The multi-textual screens that we have navigated throughout the last few chapters have created a four-dimensional map (including the dimension of time) of the intersecting worlds within which we interact with each other. Social media and its associated digital technologies, including the ability to create videos with captions on our personal devices, seems to be the singular social development that has made adding text to videos a much more common practice for content creators outside of professional filmmaking and media, and outside of composition courses where instructors were asking students to experiment with dynamic visual text in videos before the launch of TikTok (Butler, 2016). The wide variety of approaches include creating closed captions that can be turned on and off for relatively longer YouTube videos, embedding lines of open captions at the bottom of intimate Instagram videos, and experimenting with adding TikTok’s highly visual text to short-form vertical videos.

With social media users creating content on a more frequent basis than ever before, we are at an ideal moment for designing a permanent space for captions and subtitles in our conversations and in our videos. Rather than survey the unfathomable number of videos online, this chapter dives deep into the affordances of designing a space for captions and subtitles in our conversations, including in our screen-based online conversations and on our video screens.

This examination of captions and subtitles includes advocacy for captions and subtitles, online videos and advertisements that incorporate subtitled multilingual conversations, videos that explicitly show sound through visual text on screen, and creators who meaningfully incorporate captions and subtitles in their videos to connect with audiences across cultures and languages. This exploration also includes the benefits, limitations, and challenges of different captioning and subtitling approaches. Through this process, we can better appreciate the options we have in embodying our rhetorics and committing to accessible multimodal communication online.

DIALOGIC SPACE FOR CAPTIONS ONLINE

The fight for captions and access dates back to the early decades of uncaptioned television in the twentieth century, as captured in Turn on the Words! Deaf Audiences, Captions, and the Long Struggle for Access, and the “battles” for access moved online in our century with the explosion of mostly uncaptioned video content (Lang, 2021). While the National Association for the Deaf (NAD) fought, made significant progress, and continues to fight for more captions and access, Ellcessor’s (2016) review of the history of digital media accessibility makes manifest how online users cannot be legally required to caption their videos. As a result, it is up to individuals, communities, and organizations to advocate for captions and access and create more dialogic spaces for captions online.

Ellcessor (2018) has further analyzed how Matlin, one of the most famous celebrities who is Deaf, has used her social media platform to engage in online activism. Notably, she has shared her personal experiences struggling with the lack of captioned media on airplanes and called on social media followers to advocate for captioned in-flight entertainment, as shown in the following screen capture (Figure 7.1) of a social media post (Matlin, 2022).

Figure 7.1: Advocacy online for captions and access

The need for captions and access reaches across the generations, with young actress Shaylee Mansfield, also Deaf, likewise capitalizing on her social media reach to advocate for captions on airplanes. In a vertical video posted on Instagram with open captions embedded near the center of the screen, Mansfield (2023a) demonstrated the struggles of having to search through the seatback monitor for a limited number of media with captions. At the end of the video, instead of signing the last part, she points to words that appear on screen, as shown in the following screen capture of her post (Figure 7.2).

Figure 7.2: Pointing to captions that show a side note (that is not signed or spoken in the video) about the importance of access

In this video, Mansfield consciously creates a space for subtitles and captions to appear and points to the captions to emphasize what ends up a powerful counterargument against those who might accept the status quo.

Matlin and Mansfield are only two of many activists who spread awareness of the need for companies and individuals to caption their videos. This collaborative commitment to access is to be celebrated while we acknowledge the frustrating reality of having to advocate for access in the first place because too many videos posted online have not been captioned effectively or immediately. The lack of equal and immediate access to online video content is the driving force behind users’ comments and original videos throughout social media platforms asking platforms and users to make captions available. Li et al. (2022) visually capture the widespread advocacy in their paper’s opening figure: a collage of screen captures of 10 content creators’ videos with the visual hashtag, #NoMoreCraptions. They build on their analysis and survey of YouTube content creators to recommend, among other points, improving captioning quality (including through algorithms and community captioning), and most intriguingly, recommending that videos ensure “opportunities with lip-reading” (p. 19) that would increase DHH viewers’ access to information in a video. The sentiment is clear: more and better captions are always needed.

At the risk of excluding countless other moments of activism, I will evaluate one effective example here to show how advocates can improve captions and access online, and to show how we can create new dialogic spaces for captions as shown in Figure 7.3.

In response to an uncaptioned video that actor Ryan Reynolds posted on Twitter (now X) in December 2019, a Deaf user, cryssie, commented about the lack of captions and offered the actor captioning resources. In response, Reynolds posted an open captioned version within the next day and even included sound description in brackets.

![Screenshots of a thread on Twitter/X shows the first tweet by Ryan Reynolds, who writes, "Exercise bike not included. #AviationGin." Included is shows an uncaptioned video. Under that tweet is a post by a user who writes, "Ryan... you'll probably never see this. B/c this video is not captioned, everyone else who is hearing get to talk & laugh about this video but many Deaf people including me dont get to do that. DM me if you need resources to caption your video. Much love and thanks from me." Her tweet ends with a smiling emoji and an emoji of the ASL “I love you” sign. The second shows is a reply from Ryan Reynolds saying, "Here you go." His reply includes the same video, now captioned. The captions in this video read, "[Christmas Music Playing]"](images/ryanreynolds_twitterthread1.jpg)

Figure 7.3: Tweet thread that shows how advocacy and access is a collaborative effort

What makes this quick response even more memorable is his follow-up tweet explaining that for some reason the sound did not work in his captioned video and that he is “not good with technology” (Figure 7.4).

Figure 7.4: Tweet by Ryan Reynold that shows how creating videos with captions and sound is a process

Following this post, the thread shows other users who also captioned the video and those who included audio in captioned versions, showing collective commitment and effort. This example captures the beauty of captioning access: that access is a process, not a perfect solution, that we can all learn from each other while making mistakes along the way and while developing new skills for working with technology, and that we can all contribute to a community and culture of access.

