deaf Gain that comes when we appreciate meaningful ways of incorporating captions and subtitles of all kinds on our screens, particularly in multimodal and multilingual contexts that represent our multicultural world of communication. I intend for the chapters of this book (and the examples within) to collaboratively transform the ways in which videos are studied and created: with captions and subtitles and accessibility at the center of our processes. When more people make captions and subtitles valuable in our analysis and design practices, we can contribute to greater accessibility and inclusion in video-based conversations and contexts, including through social media.

The incorporation of dynamic words on screen has exploded since I first studied ASL music videos in 2016, most saliently through TikTok, Instagram Reels, and related social media programs that allow creators to embed words of various styles on screen. As discussed in Chapter 7 of this book, dynamic visual text on screen has become elemental in the larger cultural moment for the aesthetics of social media videos. However, simply placing highly stylized visual text on screen does not make a video accessible, especially when the stylized words visually interfere with other elements of the screen or do not actually caption exactly what the person in the video says.

The meaningful examples in this book—which carefully incorporate captions and subtitles of different kinds, including traditional captions at the bottom of the screen—can serve as models for the effective ways in which words on screen can be designed to be simultaneously accessible and aesthetic. Some of these media have been created by hearing production teams or creators for mainstream audiences while others have been created by and for Deaf individuals; each chapter’s study of these media encapsulates the Deaf Gain that comes when we more deeply appreciate and reinforce the value of captions and subtitles of all kinds in making our work accessible to each other. Before we study other programs and the possibilities for our own videos, we can begin with social media videos and appreciate how creators can balance accessibility and aesthetics when creating words on screen that embody their message and strengthen their connections with audiences.

MULTIPLE MODES WORKING TOGETHER

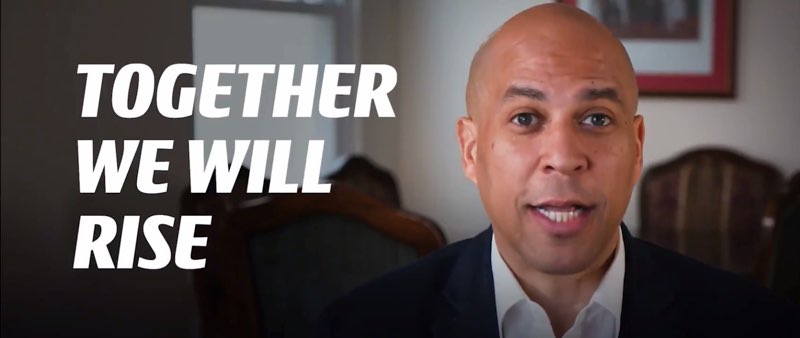

We will now dive into the social media ecology with its growing integration of on-screen visual text and consider a video that effectively balances accessibility and aesthetics. In January 2020, Democratic Senator Cory Booker of New Jersey posted a video on Twitter announcing that he was suspending his campaign for president (Figure 0.12).

Figure 0.12: Tweet by Cory Booker with a video that has embedded open captions

This minute-and-half long video is a montage that combines recordings of Booker giving public speeches with new footage in which he directly faces the camera and speaks to his online audience. Throughout these moments, the video incorporates open captions that are visible, or open, to sighted viewers1. These open captions resonate in social media’s highly visual and multimodal space and make Booker’s message pop out on online audiences’ devices and screens. The effective rhetorical design of the captions embodies his spirit and enhances audiences’ connection with his message.

Booker’s video begins with a black screen where white text slides up word by word to create the first line of captions at the same time he speaks each word. Halfway through the text appearance, the black screen reveals Booker speaking in one of the Democratic Party presidential debates, the captions continuing to appear in synchronization.

