The spaces explored up to this point have included multimodal and multilingual communication with captions and subtitles and visual text of some form on screen. These spaces prepare us for a full exploration of silence and (silent) sound as portrayed in media and embodied in creators’ compositions with the presence of captions and subtitles and visual text on screen. More specifically, I now explore examples in which sound and silence become embodied and accessible through text, as in “silent episodes” in television shows where characters do not speak for an entire episode and in video compositions where creators make perceptions of sound and silent signs accessible through written words.

The two parts of this chapter form complementary components of how sound and silence become manifested through captions and subtitles and visual text on screen. I analyze select examples of “silent episodes” of television shows that incorporate words on screen as “alternative” ways to verbalize messages. My analysis of the benefits and limitations of these methods leads to my unpacking of accessible practices by composers who manifest sonic and silent meanings through accessible and aesthetic design of words on screen as the embodiment of the multi-textual world of communication. These underutilized methods for communicating through sound and silence immerse audiences into a multisensory world in which sound and silence are sensed through the eyes and bodies as facilitated by captions and subtitles and visual text on screen, which intensifies greater connections amongst creators, performers, and audiences. What sets this chapter’s examples apart from other instances of silence is the incorporation of visual text, including captions and subtitles, that intensifies the feeling of access to embodied experiences and meaning.

While prior chapters analyzed captioned and subtitled conversations and scenes, this chapter intends to critically unpack what we learn from reframing silence and sound in our screen-mediated conversations. In essence, we can reflect on and examine the reframing of silence and sound in our drive towards a deeper recognition of the affordances of captions and subtitles and visual text on screen that embody multimodal, multisensory connections and communication.

THE SOUND OF SILENCE

While navigating through silent spaces, my embodied rhetorics as a Deaf viewer who does not find it unnatural to watch videos without sound must be acknowledged. At the same time, I have navigated through the greater world, often referred to as the hearing world, my entire life and I interact with hearing people who hold expectations for sound on a daily basis. I embrace novel approaches to sound, as in The Sound of Metal, a 2019 film that immerses viewers into the multisensory world of a hearing drummer’s gradual loss of hearing and his jarring sonic experiences when he gets cochlear implants. Riz Ahmed’s Academy Award-nominated performance and the closed captions make us literally and metaphorically hear what his character, Ruben Stone, hears at each stage of his hearing progression.

My cognitive attunement to our world of sound aligns with my embodied, multisensory, and visual engagements with sound in all its forms. As an audience member, I become the characters on my screen, who often are hearing. This is where I want to take us now: into spaces in which we sense the world differently. These spaces reframe the meaning of sound and the meaning of silence as characters and audiences engage with the world of communication in novel ways, which in turn teaches us all to expand the definitions of sound, silence, and communication.

My first experience with a silent episode came in the form of Buffy the Vampire Slayer’s 1999 episode, “Hush” (Season 4, Episode 10) (Whedon, 1999), an episode I recently rewatched as an adult along with what has long been one of my favorite episodes of the series, 2001’s “Once More, With Feeling” (Season 6, Episode 7). Buffy’s musical episode has been praised by many as one of the best musical episodes ever (Brown et al., 2021) primarily for its fresh composition of meaningful lyrics that progresses the storylines and reveals characters’ emotions as well as the actors’ masterful and heartfelt performances.

Buffy’s silent episode (Whedon, 1999), which has likewise been praised (Pallotta, 2014), was a revelation in how the wit and heart of the show and characters could be transmitted non-vocally after everyone in town suddenly could not speak. First airing on television at the turn of the previous millennium, however, “Hush” did not incorporate visual text on screen prominently. It was and is a product of its time; as shown in one scene in which Giles, Buffy’s watcher (mentor), uses an overhead projector to communicate his message to Buffy and her friends about the demons who have created this state of silence in their town, the Gentlemen.

While Giles has clearly taken the time to prepare his message by writing on a series of transparent sheets to be projected to Buffy, Willow, and the others—communicating through writing—he begins with a moment of inadvertent miscommunication caused by the technology of the time, as shown in the following screen captures (Figures 6.1, 6.2, and 6.3).

Figure 6.1: Silent communication through the technology of the time in Buffy the Vampire Slayer

Figure 6.2: Silent communication through the technology of the time in Buffy the Vampire Slayer

Figure 6.3: Silent communication through the technology of the time in Buffy the Vampire Slayer

Transparent sheets have to be placed on the projector backwards to be readable by the classroom viewers. But Giles does not realize this until his audience points out the situation. He solves the issue and continues. This communication through the projector in a highly effective silent episode uses written messages and body language to create humor and connection that would not feel the same if this occurred through their everyday spoken language.