What we cannot discount is this: this public figure was willing to post a video without sound so that a captioned version would be available, and in doing so, he transformed the video into a silent space and created a collective experience for all sighted users. This version of the video made captions a viable means of access for viewers to engage with the message, including the music. Furthermore, the multiple versions of this one video in the same thread with and without captions show how these users created a dialogic space for captions. Scrolling through Reynolds’s social media page in later years shows that he continued to include open captioned videos. The message implanted itself: there is always time and space for captions here.

This one social media thread produced several different captioned versions of the same video created by different users, including Reynolds himself. That multiverse was created by the choices each user made in captioning their video, and these users chose to create traditional lines of words at the bottom of the screen, making their message readable and accessible on social media. The choices social media users might use to caption the same video might be different in a different social media context, such as the dissemination of vertical videos with visual text on platforms like TikTok, and that is where we will launch to next.

ACCESS AND AESTHETICS IN ALIGNMENT

On TikTok and similar platforms in which users are provided with more options for embedding colorfully visual text in relatively more informal short-form videos on that platform, the benefits and limitations of designing a space for words on a vertical smartphone screen may be discerned.

The ability to choose from a colorful and dynamic variety of styles is an incredible affordance, or benefit, for several reasons. New creators can recognize the variety of ways in which they can express themselves, they can enjoy the enhanced process of selecting different ways to show exactly how they feel in any given video. They can hopefully appreciate the value of making words visual and making visuals textual. Their integration of words and images on screen can further bring attention to the multi-textual nature of communication—and most of all, with every new video that they create, they contribute to our multi-textual society and intensify our fellow citizens’ ease with languages on screen. That, in turn, could further transform captions into a core value for video communication in society, especially in light of the relatively prominent role of TikTok in young adults’ lives and the frequent nature to which users scroll through social media with phones on mute in public places.

The visual nature of online communication is captured by Justina Miles, a Deaf nursing student who received widespread acclaim during the 2023 Super Bowl when she performed the ASL version of Rihanna’s halftime show as well as the ASL version of Sheryl Lee Ralph’s pregame performance of “Lift Every Voice and Sing” (Breen, 2023). Her performances were streamed live online as part of the NAD’s continual commitment to providing live access to the ASL version of each year’s Super Bowl performances. In a post-Super Bowl interview “CBS Mornings,” Miles described the importance of using her body to visually perform the songs (Breen, 2023).

The power of visual performance—and written words—is discerned in just one instance of a TikTok-style vertical video posted on her Instagram page in which she signs part of a song with visual text embedded above her (Miles, 2022). Colorfully visual captions for the lyrics are superimposed right above her head as she signs each word. The following screen captures (Figures 7.5, 7.6, and 7.7) show three moments in her clip as she signs the word “side” with three different typographical choices.

Figure 7.5: Three different choices for the colorfully visual design of the same word in a vertical video

Figure 7.6: Three different choices for the colorfully visual design of the same word in a vertical video

Figure 7.7: Three different choices for the colorfully visual design of the same word in a vertical video

This shows the range of options for embedding visual text on screen, including placing words near faces as embodied messages are performed. This example also reflects the incorporation of visual text at the top of the screen, a placement practice or trend that seems to be used relatively more frequently in vertical videos than in horizontal videos. From the designer’s perspective, the placement of text at or near the top of vertical videos capitalizes on the extra space and draws mobile viewers’ attention to the key information in the text. From the viewer’s perspective, the placement of text near the top can facilitate our gaze as we read the words and the faces and action right underneath the words. From both perspectives, designers and viewers connect through the text’s placement above those on screen and the top part of the screens that we hold in our hands.

A major positive affordance of social media platforms like TikTok’s incorporation of visual text options is certainly the variety of choices that users have and the ease to which we can choose different ways to project words on screen. The act of embedding words on screen, especially words next to faces and bodies, can embody how we communicate through words, images, and our bodies in interaction. However, to make the aesthetic message rhetorically effective and visually accessible to audiences, each user would have to make deliberate choices in how best to convey meaning through words on screen. While we might not be able to educate every single user of informal social media platforms, we and those in our networks—including in our professional and academic contexts—can support each other’s alignment of accessibility and aesthetics in our video composition processes.

While I do not claim to set down in stone best practices or exemplars of online platforms amid rapidly changing online contexts, the benefits and limitations of different styles of visual text across different screens can certainly be recognized. If current and future generations dedicate more time and space to vertical videos with visual text embedded, we can commit to improving how the visual text embodies accessible multimodal communication in these contexts.

While Miles included the words of lyrics through visual text, not all creators use the visual text to create word-for-word captions. Often, the visual text is used to symbolize messages not actually spoken on screen, as when someone places one word on screen for 10 seconds and speaks a completely different statement. With TikTok’s introduction of automatically generated captions, users can provide word-for-word captions that are turned on and off by their viewers. The layers of embedded text and automatically generated captions create a whole new dilemma, as revealed by Emily Lederman (2022) in her graduate capstone project, “An Exploration of Accessibility and Captioning Practices on TikTok.” Lederman reviews the accessibility and captioning options available on TikTok, analyzes tweets, and presents findings from her survey of 67 DHH and hearing participants and their experiences with TikTok captions. Among other significant points, the results reveal the limitations of automatic captions that include errors, the limited number of TikTok videos with captions, and the challenges of double captions being displayed in videos.

There are two different kinds of double captions to keep in mind. One case occurs when a creator creates open captions that they add to the bottom of the screen, and also provides closed captions of the same exact words. When open captions are embedded at the bottom of the screen, if closed captions are turned on, sighted viewers will see two lines of captions (closed captions layered on top of open captions). In such cases, sighted viewers need to turn off the closed captions and read only the open captions, as shown in Figure 7.8 showing a video by Christine Sun Kim.