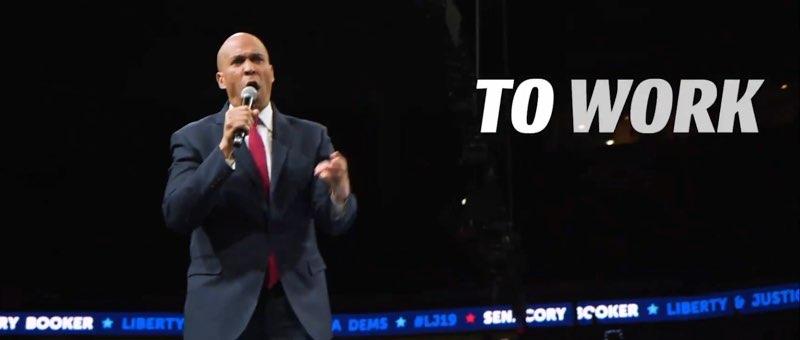

The video continues with clips of Booker’s speeches as open captions appear word by word in temporal alignment with his phrasing. The following screen captures (Figures 0.13 and 0.14) show how equal space is dedicated to Booker and to the visualization of his words.

Figure 0.13: A scene in Cory Booker’s video with open captions embedded in prerecorded content

Figure 0.14: A scene in Cory Booker’s video with open captions embedded in prerecorded content

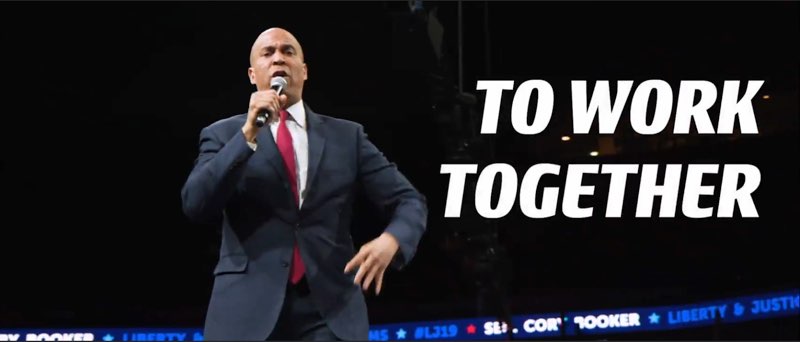

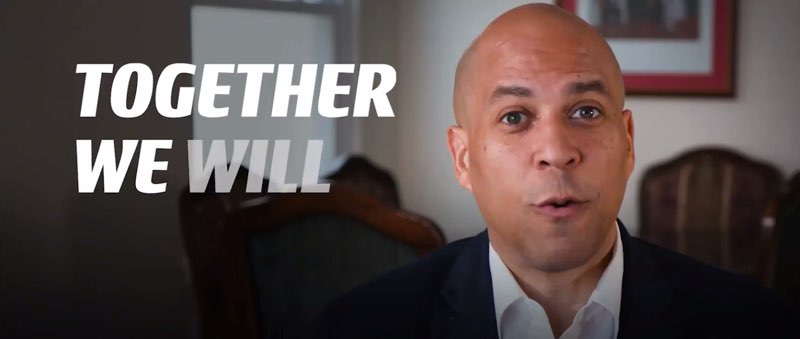

Intermingled with these clips of speeches are new moments in which Booker directly faces the camera as he speaks directly to his audiences. While describing his decision to suspend his campaign, he uses his voice, powerful direct gaze at the camera, and open captions to emphasize the value of everyone joining together to support each other and the common cause for the country, as shown in the following screen captures (Figures 0.15 and 0.16).

Figure 0.15: A scene in Cory Booker’s video with space dedicated to captions

Figure 0.16: A scene in Cory Booker’s video with space dedicated to captions

The open captions in Booker’s video embody his cadence, spirit, and call to action, strengthen the connection between speaker and audience, and make his message visually accessible by showing viewers his voice as a speaker who values collaboration.

The design of the open captions varies throughout different moments in this video. Open captions have been added to the bottom of the screen or to the side of the screen in the recordings of speeches and debates depending on where Booker stands on each stage. When there is space next to Booker’s body, captions are incorporated next to him (Figures 0.15 and 0.16).

Booker’s video, presumably created for a predominantly hearing audience, encapsulates the power of connection created through designing captions that embody our identities and the value of multimodal communication through sound, visuals, and other expressive modes. Concurrently, the intentional design of these synchronized captions makes the deep spirit and heart of his voice accessible to a wider online audience in ways that exceed the affordances of traditional captions that might only transcribe his words in textual form. While the open captions speak to online audiences, the open captions even more crucially create visual access to his aural message for d/Deaf2 and hard of hearing (DHH) viewers.

