While Sherlock and Heroes Reborn integrated subtitles into the space around hearing actors, in this chapter, we will design a (Deaf) space for connections to fully appreciate how the meaningful integration of captions and subtitles can create greater opportunities for experiencing embodied differences and multisensory connections. To first understand the principles of Deaf Space and Deaf Gain is essential to prepare for our subsequent deeper dive into the holistic experience of Gallaudet: The Film, a short silent film.

In an article in Rhetoric Review (Butler, 2018b), I briefly analyzed how Gallaudet: The Film designs a Deaf Space for words on screen, particularly in classroom moments from this film. The accessible and aesthetic design of captions and subtitles in this film shows us the value of designing spaces for learning through differences on our screens.

(DEAF)SPACE FOR CONNECTIONS

This chapter’s centering of the Deaf experience extends the work on Deaf Gain circulated by Deaf Studies scholars Dirksen Bauman and Joseph Murray (2014). Deaf Gain frames being Deaf not as a hearing loss, but as a valuable visual-spatial sensory orientation, or gain, that can contribute intrinsically to mainstream and hearing society (Bauman & Murray, 2014). Deaf Gain and Deaf Studies scholars maintain that hearing “individuals would be enriched by becom[ing] a bit more Deaf … more acutely aware of the nuances of communication, more engaged with eye contact and tactile relations … [and] more appreciative of human diversity” (Bauman & Murray, 2010, p. 222). Reimagining captions and subtitles is certainly Deaf Gain, and a creative gain, that can benefit the world of communication. Take Armstrong (2014) and his statement that, “investigation of Deaf Gain has the potential to influence the productive use of the new communication technologies… [and the] capacity to communicate using the visual medium” (p. 88). With this in mind, it becomes apparent that the potential for captions and subtitles to embody the many ways that we all communicate is great.

The embodied nature of multimodal communication might be at its most salient in conversations between two members of Deaf culture moving through spaces together, such as down a hallway, as shown in Figure 3.1 from a video about Deaf Space (Vox, 2016).

Figure 3.1: Visual text on screen showing how Deaf Space includes space to sign

Through our embodied rhetorics—our Deaf rhetorics—we sign and respond to each other’s movements and maintain constant eye contact while we cue each other in to sounds or sights that may be out of the other’s periphery. This commitment to maintaining visual and spatial connections as we move through shared spaces informs the design of integral captions and subtitles that embody multisensory connections, as evident in Gallaudet: The Film, a short silent film that embodies Deaf cultural values.

Before analyzing the film, it is wise to begin with exploring the concepts of Deaf Space as a Deaf Gain in an enactment of Brueggemann’s (2013) celebration of “deaf insight” and her (2002) call for us to consider how experiencing the world through deafness, blindness, or a “disability enables insight—critical, experiential, cognitive, and sensory” (p. 321). The insight created by being Deaf is sensed in the DeafSpace1 Project at Gallaudet University, which was directly informed by the values that Deaf people place on embodied communication and continual visual connections. In a signed TEDx Talk entitled “An Insight from DeafSpace,” Robert Sirvage (2015), a design researcher for the DeafSpace Project, demonstrates the importance of signers maintaining eye contact and a sense of trust as they navigate space in coordination and co-construct a panoramic visual space through the intersectionality of their eye gaze as they create a 360-degree view of what is happening all around both of their moving bodies.

The intentional design of barrierless spaces extends ASL users’ “shared sensory reach” (Figure 3.2), as shown in a video about Deaf Space (Vox, 2016).

Figure 3.2: Visual text on screen showing how Deaf Space supports shared sensory reach

The cultural commitment to facilitating embodied communication is echoed by Hansel Bauman (2014), an architect involved with the DeafSpace Project, as he explains how participants in a signed conversation interact with and through the space around them. Reflecting the importance of mobility, proximity, and flexibility, the conversation circle or triangle changes dynamically in shape and size as participants join and leave the conversation (pp. 390–391). The architecture principles of DeafSpace embody these physical relationships as “derived from the innate desire for sustained interpersonal and spatial connection” (p. 391).