Across time and space, what silent episodes accomplish is challenging writers, characters, and audiences to discover and construct non-vocal means of communication and connection with each other.

EXPLORING SILENCE

I want to highlight how non-vocal ways of communication and connection can be enhanced through captions and subtitles, text messaging, and other visual text on screen, which reflects the reality of our lives as we connect with each other through digital devices.

Evil, a streaming series on Paramount Plus, presented a silent episode entitled “S Is for Silence” (Season 2, Episode 7) (King & King, 2021), in which the main characters investigate a death at a monastery where silence is honored. The characters work through the mystery and interact with each other without vocally speaking a word.

One moment stands out when one character, David Acosta, struggles to suppress his inappropriate thoughts. While an average episode might use his voice-over to tell audiences what he is thinking in spoken English, this silent episode includes open captions to show his thoughts, and the captions go beyond static lines of text. As the thoughts race through his head and he starts to curse to himself, the words start to stream from the right side of the screen to the left side of the screen in a continual motion, embodying the thoughts coursing through his head. In essence, his stream of consciousness is embodied in the captions. The implementation of silence becomes an opportunity for creative approaches to communication that we might not consider or realize otherwise, and we can challenge ourselves to communicate more effectively through strategies that we have not used enough in the past.

In addition to having non-speaking characters, other programs take the approach of having characters temporarily lose their hearing. Hawkeye on Disney Plus portrays a Marvel Comics character who lost his hearing due to trauma, wears a hearing aid, and functions as a hearing person (and is played by a hearing actor). The first season of the series introduced Maya Lopez, “Echo,” an Indigenous character (who is played by Alaqua Cox, who is Deaf). She later leads her own Disney Plus spinoff, Echo.

While Hawkeye does not experiment with captions and subtitles creatively, the show portrays the communication barriers that can occur across modes after Clint Barton’s (Hawkeye) hearing aid is damaged in battle (“Echoes,” Season 1, Episode 3) (Bert & Bertie, 2021; Mathewson et al., 2021). He and his companion Kate Bishop are shown failing to communicate with each other. After one moment, Kate erroneously assumes that Clint understands her and remarks, “Hey, we’re communicating!” but the audience sees the miscommunication. In another scene, they talk to each other, not with each other, and at different times in the conversation, each one mentions that they need to walk the dog. These misconnections contrast with other moments in the episode in which they write on notepads and use text messages on a phone to communicate with each other (Figure 6.4).

Figure 6.4: Communicating silently through a text message in Hawkeye

While the moments of miscommunication are generally used for levity, they reflect the reality of struggling to connect with each other when there is a lack of communication access. In contrast, the two main characters express and receive their thoughts more clearly through writing and texting to teach other.

This same episode of Hawkeye introduces viewers to Maya Lopez’s background as Deaf person and native user of ASL, including through a subtitled flashback to her childhood and a signed conversation with her father, as shown in the following capture (Figure 6.5).

Figure 6.5: Open subtitles at the bottom of the screen for ASL in Hawkeye

These scenes work together to guide viewers through deaf experiences, including through that of a late-deafened person and that of a Deaf ASL user.

Intriguingly, Hawkeye, a show adapted from comic books, places traditional subtitles at the bottom of the screen, which stands in contrast to the integration of subtitles in Heroes Reborn. This episode of Hawkeye and other episodes in mainstream television shows with hearing characters (including short scenes in which hearing characters want to communicate from across a large room) might not always integrate words on screen—but just as crucially, writing and texting become means of access and connection to other characters.

LISTEN/WATCH CLOSELY

Multisensory, multi-textual communication—including subtitles and visual text—occurs in Only Murders in the Building across several episodes, starting with its silent episode in Season 1. It is helpful to focus on the affordances, or benefits and limitations, of such alternative approaches to embodying sound and silence in the presence of subtitles and visual text on screen.

Hulu’s Only Murders in the Building is a series in which the three main characters, Charles-Haden Savage (Steve Martin), Oliver Putnam (Martin Short), and Mabel Mora (Selena Mabel), live in the same apartment building and investigate a crime while releasing a podcast about their ongoing investigation. A recurring character on the show, Theo Dimas (James Caverly, who is Deaf), is a former resident of the building where his father still lives.