When I first watched this video during that year’s presidential campaign, the synchronized captions enhanced the sensation of Booker’s voice reaching out past the screen and intensified his direct gaze at me, a Deaf rhetoric and composition scholar who is committed to improving the accessible design of captions that embody the many ways that we all communicate and connect with each other. The captions connect speaker with audience and reflect how we all interact with each other through multiple modes, or ways, of communication. We engage in multimodal communication through voices, body language, written text, and other communication strategies in different contexts online and in our physical lives.

Booker’s video also reminds us that access to political conversations embodies the value of being able to engage in real-time conversations and participate in society amid the eternally exponential growth of online video content and the endless stream of films, series, and advertisements being created and distributed. Colleagues, students, social leaders, public figures, friends and family, and other individuals compose and create videos to share with each other online as DHH individuals navigate a world of captioned and subtitled television programs, films, and advertisements. Access to this cultural content occurs when we all caption our videos and media and affirm the importance of captioning for access online (NAD, 2023a, 2023c).

We must begin with the recognition that captions and subtitles are irreplaceable means of access to video content and we must center the needs of those who access sound through captions and subtitles: DHH individuals. With that fundamental truth, we individuals with all different hearing levels can embody our identities, our languages, our voices, and our connections with each other through the design of captions and subtitles on our screens.

To unpack the potential for captions and subtitles of all designs, this book is a curated collection of meaningful examples of captions and subtitles that make multimodal, multilingual, and multicultural communication accessible to a wide range of audiences with different hearing levels. The variety of approaches to captioning and subtitling videos and media embodies the assortment of ways in which we communicate in our lives and the interdependent process in which dialogic participants coordinate and support each other’s access to meaning through different modes, languages, and ways of understanding.

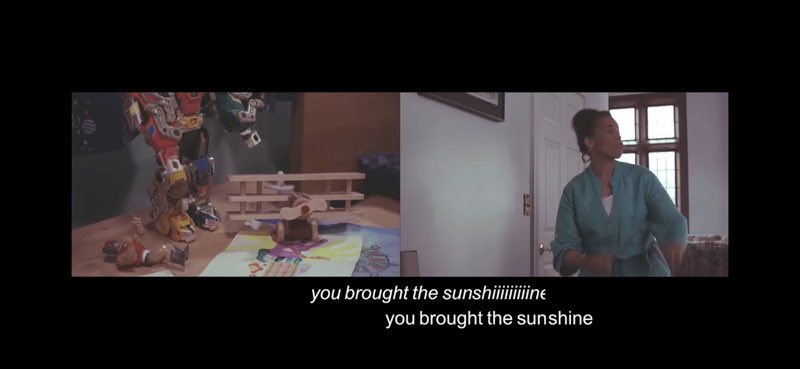

An ASL music video presented by the Deaf Professional Arts Network (D-PAN) reveals the value of captions and subtitles on screen, including when placed at the bottom of the screen. Throughout some moments in the ASL cover of The Clark Sisters’ You Brought the Sunshine (D-PAN, 2013), the lyrics scroll out letter by letter at the bottom of the screen, as shown in Figures 0.17 and 0.18. The sensation and multiple layers of the words can be felt in the body as each lyrical moment appears in tandem with the music. In this case, the words do not need to be highly colorized or vibrant—and the tasteful design captures the vocals in textual form.

Figure 0.17: Lyrics scrolling out letter by letter at the bottom of the screen in an ASL music video

Figure 0.18: Lyrics scrolling out letter by letter at the bottom of the screen in an ASL music video

In this movement through a variety of captioned and subtitled spaces and screens, we will determine the affordances—the benefits and limitations—of captioning and subtitling multiple modes of communication (including multiple languages and embodiments) in different contexts. Our journey will be guided by the six criteria of my embodied multimodal framework; these six criteria serve as a paradigm for identifying and evaluating the accessibility, effectiveness, and applicability of each captioning and subtitling style or trend. As the variegated styles reveal, there is no one-size-fits all in our day and age; rather, there are rhetorical and aesthetic choices that each captioner—and we are all captioners—makes to embody the interdependent process of accessing communication in all its forms. The common thread of connection and access across different abilities, identities, modes, and languages ties together each trend.