The principles of DeafSpace—“architectural patterns addressing space, light, composition, order, form, and materiality”—originated in a 2005 DeafSpace Workshop at Gallaudet University (H. Bauman, 2014, p. 380). The workshop led to the DeafSpace Project, a three-year design-and-research course at the ASL and Deaf Studies department, that developed an architectural language for expressing “the dynamic connection between space, place, and human relationships” (H. Bauman, 2014, p. 381). These collaborations in turn led to groundbreaking projects designed with DeafSpace patterns on the campus of Gallaudet University in 2008 and 2012 and were embodied in 2010’s Gallaudet: The Film.

Sirvage himself conveys the complementary nature of DeafSpace in Gallaudet: The Film when he is shown presenting on Deaf Space and describing how the practice “transcends the notion of access and pursues aesthetics,” as shown in Figure 3.3. Accessibility and aesthetics are embodied in this space.

Figure 3.3: Design researcher Robert Sirvage presenting on Deaf space in Gallaudet: The Film

The “unique sensory and spatial dimensions” of the design coordinate with “visual language and deaf sensory abilities” in ways that reflect and express Deaf culture (H. Bauman, 2014, p. 379). Instead of hard corners, soft curves are used; instead of closed rooms, there are open spaces; instead of blocked views, there are clear views from different angles. In this way DeafSpace creates “a visually legible environment as a fabric, weaving together visual cues about destinations, pathways, and the use of space seamlessly” (H. Bauman, 2014, p. 386).

A core component of DeafSpace is its practice as an actively participatory process. DeafSpace architect David Lewis says, “This isn’t about accommodating…. It’s actually about using the deaf experience as a challenge to make better space” (as cited in Stinson, 2013, n.p.). DeafSpace “does not focus on issues of accommodation, but rather on Deaf cultural aesthetics that are embodied in the built environment” (Bauman & Murray, 2010, p. 218).

When space is designed, it becomes embodied rhetoric rather than an object because it becomes a meaningful and aesthetic part of communication. Take Hansel Bauman’s insistence that instead of adapting buildings to meet the needs of deaf people, we can move to “creating an aesthetic and meaning that emerge out of the ways deaf people inhabit and construct their spaces” (2014, p. 378). Leigh et al. (2014) note that “this [design] aesthetic has been around for a long time, as witness buildings that are open and airy in space” (p. 358). However, the potential has been largely untapped, just as the potential for intuitive captions and subtitles has been relatively underexplored in videos.

DeafSpace may be designed particularly for Deaf individuals, but those involved insist that many others could benefit from thoughtful design. Bauman and Murray (2010) explain that although Deaf Space generates “from designing the optimal environment for Deaf signers, the basic precept is that Deaf space principles would create exceptional buildings for everyone, regardless of audiological status” (p. 219). Stinson (2013) reports that:

[Lead architect David] Lewis is quick to point out that DeafSpace principles could (and perhaps should) be the basis for any architecture project. Oddly enough, it seems like having all senses intact has a way of dampening our expectations—we start to make excuses for clunky architecture and unintuitive design, mainly because we’re capable of navigating those obstacles without too much trouble. (n.p.)

Let us transition from architectural space to video space.

DEAF SPACE ON FILM

Deaf Space as the aesthetic design of flexible space for embodied communication is a driving principle in the design of Gallaudet: The Film (Bauman & Commerson, 2010), an eight-minute silent production that embodies the ethos of the nation’s only liberal arts university for DHH students. Narration and dialogue are written throughout the campus of Gallaudet University on screen as viewers are immersed into a multidimensional space created by and for visual-spatial connections.

This eight-minute film involved over 200 members of the Gallaudet community, and the producing team included current and former faculty members and students, including producer Dirksen Bauman, director Ryan Commerson, director of photography and editor Wayne Betts Jr., and set designer Ethan Sinnott. With a mostly Deaf filmmaking team, it should be little surprise that the film itself is completely silent. The fluidity of the camera with the captions and subtitles becomes a form of Deaf rhetorics and embodied rhetorics—or the construction of meaning through the body in interaction with the world around us. The interpretation of meaning through ASL and English words intermingling on screen enriches the multisensory experience of the Deaf world that is in Gallaudet.