Figure 7.8: Double captions that occur when captions are embedded at the bottom of the screen and closed captions are turned on

In other cases, those who create videos and embed highly dynamic visual text on screen without fully transcribing every word being expressed in the video can create conflicting layers. A common practice with vertical videos is to embed specific words as dynamic text that stays on screen for a certain period of time while different words are being spoken or expressed in the video. However, if the dynamic text is embedded at the bottom of the screen and word-for-word lines of captions are generated, the captions will block the viewer’s visual access to the dynamic text—and thus the holistic experience of video.

The concept of double captions should prompt content creators to embed open captions or visuals away from the bottom of the screen so that closed captions can be displayed separately from and not on top of key visuals on screen. That way, the layers will not interfere with each other and can be read separately.

Ideally, however, vertical video content creators should design a space for both visual text and full captions: consider carefully the placement of all of your components when you embed excerpted visual text and convey the fully spoken or expressed message through word-for-word captions.

WHAT CAN YOU DO AND NOT DO?

As we create space for visual text and captions, findings from researchers in human-computer interaction, user experience design, and related fields can inform our understanding of the affordances of visual text in online videos. Early experiments with dynamic captioning and subtitling demonstrated approaches to kinetic typography that embodies rising pitch or loudness (Forlizzi et al., 2003), emotive captioning that use typography to visually represent emotional content (Fels et al., 2001; Fels et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2007; Mori & Fels, 2009), and visualizations of music (Fourney & Fels, 2009). The dynamic nature of subtitles should be moderate, though, and not extreme, as suggested by Rashid et al.’s (2008) comparison of user responses to three levels of captioning: conventional captions, enhanced animated captions, and extreme captions that provided sound effects around the screen while there were also captions on the bottom of the screen at the same time.

Brown et al.’s (2015) assessment of hearing participants’ reactions to dynamic subtitles indicates participants’ positive feedback to how dynamic subtitles make it easier to follow the action when they are integrated into the frame rather than at the bottom of the screen. The reactions seem to show that integrating subtitles into videos improved the aesthetic quality, the usability, and the users’ sense of involvement with the video content. Other researchers have specifically explored the benefits of developing systems that would place subtitles closer to speakers and regions of interest on screen (Akahori et al., 2016; Mocanu & Tapu, 2021; Tapu et al., 2019). Social media captions and subtitles are a relatively underexplored field, and it is important for those of us who analyze and create videos to endorse the inclusive design of accessible and aesthetic videos in vertical and horizontal formats.

We should always be acutely aware of what we can do with our text and the limitations of the video editing software or automatic generators that we use, such as what is provided by each social media platform. As van Leeuwen (2014) writes of kinetic typography, “The software designer has decided what moods will exist and how they are expressed. The software designer has created the language with which you are to express your ‘mood.’… The question has to be asked: What can you do … and what can you not do?” (p. 23). Van Leeuwen’s question rings true for any technology and social media platform we use as we create captions and embed visual text on screen to embody our messages.

What we can do is commit to aligning accessibility with aesthetics as we embody our messages through multiple modes in interaction. We can meaningfully integrate words in the space next to us instead of randomly embedding colors and emojis around the screen. We can, as the characters and the creators have shown us throughout the previous chapters of this book, commit to the interdependent, interactional process of committing to access and design a meaningful space for captions.

JUXTAPOSITION: CAREFUL CONSIDERATION OF CAPTIONS AND SUBTITLES

Throughout this book, I have shared my videos in which my predominant approach has been to integrate black subtitles in the space next to me near my face and upper body. As discussed in the final chapter, that subtitling approach provides access to my professional message within this book’s context. In my video for this chapter, words are used on screen to visually demonstrate the message that creators should carefully consider best practices for integrating captions and subtitles in online contexts. As you watch this video, consider the limitations of randomly creating highly visual text for social media videos.

In this video, I briefly incorporate some words in colorful text to show what happens when we change the audience’s reading experience. First, I include only the words, “visual text” in blue—a color that is relatively more accessible than other colors when considering colorblindness and other factors—within a sentence about visual text in videos, and follow that up with another sentence that includes the word “positive” in blue. These two sentences demonstrate modest incorporation of colorful words in a relatively accessible color. These two sentences model my balance of accessibility and aesthetics.

To counterbalance a rhetorical use of color, I then follow that up with two subtitle blocks that are entirely in blue to replicate social media videos. Those are followed by a sentence in which I say, “But we should not just add any color or any style,” with the first three words in different colors. That embodies my argument that just adding any color or style can render our words inaccessible and ineffective. Through this design, I show and tell audiences that careful consideration must be paid to our typographical choices, including how and why we are choosing different colors, sizes, or fonts.

Creators can and should likewise consider the best rhetorical and design approaches for their own videos and balance aesthetics with accessibility. We can all carefully consider effective design practices for captioning and subtitling our videos so that we can make our spaces of communication more accessible. As the affordances of technologies continue to evolve, we can all continue to engage in conversations about effective practices for captioning and designing videos.