The variety of approaches buttresses this book’s argument for my readers: that we instructors, scholars, students, and creators who analyze and compose video content can value the design of captions and subtitles that embody the connections amongst participants in a dialogic situation: video creators and composers, actors and performers on screen, and audiences. I include screen captures and image descriptions throughout this book to give us the time and space to process each captured moment thoroughly, particularly the visual representation of captions and subtitles on screen alongside the bodies of performers.

Captions and subtitles—from highly stylized captions that are integrated into the space of the screen to traditional captions at the bottom of the screen—are central in the screen-based conversations in this book. As we move through each space, we can recognize how space has been dedicated to captions and subtitles, from the literal design of space on the screen (such as the space next to Booker’s face) to dialogic space when video creators and audiences attend directly to the affordances of captions and subtitles.

These captioned and subtitled spaces verbalize the multilingual, multicultural, and multimodal times in which we live, depend on, and interact with those around us online and offline. As we center captions and subtitles in these explorations, we can ourselves embody direct access to communication and interdependence with each other when we recognize this commonality: the design of captions and subtitles is central to our video composition practices and our multimodal/cultural/lingual communities as we connect across differences.

DEFINING CAPTIONS AND SUBTITLES

Since I am asking my readers to appreciate the layers of captions and subtitles more deeply in video compositions, I will begin with defining key terms to lay the groundwork for our assessment of a variety of captioning and subtitling styles that connect participants in a conversation and creators with audiences.

Definitions of captions and subtitles are context-specific depending on our nationality, the technology we are referring to, and the media that the captions and subtitles appear on.

Depending on context, I use the umbrella term captions to refer to both captions and subtitles. However, the two terms deserve equal status, especially to reflect our multilingual world and the core value of communication access, including access across languages. The following definitions are used in this book:

- Captions: Written text on screen that is in the same language as what is being spoken on screen

- Subtitles: Written text on screen that translates the language being spoken or expressed on screen

Using that definition, then, Cory Booker’s video as shown in Figures 0.13-0.16 includes English-language captions for his spoken English speech.

Also, in this book, captions refer to same-language text while subtitles refer to contexts in which the language on screen is different from the language being written. For instance, in ASL learning videos, English words are placed around the screen for new learners unfamiliar with ASL, the language being expressed on screen. So, if ASL is the primary language on screen, then English subtitles on screen provide access to ASL.

In literature from other nations, particularly England and Europe, definitions of captions and subtitles are flipped. Subtitles refer to those for DHH people, while captions refer to foreign-language contexts (for example, Matamala & Orero, 2010; Zárate, 2021). This is complicated further by the use of captions and subtitles specifically within the context of foreign language media and second-language acquisition scholarship. This scholarship distinguishes interlingual subtitles from intralingual subtitles. Intralingual subtitles are captions provided in the same language as that spoken on screen; that is, they are “same-language subtitles” (Gernsbacher, 2015, p. 197). Conversely, interlingual subtitles are translations of the spoken language into the viewers’ language and the primary purpose of interlingual subtitles is to “grant wider-scale access to the audiovisual product by individuals speaking a different [first language]” (Ghia, 2012, p. 1). To emphasize, interlingual and intralingual captions and subtitles provide viewers with textual access to languages, and access to meaning, is at the heart of our multilingual connections with each other.

This book, which is grounded in the U.S., uses captions when exploring spoken English contexts and subtitles when exploring multilingual contexts. When exploring other videos with multiple languages being expressed on screen such as spoken Spanish and when composing my own ASL videos, I use the term subtitles to refer to the written text that appears on screen. These subtitles translate the spoken or signed language into English for English-using audiences who might not be fluent in the original language, incorporating awareness or assumptions about the target audience’s knowledge of the original language.

A subtitled video that demonstrates awareness of target audiences is a promotional video for The ASL App, an app for learning ASL that “is made by Deaf people for you!” (The ASL App, 2013). In this promotional video, the camera shows a barista at a coffeehouse practicing the signs for ordering coffee using this app on his phone. He then waves hello to a customer at the counter who signs “Hello” back. The barista then asks, “COFFEE?” in a large blue uppercase font floating on screen between him and the male customer. “COFFEE?” fades off screen as the customer’s response, “YEAH!”, appears on screen in the same large blue capitalized font floating on screen in sync with their signs, as captured in the following shot (Figure 0.19). Each word appears closer to the person who signs the phrase, but always in the space between the bodies and in proximity to the hands.