Bauman and Murray (2014) describe the soundless film as “one example of a culturally deaf aesthetic within filmmaking” (p. xxxi). The beginning of Gallaudet: The Film establishes the multisensory experience of interconnected and embodied space by drawing viewers into Deaf Space: the camera zooms into an artist’s sketchpad of a tree which transforms into a man’s sign language performance of a tree with roots extending around and into the body. The man’s ASL performance ends with trees appearing around him and extending to audience members seated in front of him. They visually applaud (by silently oscillating their hands in their air) as the camera smoothly pans around the room to show us their faces. It is as if we are gracefully navigating through the room to meet each person as white text appears around their bodies with their names, alumna years, and job occupations. The effect is that we become part of the multilingual community and its roots without a single sound—and without a single cut.

The seamless integration of visual text extends to integral captions and subtitles as the camera continues to move amongst these individuals’ bodies and guides us outside into the night. The camera pans around the nighttime outdoors space as white handwritten captions gracefully appear on the upper right area of the screen. “Language and culture are the roots that intertwine to define human identity, to affirm one’s existence” appear on screen in three lines, but not all at once. Instead, a few words appear on screen in sharp white font while others stylistically fade into the background to pace viewers through reading the subtitles and absorbing the message. The white font against the dark background keeps the attention on the words while the background scenes move us through Deaf Space, as shown in Figures 3.4 and 3.5.

Figure 3.4: Visual handwriting that is written across a dark night scene in the form of silent narration

Figure 3.5: Visual handwriting that is written across a dark night scene in the form of silent narration

Whereas mainstream filmmaking practices may impose voice-over narration in such scenes, these handwritten captions enhance visual access to meaning and the aesthetic qualities of the video: we are traversing through the significance of this culture and its history. Each line in the textual narration gradually appears on screen to become crisp white text and then fade away as the next line appears on screen. This blurring effect—in which certain phrases and words blur on and off screen to provide emphasis to each other—guides us through the significance of the message: the value of language, culture, and identity.

The cultural values of visual fluidity and panoramic sense of connection with spaces and places are recreated through the constant movement of the camera and the captions. The camera does not cut between scenes; rather, the aesthetic sense of flow immerses us into this world. The embodied journey through Deaf history and culture visually guides viewers towards a beautiful sunny day around Gallaudet campus in which the captions appear in the center of the screen connecting the blue sky with the green grass.

In the same handwritten font as earlier in the film, we experience the value of history and identity. Each phrase and word in the statement gradually appears on screen and begins to move up towards the sky and be erased as the next line appears in its place. As shown in the following captures (Figures 3.6 and 3.7), the subsequent line in turn moves up toward the sky and gracefully disappears as the successive lines and words appear to finish the powerful statement: “History has carved a path toward equality and justice … toward a future of innovation and prosperity.” These words appear around the middle of the screen and move up as they fade out, keeping the viewer’s eye in the center of the screen—the meaningful part of the scene—as we travel through Gallaudet campus on a bright day with students walking around.

Figure 3.6: Visual handwriting that is written across Gallaudet University’s campus in the form of silent narration

Figure 3.7: Visual handwriting that is written across Gallaudet University’s campus in the form of silent narration

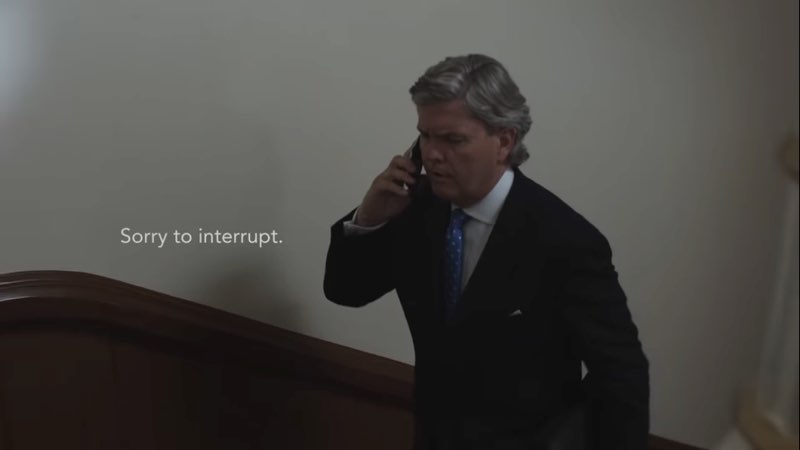

To fully experience the value of integrating fluid captions and subtitles, the flow of the camera a few moments later shows a man walking up a staircase while talking on his phone (although no speech is made audible). The captions indicating his speech appear in a contemporary sans serif font in the spaces around him as he travels up the staircase. After he turns to take the next flight, the captions appear on the other side of his body to accompany his body’s change in direction. The captions do not appear all at once; rather, they scroll in and out to accompany the temporal pacing of his spoken words (Figures 3.8 and 3.9).