SHOW HOW IT SOUNDS

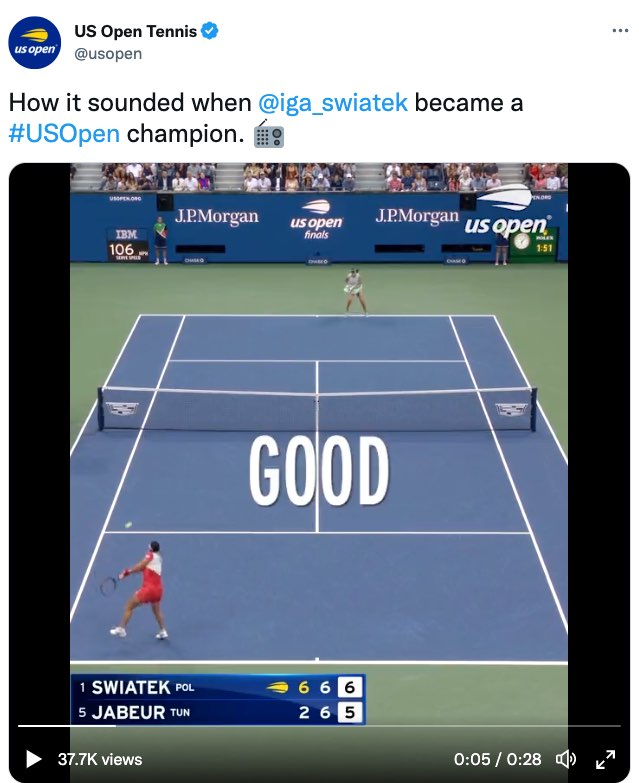

Conversations about and through captions and subtitles and visual text occur not only by talking about captions, but just as effectively by embracing and valuing the fluid interplay of visual, textual, and sonic modes. The multisensory vibrations of sound and emotions can be conveyed through visual incorporation of prominent words on screen, as captured in a video that U.S. Open Tennis posted on Twitter (now X) in September 2022 after Iga Świątek of Poland won the U.S. Open Tennis Championship.

The supersized emotions that tennis fans feel when watching the gripping decisive moments of a final, and the thrilling moment of victory, are heightened through this online version of the match that originally aired on television. When watching a live television match, caption readers are presented with captions for words uttered by commentators several seconds earlier. In essence, caption readers are in two timeframes at once as we continually reconcile the rapidly unfolding live action with the commentary that is being typed on screen several seconds after the fact. Our access is further limited by the fact that key utterances by officials on court, including “out,” “fault,” “let,” and other decisions are often not captioned. Viewers rely on the visual action, players’ reactions, and the commentators’ explanation several seconds later, to determine the result of any point.

Limited access to real-time sounds in televised tennis has its opposite in the highly engaging video that U.S. Open Tennis (2022) posted after the match that accompanies a post that states, “How it sounded when @iga_swiatek became a #USOpen champion.” This 28-second video starts with the final moments of the match and immediately places large captions right at the center of the court—and the video. We are shown each word that is uttered at once, word for word, as shown in the following screenshots (Figures 7.9, 7.10, and 7.11).

Figure 7.9: A tweet that includes a video with large open captions that emphasize the calls in a tennis match

Figure 7.10: A tweet that includes a video with large open captions that emphasize the calls in a tennis match

Figure 7.11: A tweet that includes a video with large open captions that emphasize the calls in a tennis match

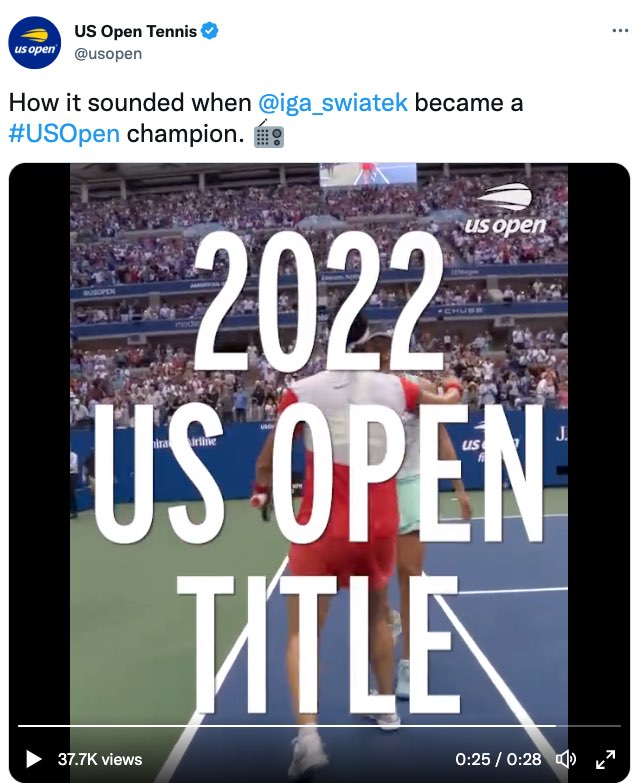

As a viewer of televised tennis for the past 20 years, I was astounded by the level of access I had to the sounds and the heightened emotion of this moment. Watching this video over and over, not only do I experience for the first time direct access to every single decision being uttered in real time (“FOR SWIATEK,” “FOREHAND CROSS,” “MISSES,” “LONG”), I feel the anticipation, the increase in excitement, and the collective exhilaration. I feel, hear, and sense the collective celebration as she wins the “2022 US OPEN TITLE.” That visualization is shown in the following screen captures (Figures 7.12, 7.13, and 7.14).

Figure 7.12: A tweet that includes a video with large open captions that emphasize who won the 2022 US Open Title

Figure 7.13: A tweet that includes a video with large open captions that emphasize who won the 2022 US Open Title

Figure 7.14: A tweet that includes a video with large open captions that emphasize who won the 2022 US Open Title

This visualization of words brings the viewer into the multisensory space of Arthur Ashe Stadium. While accessibility might not have been the driving force behind the creation of this video, this video clearly embodies the benefits of multimodal, multi-textual communication in connecting with audiences.

PROMOTE THE VALUE OF MULTILINGUAL SPACES

While we can celebrate the multi-textual integration of sound and visuals and concede that English is a common language in the international world of tennis, we should also recognize the limitations of this video in communicating solely through English. Other multilingual spaces show us the power and affordances of captions and subtitles in bridging multiple languages. In order to fully celebrate these spaces, we need to begin with the problems of limited access to multiple languages.