Figure 0.19: Words appearing near signers in interaction

Through these and subsequent subtitles, hearing audiences can access the core message embodied in the app that has been designed to support the development of their ASL skills.

The focus on both captions and subtitles in this book reflects an international world of communication and becomes especially valuable in the exploration of subtitled multilingual and multicultural spaces throughout the chapters to come. By attending more closely to subtitled videos, we can further commit to designing inclusive spaces that layer multiple languages and cultures.

Closed Captions and Open Captions

In the exploration of captioned and subtitled media, we access meaning through closed captions as well as open captions and open subtitles. Open captions are embedded into the screen for all sighted viewers to see, as demonstrated in Booker’s video. The words or lines of written text cannot be removed or moved by the viewer. Social media and other online videos have increased the use of open captions over the last decade or so, with that trend intensifying thanks to the creation of TikTok videos that incorporate open captions. The prevalence of open captions on social media for a predominantly hearing audience that might be watching videos with the sound on or off on their phones is a fertile ground for spotlighting the value of captions for audiences with all hearing levels. This is explored further in Chapter 7.

Subtitles are often open to viewers because of the assumption that general audiences might not know the target language and the subtitles provide them with access to the language being expressed on screen. It is important to note that open captions and subtitles are different from closed captions. The use of closed captions originated on television screens (NAD, 2023c) and the word “closed” reflects how they can be turned on or off (NAD, 2023e). Sighted viewers in the United States might recognize closed captions as white font against a black background at the bottom or top of the television screen, as shown in the following screen capture (Figure 0.20) from Born This Way Presents: Deaf Out Loud (Matlin, 2018), which is explored further in Chapter 4. However, televisions and online content often have captions off as the default, which forces the viewer to actively turn on captions for access.

Figure 0.20: Closed captions at the top of the screen

While I, like the National Association of the Deaf (2023e), use the term “closed captions” to refer to captions that can be turned on and off, some only use “closed captions” to refer to captions that textualize English and include sound descriptions in brackets. Captioning expert Sean Zdenek (2015) clearly delimitates what counts as closed captions for his groundbreaking rhetorical study of closed captions. Closed captions provide “the full complement of sounds” for deaf and hard of hearing audiences (Zdenek, 2015, p. 35), notably with descriptions of sound in brackets.

The federally-funded, non-profit organization Described and Captioned Media Program (DCMP) (2023b) clarifies that captions “not only display words as the textual equivalent of spoken dialogue or narration, but they also include speaker identification, sound effects, and music description.” In essence, closed captions provide descriptions of sound for DHH audiences in addition to transcribing spoken English into written English. Sound descriptions include “[laughs]” when a character laughs, as shown in Figure 0.21, which comes from New Amsterdam and which is analyzed further in Chapter 5.

![Two characters both hold a phone and each other's hands. The phone screen shows an iPhone text message conversation. Closed captions at the bottom state, "- [laughs]."](images/newamsterdams5ep9_3_laughs.jpg)

Figure 0.21: Closed captions with sound description in brackets

While specific styles and guidelines for closed captions differ across different organizations (Zdenek, 2015, p. 53), commonly suggested standards for closed captions are crucial to the development and application of possible caption/subtitle designs, open or closed.

The DCMP (2023a), provides an extensive captioning key that clearly establishes the “elements of quality captioning” (2023b). Furthermore, DCMP provides five points as the elements of quality captioning :

- Accurate: The captions are “errorless.”

- Consistent: The “style and presentation” of captions are consistent.

- Clear: “A complete textual representation of the audio” [including through description of non-speech sounds and speaker identification in brackets] “provides clarity.”

- Readable: “Captions are displayed with enough time to be read completely, are in synchronization with the audio, and are not obscured by (nor do they obscure) the visual content.”

- Equal: “Equal access requires that the meaning and intention of the material is completely preserved.” (DCMP, 2023b)

These five points refer more specifically to closed captions but should be fundamental in any caption creator’s development, and these principles inform this book’s investigation of the accessibility of different approaches to captions and subtitles, including ensuring that captions and subtitles are displayed with enough time to be read completely and do not obscure or are not obscured by visual elements.