Figure 3.8: Integral captions that stay next to a speaker in motion.

Figure 3.9: Integral captions that stay next to a speaker in motion.

After he removes his phone from his ear, he and viewers read a sign on an easel that states he is entering a Deaf Space Institute workshop titled “Architecture Shaped by Our Bodies,” hosted by Gallaudet University.

We accompany this man in entering the workshop space, and before we even see the bodies in the space, italicized subtitles on screen tell us what the Deaf Space presenter is signing in the room. As shown in Figures 3.10 and 3.11, we and the man enter the space and see the presenter, the next lines immediately appearing in the space under the presenter’s body.

Figure 3.10: Integral captions and subtitles that appear near signers and speakers in interaction.

Figure 3.11: Integral captions and subtitles that appear near signers and speakers in interaction.

This continuous moment in which the subtitles direct our eyes to the appropriate location on screen encapsulates the cultural values of visual flow, eye contact, and designing a space for embodied communication.

As the man navigates through the room and finds a seat in the triangular-shaped table, we experience the presenter’s statement: “We look at human sensory experience and we also look at how our language influences the way that we occupy space.” As the man sits down, the camera pans around to a seated participant who speaks in response to the presenter and the subtitles appear by the respondent’s body. The conversation continues as the presenter, and subtitles by his body, show that “Deaf Space transcends the notion of access and pursues aesthetics.”

The presenter’s integrally subtitled and signed statement is powerful. Deaf Space is space designed for and by Deaf people, so embodied communication is organically infused into every rounded corner. The buildings—and this video—are not assembled for only functional purposes to ensure that certain bodies can walk from one side to the other with ease. Rather, these community places are developed to embrace shared sensory orientation and seamless visual-spatial conversations. The wide walkways and clear views enhance the agreeable experience of moving through space seamlessly; sharp corners, steep steps, and small rooms are barriers that need to be navigated around and visual-spatial obstructions that take away from the aesthetics of a building. With its aesthetic and embodied design, Deaf Space is a pleasing atmosphere in which visual-spatial communication flourishes. The use of integral captions and subtitles likewise moves through Deaf Space in a way that could not encapsulated through conventional subtitles at the bottom of the screen.

To show how Deaf Space pursues aesthetics, Sirvage and the camera move to a model that represents Deaf Space and then the camera dives into the model, which transforms into a computer animation. Without a single cut, we are led to a classroom setting.

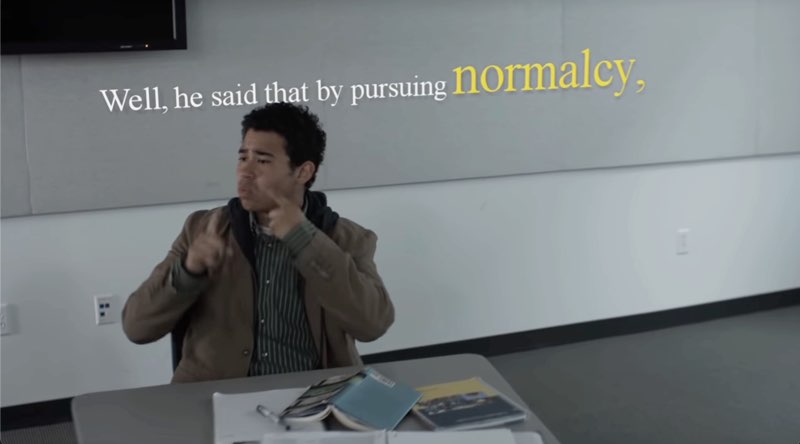

This critical classroom scene encapsulates the cultural values of Deaf Space, eye contact, visual flow, and circular connections. The instructor and students are seated in a circle and engaging in a signed discussion as integral subtitles appear in the spaces around their bodies to guide us not only through their signs but also through the connections they are making with each other. The camera never stops as it pans the room showing different bodies and perspectives to embody Deaf rhetorics in a shared space.