The series received attention and praise for its creative use of a silent episode without spoken dialogue (Cheung, 2021; Gajjar, 2022; Maas, 2021; Mazzeo, 2021; McCullar, 2022). “The Boy from 6B” (Season 1, Episode 7) (Martin et al. & Dabis, 2021), centers on Theo and, while the characters’ voices are not made audible, music, environmental sounds, and muffled speech (as heard through Theo) are made audible and closed captioned. The director of the episode worked with Caverly and the creative team to ground the representation, such as ensuring that Theo could always read other characters’ lips and that they would not “undermine the silence of the deaf character” (McCullar, 2022, n.p.).

While most reviews focused on the novel portrayal of an episode without vocal dialogue, I want to focus on how that episode and a later episode incorporate open captions and subtitles and visual text to embody the benefits and limitations of the multilingual and multimodal conversations that we have in our own lives. In these three episodes, Theo’s point-of-view is heightened with the presence of multiple modes of communication on screen that embody how he engages with the world. This is a major instance of Deaf representation in media—a rarity as underscored in a 2022 report about, among other points, the importance of access, captions, and authentic representation of experiences in film, television, and other media (National Research Group, 2022).

By framing the silent episode through Theo’s eyes, this episode (Martin et al. & Dabis, 2021) challenges audiences to sense the world differently. As Caverly said, “Framing the entire episode in the perspective of a Deaf person is a subversive act. It forces the audience to listen closely, but with their eyes instead of ears” (Mazzeo, 2021, n.p.). The episode itself is not presented without sound; rather, different scenes portray sound and visuals differently.

When the camera frames events and spaces through Theo’s eyes in this episode, captions and subtitles appear on screen. These captions and subtitles appear when characters, such as Theo and his father, sign in ASL so that the audience can access the meaning of these signs. When the camera shows us what Theo is looking at, such as other characters speaking to each other through spoken English, their voices are not made clearly audible; rather, what they say is embedded as open captions for us to read just as Theo reads their lips.

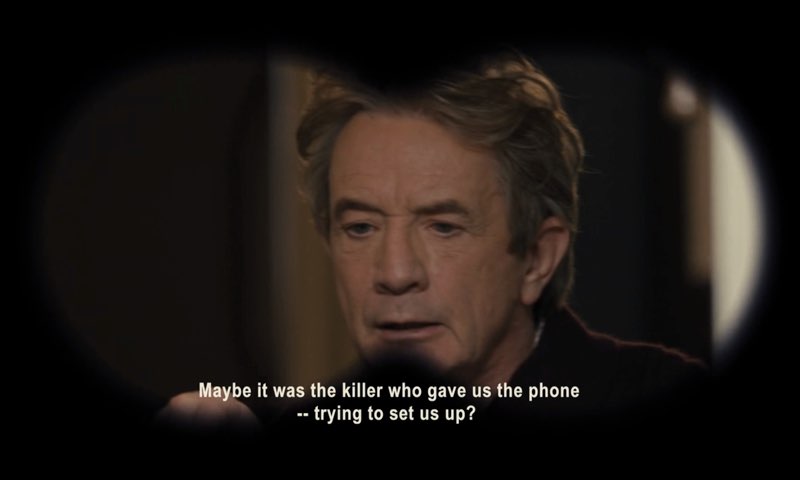

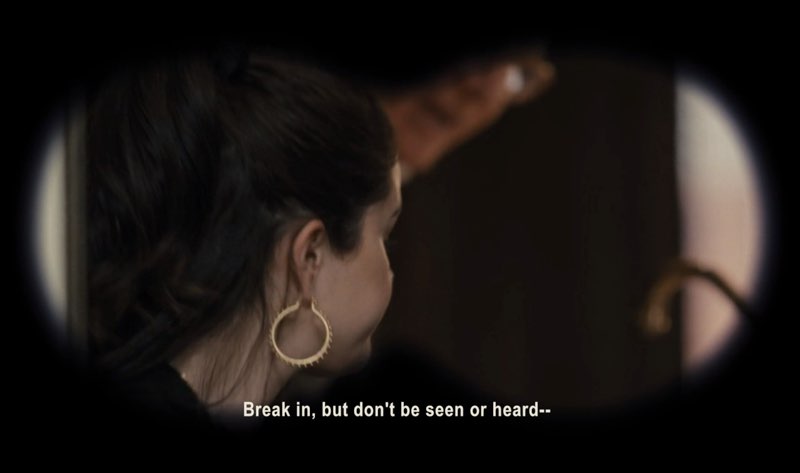

In the opening moments of the episode in this apartment building in New York City, Theo is shown spying on his neighbors, the main characters, with binoculars through his window into another apartment across the courtyard on the other side of the building. As he looks through the binoculars, open captions appear while he reads their lips, an affordance that would not be possible at that distance if relying on sound (Figures 6.6, 6.7, and 6.8).