Maintaining a strict definition of closed captions can be challenging in different contexts. Notably, DVDs of spoken English films and shows often provide what they call “subtitles” for DHH viewers that can be turned on and off, and the visual text on screen for DVDs emulates the style of subtitles rather than closed captions.

Rather than treating these differences as complications, we would be well-served to seize this complexity in how we compose captions and subtitles of different varieties and multiple languages in the commitment to connecting with each other and our audiences. To study these varieties, the technical presentation and creation of captions and subtitles—whether they are baked into the video (open) or can be toggled on and off (closed)—and the distinction between same-language captions and subtitles for different languages can be distinguished as layers of meaning that strengthen access to multimodal and multilingual meaning.

Integral Captions and Subtitles

A fundamental principle at the heart of this book is the power we all hold as creators who can compose access while embodying our identities. While there are benefits to automatically generated captions—including convenience and fast turnaround so that videos with spoken content can be quickly captioned—automatically generated captions cannot capture our voices as creators expressing intricate meaning to each other. Automated captions are the opposite of what I call integral captions and subtitles, or captions and subtitles that creators carefully design to be essential elements of a video in coordination with sound, body language, and other modes of communication (Butler 2018b; Rhetoric Review). Integral captions and subtitles are a form of open captions and subtitles as opposed to closed captions.

Integral captions and subtitles are primarily open captions and subtitles because they are designed as part of the viewing experience, and they go further because they are integrated into the space of the video, interact with other elements of multimodal communication, and provide visual access. ASL music videos integrate highly dynamic visual lyrics—text that morphs, shimmers, and dances across the screen alongside signing bodies to make the spirit, beat, and heart of music accessible in visual form (Butler, 2016). In Sean Forbes’ (2011) electrifying “Let’s Mambo,” which is shown in Figure 0.22, and other videos, captions and subtitles3 are not an afterthought, but are designed to interact with the sound and the action on screen, embodying the pulsations of the beat and the vibrations of the music.

Figure 0.22: Highly dynamic visual lyrics in an ASL music video

While the highly vibrant lyrical text in some ASL music videos is suitable for these contexts, this book does not intend to argue that all videos should incorporate highly stylized visual text. There are many ways in which captions and subtitles—including linear captions and subtitles that do not necessarily move across the screen—can exemplify accessible multimodal communication. The first few chapters of this book guide readers through innovative integrative designs of captions and subtitles that enhance the creator-performer-audience connection. The examples of captions and subtitles embody performers’ rhetorics while facilitating audiences’ abilities to attend to meaningful moments on screen, including performers’ facial expressions and other key nuances.

My commitment to integral captions and subtitles in certain contexts builds on my viewing experiences dividing my own attention between captions and subtitles at the bottom of the screen and performers’ eyes, facial expressions, and action on screen. Studies have demonstrated that caption readers have to commit time to reading captions as opposed to viewing the screen (Jensema et al., 2000), that viewers focus more on faces than other images when dividing time between reading captions and subtitles and looking at the action on screen (Perego et al., 2010), and that captions and subtitles “compete for visual attention with a moving image” by drawing viewers away from faces on screen (Kruger et al., 2015, n.p.). With performers’ faces and action embodying important messages, we can design a space for captions and subtitles next to bodies and bring viewers’ eyes to the heart of the video, as shown in Figure 0.23 (Densham & Raff, 2015) from Heroes Reborn, a show that integrates subtitles into the space of the screen in Japanese-language scenes.

Figure 0.23: Subtitles that are integrated into the screen and embody imagination

The integrative examples in this book can serve as models for the innovation and creation of videos in which visual text that captures our message and the hearts of our audiences is carefully composed. These models show the strength of multimodal communication through visual text that is meaningfully designed and placed in interaction with bodies, sound, and other modes of expression and reception.

More recently within the past decade, YouTube and a growing number of online platforms have provided online viewers with the option to customize the size, font, color, background, and other aspects of their “closed captions” for individualized reading experiences. This technological advancement facilitates visual accessibility since viewers can choose the most comfortable size and color for reading.. With this option available to viewers, content creators can continue to design intentionally creative and meaningful captions that capture the heart of our embodied messages and reveal who we are and what we want to be as humans to our audiences across languages, abilities, and experiences.