Allow me to pause again to contextualize the classroom scene. This scene guides viewers through what film producer Dirksen Bauman (2015) describes organically as the “deaf classroom ecology” that is always fully or semi-circular so that all participants can establish eye contact and connections with every other participator. In his critique of how being hearing limits the way we shape our built environment, Bauman challenges the seat and row configuration of conventional classrooms that lack human connection and create isolation in the classroom. A professor of Deaf Studies at Gallaudet, he argues that knowledge gained from sign language changes how we approach language and “the meaning of text,” particularly “how humans learn through visual, gestural, and spatial modes [in ways that have really] increased our access to knowledge.”

The deaf classroom ecology in this scene in the film and the accentuated subtitles intensify the connections between instructor, students, and viewers in accessing meaning across multiple modes and languages. The instructor, Lindsay Dunn, begins with the key question, “Is the concept of ‘beauty’ universal across cultures?” Each word appears in tandem with his signs and the term “beauty” appears in yellow font to stand out against the other words in white font and emphasize the concept to be discussed: beauty.

As in Figures 3.12 and 3.13, the camera rotates around the instructor’s body while the subtitles stand still next to his body; the camera travels through the subtitles. In the same movement, the camera turns behind the instructor’s body to show the students and the back of the subtitles in reverse. This unique design effect of the subtitles aesthetically and rhetorically presents his question to the students—to students and viewers who can visually access his embodied rhetorics.

Figure 3.12: Integral subtitles that stay right next to an instructor who is signing as the camera moves around the room

Figure 3.13: Integral subtitles that stay right next to an instructor who is signing as the camera moves around the room

The aesthetic design of subtitles continues with the first student to respond. She is seated at her desk and the subtitles appear in alignment with the desk in front of her as if she were holding a sign in front of her. This succeeds in making the textual display of information as important as the signed statement, rather than delegating subtitles to a subservient position. This student discusses the contrasting standards of beauty across time, the time eras appearing in yellow text to reinforce the difference between the standards of the past and the standards of the present. Each word that she signs quickly flips up, creating a full sentence. That sentence remains on screen as she signs new words that then replace the words already on screen one by one; in this way, the standards of the past flip into the standards of today.

The signed responses and questions of the other students occur organically as we move around the room experiencing different perspectives and the subtitles appear in the spaces around their bodies (Figure 3.14). The aesthetic design of the subtitles transcends access to different modes of communication by intensifying the interpersonal connections created between Deaf bodies in this classroom ecology.

Figure 3.14: Integral subtitles that appear right next to a student who is signing

The transcendental scene nears an end when we view the instructor from the students’ perspective, his opening question, “Is the concept of ‘beauty’ universal across cultures?”—appearing softly and set back near his seated body. He is not stating the question at the moment, but the driving topic of the discussion remains open to embody the meaning that is being considered by those in the room.

To continue the discussion, his next signed question appears in larger and brighter font next to his body, and on top of the faded original question (Figure 3.15). The effect is as if he has written the question on the board, and it remains visually accessible to the students. The scene ends with a view of the instructor from the students’ perspective as a student responds “media” with the subtitles appearing in mirror reverse to reflect how we are viewing the instructor from her angle. While the instructor would theoretically be able to read the subtitles from his position, we are on the student’s side and see the reverse figure. This is the multimodal, multilingual interpretation of embodied space.

Figure 3.15: Integral subtitles that show the sequence of questions asked by the instructor

Although the film guides us through Gallaudet and its members for another two minutes, this classroom scene is the pivotal moment that shows how Gallaudet: The Film encapsulates Deaf rhetorics, Deaf Gain, and Deaf Space in ways that transform conventional expectations about the design of videos. Viewers are guided through a world where the absence of sound might not be missed and where meaning is made through the visual-spatial-gestural interaction of bodies and modes. The camera flows through scene after scene to connect all these spaces into one Deaf Space. The intricate integration of subtitles throughout the various scenes becomes the embodied rhetorics of fluidity in spaces. The subtitles are not added to provide access to meaning; rather, they are rhetorical and aesthetic components of the film to become one with the space around them.

By reorienting viewers to the fluidity of embodied communication through spaces, this film shows the potential for challenging conventional practices in today’s screen-mediated world. This film shows that sound is not necessary for creating mood or atmosphere and that subtitles do not have to be accommodations added to the bottom of the screen. The silence is an explicit message that is a part of the rhetorical and aesthetic quality of the Deaf film—yet, incorporating audio descriptions of the visual text, captions and subtitles, and movements would be necessary to encapsulate this perceptual experience for different bodies.