I consciously do not use the word “foreign,” including when discussing ASL and Spanish in our multilingual society. However, as a closed caption reader, I am too often exposed to the phrase, “[speaking foreign language]” during live televised settings and prerecorded films and television programs in which the captioner might not know or type out the actual language being spoken. That phrase fails to convey which language is being spoken as well as the actual words being spoken in that language. For instance, if individuals are speaking Spanish, then, certainly, these words should be typed out in Spanish to honor and recognize the intrinsic value of all languages, cultures, and identities.

The value of incorporating different languages in closed captions became apparent on social media and traditional media when the closed captions for CBS’ live telecast of the 2023 Grammys only displayed “SINGING NON-ENGLISH” during Bad Bunny’s Spanish and English opening performance of a medley from his album, Un Verano Sin Ti, and “SPEAKING NON-ENGLISH” during his Spanish and English acceptance speech for winning the award for Best Música Urbana Album (Hailu, 2023; Schneider, 2023a, 2023b). This clear conversation, and CBS’ subsequent addition of Spanish-language captions in replays of the Grammys, foregrounded the value of inclusive captioning practices and a shared commitment to recognizing multiple languages in the same space.

This communal action reminded me of another moment in which closed captions—and the lack of access to multilingual dialogue—were spotlighted, but not to the same degree of action that effected change. Back in 2019, I watched the first Democratic debate of the 2020 election cycle and had seen the closed captions read “[SPEAKING FOREIGN LANGUAGE]” when several candidates spoke in Spanish, including Julián Castro, Beto O’Rourke, and Cory Booker. The next day, I watched a replay of The Late Show with Stephen Colbert’s monologue in which the politically attuned host critiqued the debate (The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, 2019). While Colbert and his writing team took a comical take on different moments from the debate, an important takeaway for me was that Colbert’s reaction spotlighted the limitations of writing “[speaking foreign language]” in closed captions for audiences.

Early in Colbert’s monologue, he shows a clip from the debate in which O’Rourke switched to Spanish. He remarks, “This is true—in the closed captioning, it said, just said ‘speaking foreign language.’” To show that, The Late Show inserted a frame of the debate with the closed captions they had on screen and enlarged the closed captions to visually emphasize the phrase, [SPEAKING FOREIGN LANGUAGE] (as depicted in Figures 7.15 and 7.16).

Figure 7.15: Colbert’s observations of how “[speaking foreign language]” is used in closed captions

![Colbert's monologue continues with the closed captions reading, "just said, ‘speaking foreign language.’" There is a screen capture of Beto O'Rourke from the debate with closed captions from the debate that read, "[speaking foreign language]."](images/colbert_2_justsaid.jpg)

Figure 7.16: Colbert’s observations of how “[speaking foreign language]” is used in closed captions

Colbert then laughs and remarks, “Really got through! Really penetrated!” Throughout the rest of his monologue, as he continues to critique the debate itself, he uses “speaking foreign language” as a recurring theme, including, “The moderators were not ready to take ‘speaking foreign language’ as an answer,” and “I don’t speak ‘foreign language’” (Figure 7.17).

Figure 7.17: Colbert’s reaction to how “foreign language” is used in closed captions

Although Colbert takes a comedian’s take on the portrayal of Spanish in the closed captions, this spotlights the immense significance of authentically representing our languages in our captioning and subtitling practices. As captioners ourselves, we must break down—rather than create—linguistic and cultural barriers and extend bridges across languages.

While Colbert was making fun of the closed captions in the original debate, The Late Show’s closed captions for Colbert’s monologue used the line “Speaking Spanish” instead of showing the actual Spanish words. Indicating the actual language is absolutely a major step forward; now, how could we go even further and include the actual language itself in our captioned and subtitled spaces?

HONOR MULTIPLE LANGUAGES IN THE SAME SPACE

The Sunday after Bad Bunny performed at the 2023 Grammys stirred up Super Bowl and cultural conversations about that year’s Super Bowl advertisements. Three of these advertisements, shown to millions of people, portray multiple languages in interaction with captions and subtitles. Together, these advertisements promote (in addition to their products), the value of inclusion and access to each other’s messages while, unfortunately, replicating the reality of mistranslations and mis-transcriptions.

As shown in Figures 7.18 and 7.19, McDonald’s 2023 Super Bowl commercial featured rappers Cardi B and Offset along with a montage of other couples addressing the camera about their relationships and knowing each other’s fast food order as a sign of love. While most of these conversations are in English, one spoken line is in Spanish, with closed captions showing a woman speaking about her partner’s order. While the attempt to be more inclusive in the captions and subtitles makes the meaning more accessible, the words are unfortunately mistyped and represent the language inaccurately, such as the misspelling of sorpresa, or surprise.

Figure 7.18: Closed captions for English and Spanish speech—with errors in the Spanish captions—in a McDonald’s commercial

Figure 7.19: Closed captions for English and Spanish speech—with errors in the Spanish captions—in a McDonald’s commercial

Just as the mistake is unfortunate, this incorporation of Spanish in closed captions is a too-rare recognition of the value of multiple languages in our society, and we must commit to more inclusive captioning and subtitling practices that would be faithful embodiments of our languages and identities, including accent marks. At the same time, we should consider how to make meaning accessible across languages to those who might not know a language.

The value of multiple languages extended to two other 2023 Super Bowl advertisements that incorporated subtitles. General Motors and Netflix’s collaborative commercial (General Motors, 2023) showed Will Ferrell incorporating electric vehicles in different Netflix programs. The commercial includes a moment from Squid Game with English subtitles showing the translation for the Korean dialogue, “You moved!” and “I did not.” The closed captions in Figures 7.20 and 7.21 replicate these words in English with description in brackets showing that the speaker is using Korean.