Integral, Open, and Closed Captions and Subtitles

While integral captions and subtitles are models of accessible multimodal communication through visual text, my goal is not to argue that every single video creator should integrate captions and subtitles within the space of their screen every single time. All compositions are context-specific, and creators have their own purpose and embodiment, and integral captions and subtitles are one valuable instrument—but certainly not the only instrument—in our captioning orchestra. However, what I do want to demonstrate is how we create more possibilities for genuine connection and access to meaning when we play intentionally with different instruments, including in the same space, for all caption types. Content creators, instructors, students, and those who analyze and compose videos in different contexts should view captions not as an inanimate tool to deploy, but as an instrument that, when played in harmony with other instruments, can create a multilayered composition that in turn stimulates sensations in audiences.

The thread that ties together instruments and examples is the importance of carefully considering how to make communication accessible through visual text beyond simply adding captions to satisfy accessibility requirements. With new developments in technology occurring seemingly every second, we can maintain our strengths as common citizens of the world of humanity and engage in the interdependent process of composing captioned and subtitled access to multimodal and multilingual communication.

JUXTAPOSITION: EMBODYING MY MESSAGE THROUGH VIDEO VERSIONS OF CHAPTERS

Through this book, I ask readers to imagine the possibilities for incorporating captions and subtitles more meaningfully in our video analysis and design processes. To illuminate the benefits of placing captions and subtitles at the center of video composition, I have created short videos in which I express my multimodal and multilingual message through signs that interact with subtitles. Each chapter includes such a video with voice-overs spoken by an ASL interpreter. This is so I can demonstrate my embodiment as a Deaf multimodal composition scholar and incorporate my multimodal and multilingual argument about the value of designing a space for captions and subtitles in video composition processes. The videos may become springboards that inspire video composers—including content creators, instructors, and students—to meaningfully include captions and subtitles in videos for online dissemination, academic contexts, and other spaces.

In addition to presenting my video in each chapter, I highlight key moments from each video, including moments in which I explicitly use the words on screen to embody my argument and emphasize how creators could design a space for words on screen in different creative processes. Through this process, I aim to demonstrate the potential and benefits of incorporating captions and subtitles in video creation processes, including in academic and professional contexts.

Let’s begin with my first video.

Several moments in this video demonstrate the possibilities for designing space for captions and subtitles on screen and strategies that creators can include when creating videos. Throughout the clip, words appear near my upper body and face as I purposefully look at and gesture to the space right next to me to draw viewers’ attention to my expressions and the words.

The strategies that I use can be emulated and revised by video creators who might use different approaches to caption or subtitle videos. Near the beginning of this video, subtitles appear near my face and upper body that share my name. In this moment, I hold one hand under my name and use my other hand to fingerspell my name in ASL. Through this juxtaposition, I make my name accessible in ASL and English simultaneously. Creators can likewise celebrate the affordances, or benefits, of communicating through multiple modes and languages at the same time, and interact more meaningfully with words on screen to make messages accessible.

The final chapter includes my reflection on my process of composing these videos and my guidelines and implications for video creators.

OVERVIEW OF CHAPTERS

Each chapter works successively to guide readers through the design of captions and subtitles as the embodiment of our identities, as a reflection of how we engage in the interdependent process of communicating across modes and languages, and as a core component of our conversations about the value of access and differences in our multifaceted world. Below is a quick overview of each chapter.

An Embodied Multimodal Approach to Visualizing Captions and Subtitles

To provide a foundation and a framework for visualizing captions and subtitles as the embodiment of accessible multimodal communication, this chapter first connects the key themes of embodiment, space, access, multimodality and caption studies, and interdependence. I then detail my embodied multimodal approach to analyzing the design of captions and subtitles. The embodied multimodal approach includes six criteria that foreground space, access, embodied rhetorics, multimodal and multilingual communication, rhetorical and aesthetic principles, and audience awareness. That in turn segues to the following chapters of the book in which we explore spaces that demonstrate the value of captions and subtitles in our collaborative work to communicate and connect across modes and languages.