DEAF LENS

The limitations of mainstream filmmaking practices that do not consider embodied multimodal communication are underscored in a signed TEDx Talk by Deaf filmmaker Wayne Betts Jr. (2010), who edited Gallaudet: The Film. During his presentation, in which he reflects on his filmmaking practices and shows moments from Gallaudet: The Film, he reveals that he creates films with the clear intention of embodying the world through his “Deaf Lens,” including the cultural values of eye contact and visual-spatial fluidity. He further demonstrates how mainstream filmmaking practices such as the reliance of sound in off-screen narration and other techniques do not reflect his experience. Rather than accepting audio-centric filmmaking practices, Betts directly challenges the conventions through his Deaf embodiment so that he could make “a Deaf film.”

One such rule that he challenged was the use of camera cuts to flip back and forth between two hearing speakers. After performing the camera abruptly cutting back and forth between two speakers, he explains2:

I looked at this uniform practice and when we talk in ASL, do we carry on conversation facing one another [flipping back and forth abruptly]?

… [Shakes his head to show no, we don’t do that.]

We normally maintain eye contact throughout the conversation. Even when we’re walking, we maintain eye contact in conversation. Telephone poles come between us, and we still maintain eye contact.

It doesn’t matter which direction we go or if there are obstacles. We stay connected to each other. We must be attuned to each other, so we can maintain that connection. Therefore, the camera should be fluid and constant. This will appeal to our inner values. “Yes, this is just like my world.” (Betts, 2010)

Betts emphasizes the value of eye contact, connection, and visual fluidity to reinforce the inner values of embodied communication. He also describes his use of Steadicams, or attaching the camera to the filmmaker, to embody the fluidity of visual procession and conversations in Deaf culture. He describes how “the camera bounces steadily” while he walks, which “makes me feel more connected to the action.” A sense of connection between bodies and the camera creates a fluid sense of space.

Following this statement, Betts shows a scene from Gallaudet: The Film of students signing in a classroom discussing changes in cultural perspectives of beauty. This scene uses a Steadicam with dynamic visual text emerging and fading around the screen in sync with the sign language. The camera flows around the room as individuals sign and the visual text fades in and out, as in Figures 3.16 & 3.17. The movement around the room is graceful and reflective of the continual connection that is important in communication in Deaf culture and pedagogy.

Figure 3.16: Integral subtitles that appear with words in white and yellow for emphasis while the camera moves

Figure 3.17: Integral subtitles that appear with words in white and yellow for emphasis while the camera moves

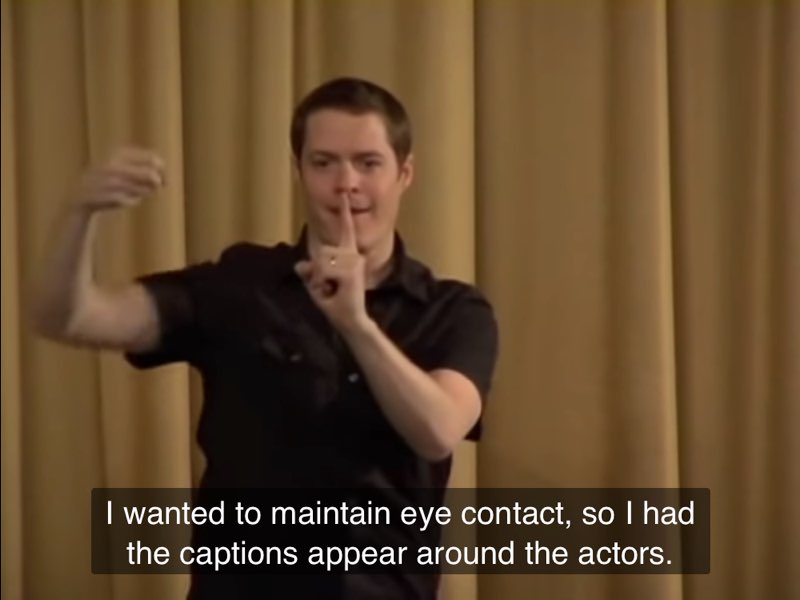

After this scene ends, Betts immediately states the following, with emphasis through facial expressions and body language (as shown in Figures 3.18 and 3.19):

Notice the captions? They weren’t fixed to the bottom of the screen [He places his hands down near the lower part of his body and keeps his lips tightly closed as the captions play near the bottom of his body. He slightly shakes his head as if something feels wrong and continues signing.]