![Will Ferrell is shown in a scene from Squid Game along with other individuals, all wearing the same green tracksuit. Open subtitles read, "You moved!" Closed captions at the very bottom of our screen read, "[In Korean] You moved."](images/netflix_1_youmoved.jpg)

Figure 7.20: Open subtitles and closed captions for Korean speech in a commercial for General Motors and Netflix

![Will Ferrell is shown in a scene from Squid Game along with other individuals all wearing the same green tracksuit. Open subtitles read, "I did not." Closed captions at the very bottom of our screen read, "[In Korean] I did not."](images/netflix_2_ididnot.jpg)

Figure 7.21: Open subtitles and closed captions for Korean speech in a commercial for General Motors and Netflix

The New York Mets’ (2023) commercial, shown to regional viewers, centered on the concept of “We wanna hear you,” as in, “We want you to buy tickets and come to our games.” The commercial showed Mets players at an office taking calls from fans. One of these players was simultaneously on the office landline and on a video call with Kodai Senga on his smartphone. Senga’s Japanese speech is subtitled in English, as shown in Figures 7.22 and 7.23.

Figure 7.22: International communication and subtitles for Japanese speech in a commercial for the New York Mets

Figure 7.23: International communication and subtitles for Japanese speech in a commercial for the New York Mets

The subtitles and captions in these scenes call on viewers to read these speakers’ messages as opposed to listening to a translator. Directly reading their messages embodies the multilingual and multicultural worlds we navigate through, including the international media we watch and the international members of the “local” teams we root for.

These linear captions and subtitles do not dance around the screen yet are just as rhetorically effective in embodying the connections we form across languages, cultures, and identities in our interdependent commitment to designing inclusive spaces.

COMMUNICATE IN ANY LANGUAGE

The cultural conversations around “speaking non-English” expanded when Bad Bunny hosted Saturday Night Live (SNL) in late 2023, reflecting the affordances of using captions and subtitles to convey meaning across multiple languages. Bad Bunny’s episode was multilingual, with several sketches including some spoken Spanish (particularly a sketch about telenovela actors and actresses) and with the closed captions for DHH audiences showing the words in Spanish—a rare instance of having access to the original language through closed captions.

The cultural power of captions and subtitles was conveyed in Bad Bunny’s opening monologue satirizing the 2023 Grammys’ depiction of him as “speaking non-English” (Saturday Night Live, 2023a). Although he begins his monologue in English, he soon switches to speaking in Spanish. Suddenly, large open captions appear on screen for all sighted viewers, reading, “[SPEAKING IN NON-ENGLISH].” Bad Bunny interrupts his own monologue when he notices the open captions, and calls for the captions to be changed. Figure 7.24 shows Bad Bunny pointing to the open captions; the real closed captions appear at the top of the screen and show DHH audiences what he is actually speaking at that moment: “Cámbienme eso. Cámbienme eso.”

![Bad Bunny is standing on stage in front of the “Saturday Night Live” house band. He is gesturing to open subtitles at the bottom that read, "[Speaking in non-English]." Closed captions appear at the top of the screen in Spanish: “Cámbienme eso. Cámbienme eso.”](images/snl_badbunny_1_speakinginnonenglish.jpg)

Figure 7.24: Bad Bunny speaking in Spanish when hosting Saturday Night Live

In response, the open captions are changed to “[SPEAKING A SEXIER LANGUAGE].” The audience laughs and applauds, and Bad Bunny gives two thumbs up, as shown in Figure 7.25.

![Bad Bunny, in the same scene, has thumbs up. Open subtitles at the bottom read, "[Speaking a sexier language]." Closed captions appear at the top of the screen: "[Cheers and applause]."](images/snl_badbunny_2_speakingasexierlanguage.jpg)

Figure 7.25: Bad Bunny celebrating Spanish when hosting Saturday Night Live

While this demonstrates how captions and subtitles can embody access and connections across languages, the very next moment eliminates some of the victory, as the host then gestures to the captions and says, “You know what? I don’t trust … this thing,” and brings in his actor friend Pedro Pascal to translate for him instead. Although this might seem to be an unfortunate instance of suppressing captions and subtitles, the monologue should be celebrated for honoring multiple languages.

Another sketch in the episode satirizes the Age of Discovery and is entirely in spoken Spanish (Saturday Night Live, 2023b). This pre-recorded sketch shows explorers who have returned from the “New World” and who show their king and prince their “discoveries,” such as the tomato. The actors in this four-minute sketch all speak Spanish, and open English subtitles appear at the bottom of the screen throughout the entire sketch. Just as thrillingly, the closed captions provide access to the speakers’ original language by transcribing Spanish. Figure 7.26 shows this mix of languages with open subtitles at the bottom of the screen providing the translation for spoken Spanish. The closed captions at the top of the screen provide DHH audiences with sound descriptions in English such as “[Laughs]” along with the original spoken words in Spanish.

![Bad Bunny is in costume as a Spanish king from the Age of Discovery. Open subtitles appear at the bottom that say, "Just what we wanted, dad." Closed captions appear in Spanish at the top that read, "[Laughs] Exactamente lo que queremos, papá."](images/snl_badbunny_3_justwhatwewanteddad.jpg)

Figure 7.26: Subtitles and captions in a pre-recorded Saturday Night Live sketch

While including open subtitles may be more feasible with pre-recorded content, this sketch and episode is a unique instance of accessible multilingual communication on SNL and shows the rich potential for captions and subtitles in enriching humor and connections across languages. There is much potential for providing more deep and richer access to sound and languages through captions and subtitles.

EMBODY THE FLUIDITY OF LANGUAGES

The international connections that we all engage in daily occur when watching interviews with international players on our home teams or at sports tournaments or international content through streaming providers, or when interacting with others on social media. All these moments are opportunities for challenging monolingualism and accessing meaning across languages, including with captions and subtitles as bridges that bring modes, languages, and individuals together.