Integral Subtitles in Embodied Multilingual and Multimodal Spaces

This chapter presents my analysis of two contexts that were instrumental in the development of my original criteria for the analysis of integral captions and subtitles. I assess two examples from contemporary popular media—Heroes Reborn and Sherlock—to reveal the ways that these two shows’ use of integral subtitles embodies their respective hybrid worldviews and the fluid interplay of modes in each show. Heroes Reborn provides English-using viewers with visual access to spoken Japanese through English-language subtitles on screen while Sherlock integrates visual text and subtitles in scenes in which languages and modes other than spoken English play out on screen.

The Design of (Deaf) Space for Connections

In this chapter, we design a (Deaf) space for connections to fully appreciate how the meaningful integration of captions and subtitles can create greater opportunities for experiencing embodied differences and multisensory connections. We begin with the principles of Deaf Space and Deaf Gain in preparation for our subsequent deeper dive into the holistic experience of Gallaudet: The Film, a short silent film that captures Deaf experiences. In a previous publication in Rhetoric Review, I succinctly analyzed how this film designs a Deaf Space for words on screen, particularly in classroom moments from this film (Butler, 2018b). In this current chapter, I apply the embodied multimodal approach in my full analysis of the holistic film to fully unpack how this film embodies deaf aesthetics with integral captions and subtitles that immerse viewers into a multidimensional space created through and for visual-spatial connections. The accessible and aesthetic design of captions and subtitles in this film shows us the value of designing spaces for learning through differences on our screens.

Integration of Captions and Subtitles, Access, and Embodiments

In this chapter, we shall bring Deafness and disability to the center of our screens. Our journey will take us through several spaces in which DHH, hearing, and disabled characters communicate not only with each other, but with us, the audience through integral captions and subtitles that appear in predominantly closed-captioned productions. The integration of captions and subtitles in hearing media represents the benefits of designing a space for different embodiments. These spaces include Born this Way Presents: Deaf Out Loud, Crip Camp: A Disability Revolution, and The Company You Keep. Through the embodied multimodal approach, we can explore how the languages and identities of real individuals and characters are made accessible through integral captions and subtitles. Most of all, the design of these captions and subtitles underscores the value of communicating and connecting across differences.

Interdependence and Connections in New Amsterdam: A Case Study

While the previous chapters centered on integral captions and subtitles as the epitome of embodied accessible multimodal communication, we must recognize that highly aesthetic and creative design of captions may not be feasible or appropriate across different contexts. As we transition to the next few chapters in which I explore how captions and subtitles can reflect the many ways in which we connect with each other in our lives, this chapter presents a case study of one significant example in which two characters on a mainstream television show, New Amsterdam, engage in the interdependent process of learning to communicate with each other—and concurrently, the audiences engage in this interdependent process through accessing closed captions, open subtitles, and other visuals on screen. This chapter’s analysis of the progression of the relationship between two characters in New Amsterdam reflects the interdependent reality of our lives as we bridge meaning across modes, technologies, and languages.

The Sensation of Silence and Sound with Words on Screen

In this chapter, I explore examples in which sound and silence become embodied and accessible through captions and subtitles and visual text on screen, as in “silent episodes” in television shows in which characters do not speak for an entire episode and as in video compositions in which creators make perceptions of sound and silent signs accessible through written words. My analysis of the benefits and limitations of these methods leads to the second part of this chapter in which I unpack some accessible practices of composers who make sonic and silent meaning manifest through accessible and aesthetic design of words on screen as the embodiment of the multifaceted world of communication that we all navigate online and offline.

Spaces for Captions and Subtitles in Our Conversations

This chapter dives into the affordances of designing a space for captions and subtitles in our conversations, including online conversations and cultural and social conversations. I curate several conversations about and with captions and subtitles, including online videos and advertisements that incorporate subtitled multilingual conversations, videos that show sound through visual text on screen, and creators who meaningfully incorporate captions and subtitles in their videos to connect with audiences across cultures and languages. Through assessing these conversations as well as the benefits, limitations, and challenges of different captioning and subtitling approaches, we can better appreciate the options we have in embodying our rhetorics and committing to accessible multimodal communication online and offline.

Conclusion: Reflections and More

In the conclusion, I reflect on the value, affordances, and implications of captioning and subtitling videos. I share my process of composing and subtitling the video version of each chapter and I discuss implications and guidelines for all of us who analyze and design captions and subtitles of all styles in our journey through accessible multimodal communication.