Figure 6.6: Open subtitles showing how Theo reads characters’ lips in Only Murders in the Building

Figure 6.7: Open subtitles showing how Theo reads characters’ lips in Only Murders in the Building

Figure 6.8: Open subtitles showing how Theo reads characters’ lips in Only Murders in the Building

As we read the captions and subtitles, we become Theo who is reading other individuals’ lips or signs, including when Charles emphasizes how the three characters need to break in an apartment without being “seen or heard.” The captions and subtitles become an instrument for us to join Caverly in his portrayal of how Theo listens to and reads the world through his eyes.

Elsewhere in the episode, the three main characters continue their often humorous and entertaining pursuit of clues and discoveries as they sneak around and attempt to crack their case. They often communicate through texting each other, with these messages projected on screen as bubbles next to characters’ bodies and faces, enabling us to read the production and reception of each message and their reactions at the same time. Figures 6.9, 6.10, and 6.11 come from a scene in which Oliver, a theater director, uses text messages to connect with Charles and Mabel.

Oliver, Charles, and Mabel work together, sneaking around and spying to find out more information about Theo’s father Teddy Dimas. In this scene, Oliver is next to Teddy and has to communicate with Charles and Mabel without Teddy’s knowledge. Oliver is shown texting (in real time with letters appearing one at a time) a theatrical-themed message in code to his partners in crime so that he does not tip off Teddy.

Soon after, Charles receives another theatrical-themed text message in code from Oliver and shows his phone to Mabel. At the exact same time, the same message appears as a bubble next to Charles’s face, allowing sighted viewers to read the message at the same time as Mabel while viewing Charles’s facial expression of urgency.

![Oliver is looking down as he types on his phone, although his phone is not visible. A text message bubble appears near his face, reading, "The overture is p..." Closed captions at the bottom of the screen read, "[typing, sends text]."](images/omitb_s1_4_theoverture.jpg)

Figure 6.9: Text message bubbles on screen that show characters’ interactions

![Oliver is looking down as he types on his phone, although his phone is not visible. A text message bubble appears near his face, and the message is complete. The bubble reads, "The overture is playing, people!!" Closed captions at the bottom of the screen read, "[typing, sends text]."](images/omitb_s1_5_theovertureisplayingpeople.jpg)

Figure 6.10: Text message bubbles on screen that show characters’ interactions

Figure 6.11: Text message bubbles on screen that show characters’ interactions

What makes these text messages especially ingenious is how they prevent others around these characters from accessing their communication. We are given a portal into Charles, Oliver, and Mabel’s silent, textual conversations at the same time that they prevent the other characters in the building around them from catching them.

The incorporation of contemporary technologies is a modern-day version of Giles’ classroom projector in Buffy the Vampire Slayer and continues our very-human desire to compose our messages in any way that can be accessed by our audiences.

I DIDN’T GET ANY OF THAT

Only Murders in the Building extends its incorporation of subtitles—and the challenges of connecting with others across languages and modes—when Theo returns for two episodes in Season 2. In “Here’s Looking at You,” (Season 2, Episode 4) (Martin et al. & Weng, 2022), Oliver is spying on Teddy, Theo’s dad, through Teddy’s apartment wall and sees father and son having a heated argument in sign language. In what could be interpreted as a rhetorical move (especially in light of the creative team’s commitment to diversity and authentic representation of the Deaf character), the show does not subtitle this signed argument, underscoring how this conversation is being seen through Oliver’s perspective; Oliver does not know ASL. Oliver’s reaction makes us sense that he clearly understands enough to see the anger to know that it is not a friendly chat.

Theo plays a large role in “Flipping the Pieces” (Season 2, Episode 7) (Martin et al. & Teague, 2022), an episode in which Theo and Mabel work through attempting to communicate with each other across languages as they track down a mysterious individual, “Glitter Guy,” who had an altercation with Mabel on the subway. These challenges are represented through the mix of subtitles and visual text on screen. With this being the first real time that Theo and Mabel have interacted and Mabel being not fluent in ASL, an early interaction goes as follows:

- Theo signs with subtitles while Mabel speaks with closed captions.

- When Mabel does not understand Theo, Theo takes out his phone and shows a video of Mabel with Glitter Guy.

- Mabel speaks with closed captions and Theo gestures and signs with subtitles.

- After Mabel says, “I don’t know ASL,” Theo uses a pen and paper to write to Mabel. Mabel (and the viewer) picks up and read the note.