Those captions feel just like an abrupt break in the edit. [with an emphasis on BREAK]. My eyes are drawn to the bottom of the screen. Just as I’m making eye contact with the actor, I have to look away to read the captions. [He uses his right hand to show his eyes rapidly and drastically falling down to the bottom of the screen. He repeats this falling movement again and shakes his head to show how wrong it feels.]

I want that eye contact! [with an emphasis on signs for SEE and STAY].

I wanted to maintain eye contact, so I had the captions appear around the actors. [He moves hands representing his eyes closer to the actor’s eyes to represent the eye contact].

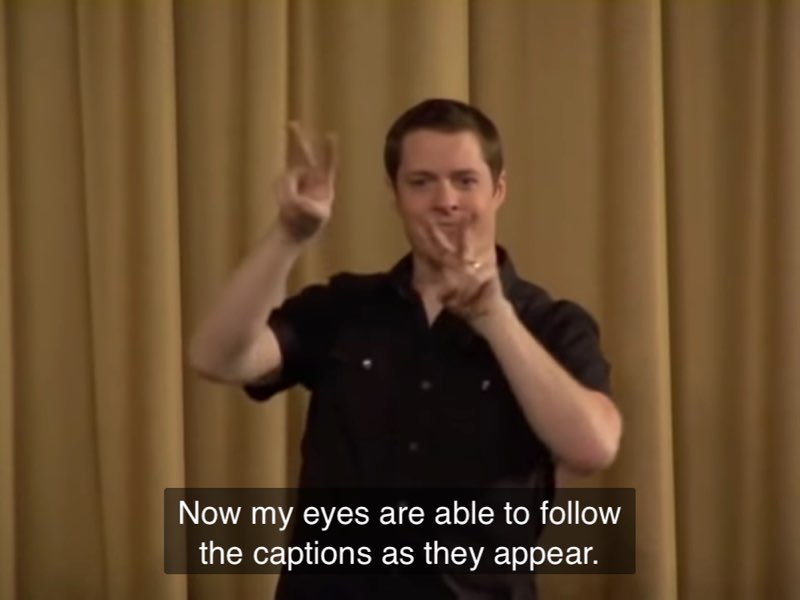

Now my eyes are able to follow the captions as they appear.

[Without shifting momentum, he keeps the hand representing the actor in front of him while his right hand becomes the captions rotating the actor to show how the captions are occurring panoramically around the actor in the scene. Smiling, his eyes look around the space in front of him naturally].

My eyes can still feel the flow in the sequence. I feel connected to what’s going on. [He nods and gently moves his connected hands to show the harmonic connection.]

And that’s my world. 3

Figure 3.18: Wayne Betts, Jr. showing the value of placing words on screen near actors to maintain eye contact

Figure 3.19: Wayne Betts, Jr. showing the value of placing words on screen near actors to maintain eye contact

This embodied multimodal statement by Betts communicates the value of integral captions in guiding viewers’ eyes through the action on screen and creating a connection between viewers and actors on screen. This embodies the value of flow, fluidity, and contact in Deaf culture. This is a deaf filmmaking practice that immerses viewers into embodied rhetorics. Instead of being trapped in film language and its sets of rules, he creates films through Deaf Lens; “It’s as if you could see the camera through my own eyes and my own perspective. See my world, how we see. Fluidly. That’s new. Deaf lens without a box. There are no limits.”