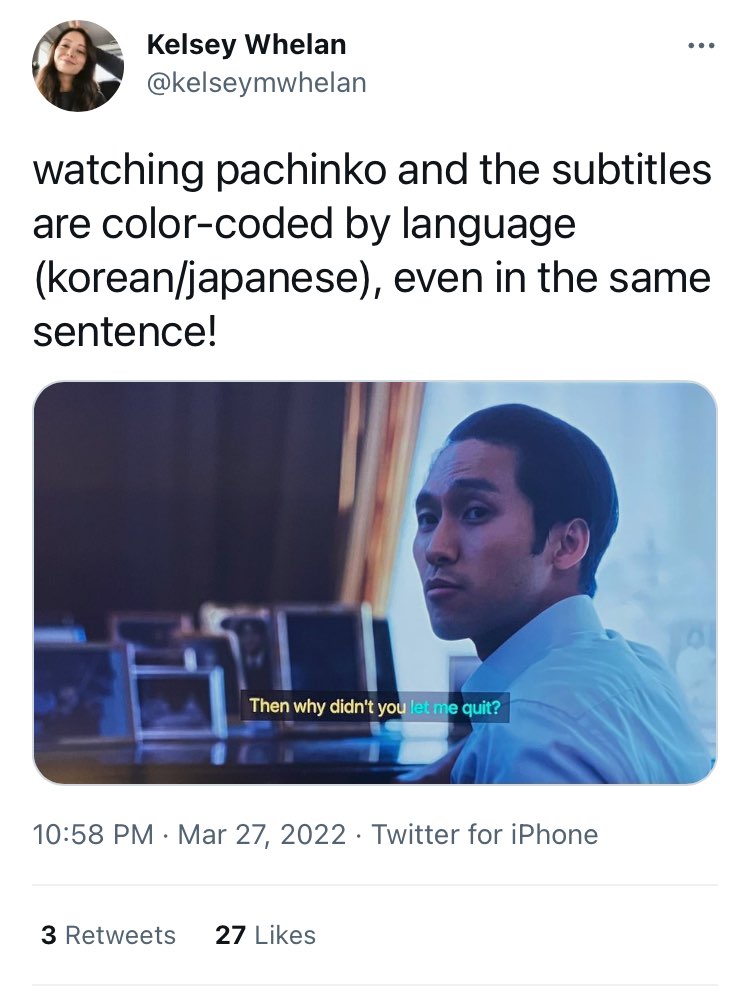

One notable challenge to monolingualism comes in the multicolored subtitles for Korean, Japanese, and English in Apple TV+’s Pachinko, a show in which the predominant languages are Korean and Japanese as detailed by Sonia Rao (2022) in a Washington Post article. Open subtitles appear on screen in yellow when characters speak Korean and in blue when characters speak Japanese. If the viewer has the Apple TV+ option for English captions turned on, these captions appear in white. As detailed by Rao, series creator Soo Hugh felt that it was “intuitive” to color-code the languages in the subtitles so that audiences “outside Korea and Japan” would know when “the languages handed off” (n.p.). This was important not just for knowing which language is which, but also because the show would not be able to work if “we as an audience aren’t able to feel the fluidity of how language works in the show—and also the restrictions of it and the imprisonment of it” (Hugh, as quoted in Rao, 2022, n.p.). This audience awareness enhances the rhetorical, aesthetic, and accessible qualities of Pachinko.

The fluidity of language is made explicit in the subtitles for the character Solomon, since, as Rao (2022) explains, “the yellow and blue capture how his Korean heritage both challenges and intertwines with his Japanese upbringing” (n.p.). This visualization is conveyed through a tweet in which a viewer (Whelan, 2022) highlighted the use of different colors for different languages (Figure 7.27).

Figure 7.27: A tweet highlighting Pachinko’s color-coded subtitles

Rao (2022) details another powerful scene that uses the visual representation to provide audiences with access to “power dynamics between the characters,” such as one scene in which “the blue and yellow subtitles denote two simultaneous, contradictory conversations” (n.p.). Hugh explains in Rao’s article how characters who can “traverse between different languages” have “access to both places” (n.p.).

Through this simultaneous textualization and visualization of multiple languages in interaction, this series creator capitalized on the affordances of subtitles in embodying the experiences and rhetorics of each character through multiple languages. The actors did not need to act with space for subtitles next to them to make the subtitles essential.

The visualization of languages in subtitles is essential to the meaning of this composition, and we can likewise make captions and subtitles meaningful embodiments of our rhetorics and our commitment to access and inclusion.

MAKE CAPTIONS AND SUBTITLES CENTRAL IN OUR CONVERSATIONS

The growing trend of including captions and subtitles on our shared screens, from television to smartphone screens, leads to affirming the importance of making captions and subtitles accessible in several related ways: easily read, readily available (easy to turn on or already open), and easily shared with others. Through the continual dissemination of videos with captions and subtitles, we can show, not tell, that captions and subtitles are central in our conversations and our commitment to connecting with each other.

One such space in which captions and subtitles have become more prominent is in the form of interviews shared as vertical videos. With different individuals appearing at the top and the bottom of the frame, these become natural spaces in which captions and subtitles are placed in the center, anchoring the two parts of the vertical frame. That in turn can support viewers’ abilities to saccade from one individual’s statements and face to the next.

Content creator Melissa Elmira Yingst, who is Deaf and the host of the online series Melmira, exemplifies the power of storytelling and connection within and across communities through her online videos. While she has for many years published traditionally horizontally framed in-person interviews as well as Zoom interviews with traditional subtitles, she has more recently published versions in vertical format for viewing on a smartphone. Her vertical interviews literally place captions and subtitles at the center of the interview, as shown in Figures 7.28 and 7.29 (Yingst, 2022b, 2023).