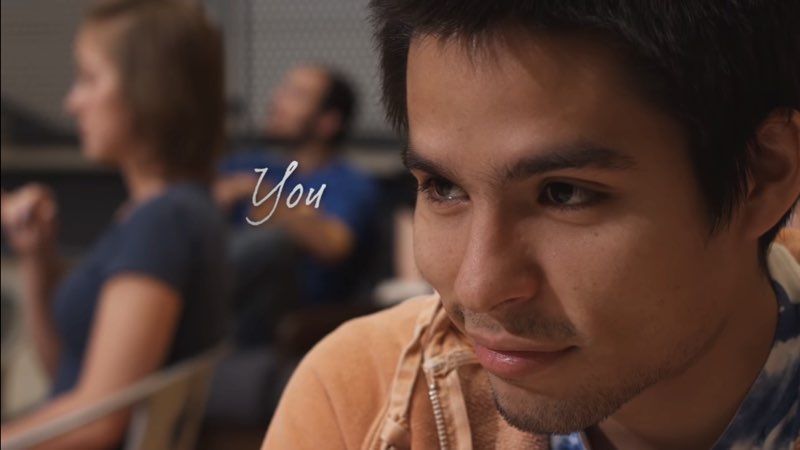

This aesthetic and inclusive filmmaking practice that embodies accessible multimodal communication with captions and subtitles on screen translates into direct connection between audiences and those in this Deaf space. We become—or are meant to want to become—a part of this world. This feeling is reinforced with the film’s concluding close-up of a confident Gallaudet student looking out into the distance (Figure 3.20). Handwritten words appear along the direction of his gaze and show us “You” (which then fades into black with white text, “You are Gallaudet”). We follow his gaze from right to left. This design and placement of the captions strengthens our simultaneous identification with this current student and this inclusive world—past, present, and future all in the same time and space.

Figure 3.20: Visual handwriting on screen that connect the eye gazes of the actor and you, the audience

These filmmaking practices reveal the affordances of integrating captions and subtitles into the space of the screen and enhancing our multisensory connections. This is a rhetorical and aesthetic gain for D/deaf, hard-of-hearing, and hearing audiences and creators.

JUXTAPOSITION: CO-CONSTRUCTION OF MULTILINGUAL AND MULTIMODAL MEANING

In full affirmation of integral captions and subtitles as a Deaf Gain for filmmaking practices, I have integrated subtitles into the space of my videos. One moment in my video for this chapter reinforces how creators can learn from Deaf embodiments and embodied rhetorics to strengthen the accessible, rhetorical, and aesthetic qualities of videos. As you watch this video, consider how creators can engage in multimodal analysis of videos with captions and subtitles.

In this moment, my signs and subtitles model the classroom scene from Gallaudet: The Film. I describe how the instructor starts with a discussion question that appears next to him, but I add to this performance by gesturing to the subtitles next to me. In similar ways, instructors who create online pedagogical content could gesture to questions placed next to them on screen. In the next part of this video, I describe how the students respond in ASL with subtitles that appear around them, and I sign right next to the subtitles to emphasize the alignment of words and signs. These interactive strategies can be used by instructors and students in course videos and projects to visually reinforce key terms and call extra attention to significant concepts on screen. Likewise, online content creators can gesture purposefully to words on screen in social media and other contexts to drive home their messages.

What is crucial when placing words on screen is this: we must be deliberate about the words that we want to place on screen and how we want to portray them so that they embody our language(s) and make our multimodal, multilingual message accessible to audiences. A careful consideration of the words we interact with on screen will remain an important element of this book, particularly in Chapter 7 when we explore conversations about captions and subtitles.

SHOW AND TELL

The journey through the Deaf spaces of Gallaudet: The Film is guided by integral captions and subtitles as multimodal enactments of embodied rhetorics. The visual text is the embodiment of accessible multimodal communication as discerned by the embodied multimodal approach: space has been intentionally designed for captions and subtitles in ways that create multiple modes of visual access to the film’s narration, signers, and ethos (principles 1 and 2); through the movement of captions and subtitles, we directly experience the embodied rhetorics and multimodal, multilingual communication practices of those on campus (principles 3 and 4); and the design of words on screen amplify the rhetorical and aesthetic qualities of this film as it shows awareness of how audiences can navigate the unique world on screen (principles 5 and 6).

Through the accessible and aesthetic design of captions and subtitles—which show and tell viewers about the Deaf world—viewers connect with those on screen and are immersed into the rhetorical space, and this consolidation may be the most effective way to activate this embodied rhetorics and embodied knowledge in the mind and heart of the viewer. While Gallaudet: The Film sets the standard high in transcending access to subtitles, it is not the only one that has integrated captions and subtitles rhetorically and aesthetically to provide visual access to embodied rhetorics. Other media in various contexts have integrated subtitles and designed a (Deaf) space for captions and subtitles.