Figure 7.28: Interactions with CAS at the center of vertical videos

Figure 7.29: Interactions with CAS at the center of vertical videos

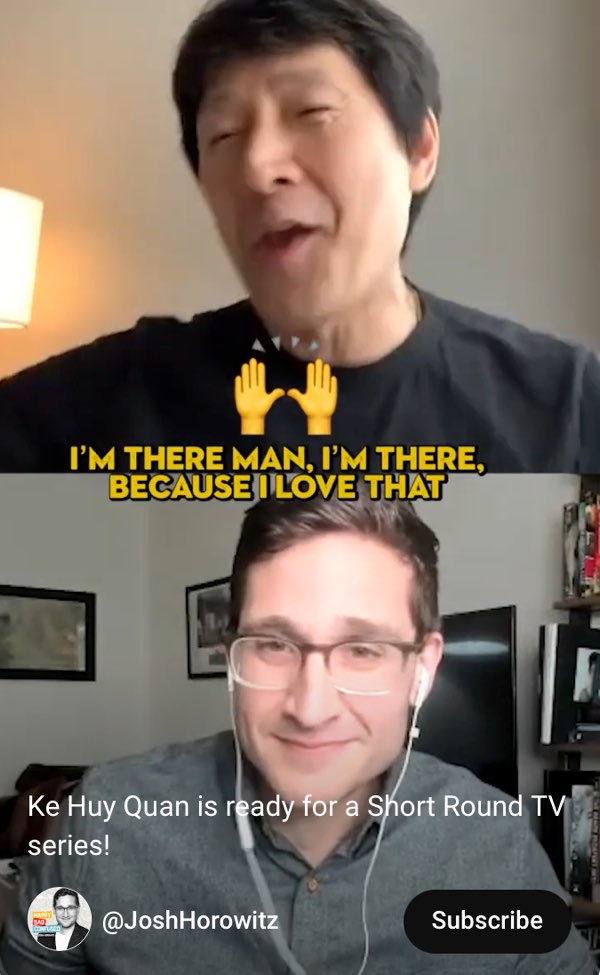

Yingst is far from being the only one to centralize captions in these vertical interviews. The commonality between Yingst’s Deaf spaces of communication and others’ hearing spaces with spoken communication shows an alignment, or overlapping, of benefits for communication. Podcaster and host Josh Horowitz, who interviews celebrities from a range of backgrounds and publishes the full interviews in horizontal mode, including on YouTube, has also marketed his interviews through short-form vertical videos that embed open captions in the center of the screen. One such example comes from his interview with actor Ke Huy Quan (Horowitz, 2023), as shown in Figure 7.30.

Figure 7.30: Written words and emoji at the center of a vertical video

Horowitz’s (2023) and others’ vertical videos appeal to viewers on smartphones and, through the natural incorporation of captions, they become accessible. However, the principles of accessibility are not consistent across video genres or platforms since the open captions often only appear in the short vertical video version of these spoken interviews, including through YouTube Shorts and other social media platforms. When watching these full interviews on YouTube, in which the two images are placed side by side (instead of vertically) the viewer has often been left with automatically generated captions that are relatively more difficult to process.

With more content creators producing short-form vertical videos, including through YouTube Shorts, captions and subtitles are literally becoming central in more of our spaces without the participants pointing out or commenting about the captions and subtitles or, in too many cases, even thinking about access itself. However, by incorporating captions and subtitles as a natural component of the vertical video for audiences to read in a variety of contexts (including without the sound on), content creators contribute to the multiplication of captioned videos and the familiarity that audiences (who might also be content creators) have with seeing captioned videos. Through this acculturation and enhanced values for words and images on our screens, content creators can, whether intentionally or not, contribute to the accessibility of our spaces and conversations.

With this, we come full circle among advocates who clearly and directly call for captions and access to those who contribute to access without realizing it. The multitudes of stories, rhetorics, and knowledge collectively co-exist as individuals of all kinds are exposed to different experiences, captions and subtitles approaches, and strategies for connecting with audiences and creators. This is exemplified through Yingst’s (2022a) interview with Deaf rappers Warren “Wawa” Snipe and Sean Forbes about their experiences performing in ASL during the 2022 Super Bowl and their desire, as captured in Figure 7.31, for “more visibility” in the world at large.

Figure 7.31: Visibility and CAS at the center of a vertical video

We can continue to visualize the many ways that individuals express ourselves, including the benefits and limitations of each approach, and collaborate in the ongoing process of designing access and connection across our communities and cultural spaces so that each one perceives and senses the power of our differences and commonalities.

CONCLUSION: MAKE CAPTIONS AND SUBTITLES PART OF OUR CULTURES

These are crucial thematic principles: we can design dialogic space for captions online, align access and aesthetics, and critically reflect on the affordances of our captioning and subtitling technologies. We can create captioned access to the multisensory experience of sound, promote and honor the value of multiple languages in the same spaces, embody the fluidity of languages, and make captions central in our conversations. These are not fixed skills or technologies to use, but values for our society as each one of us commits to visualizing captions and subtitles as the embodiment of accessible multimodal, lingual, textual communication in our cultures: music, sports, politics, the news, entertainment, and everything in between.

Through each moment, we reflect the embodied multimodal approach of designing a space for captions and subtitles and access, creating visual or multiple modes of access, embodying our rhetorics and experiences, communicating through multiple modes and languages, enhancing the rhetorical and aesthetic qualities of a video while showing awareness of how audiences may engage with and access our composition. These principles ring true across different screen-mediated contexts and stages, as evident through another study on theater captions in which D/deaf, hard-of-hearing, and hearing participants underscored the value of balancing creativity and the art of the show with accessibility so that one does not outweigh the other and that we always work to ensure that our art is accessible (Butler, 2023b).

Our desire for connection should motivate us to keep captions and subtitles part of our cultures while we continue to always recognize the benefits and limitations of communicating through written text in interaction with other modes.