- Theo shows Mabel a card that explains how only a third of what people say can be caught through lipreading. Mabel picks up the card and reads the card at the same time.

- Mabel speaks with closed captions and Theo signs with subtitles.

- After Mabel does not understand Theo again, Theo takes out his notepad again.

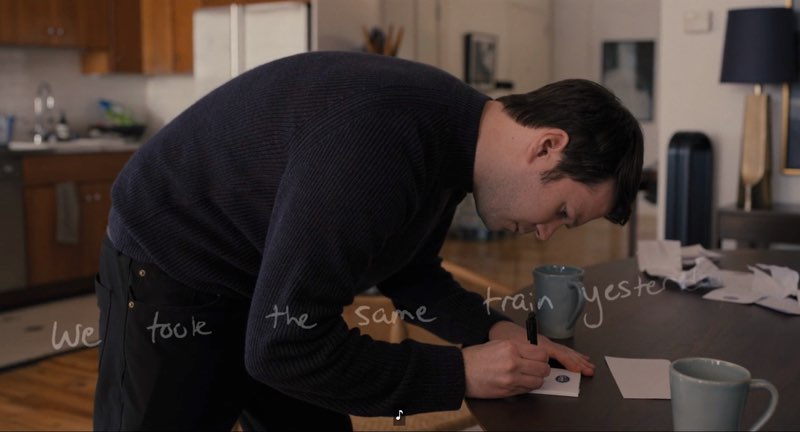

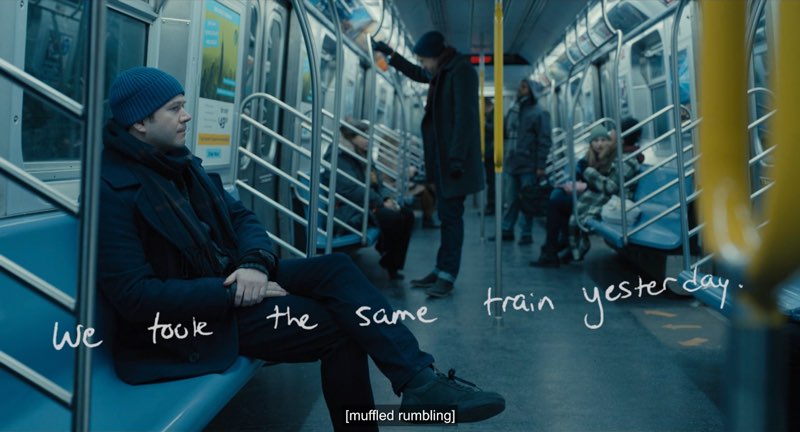

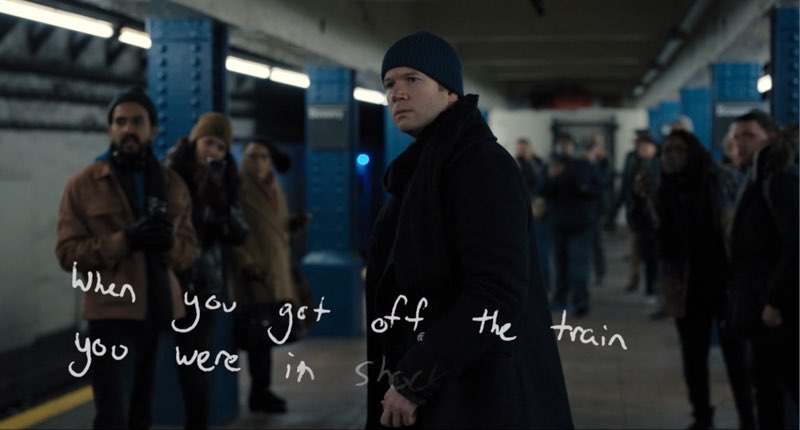

After using videos and writing to communicate, this is the moment where the screen transforms. While Theo writes down on the notepad, the visuals take us back to the subway with Theo’s written words superimposed over the action on the subway. The timing of each word’s appearance emulates Theo’s real-time writing of these words as we join him in returning to the moment of the alteration, as shown in the following screen captures of this scene (Figures 6.12, 6.13, 6.14, and 6.15).

The visual handwriting of Theo’s note transporting us in real time across the subway scene in Only Murders in the Building emulates the narration that is written across the campus of Gallaudet University in Gallaudet: The Film and the joint embodiment of fluid, visual-spatial communication.

Figure 6.12: Visual handwriting that appears across the screen as silent narration

Figure 6.13: Visual handwriting that appears across the screen as silent narration

![Theo stands up in a subway train and looks in front of him. Handwritten words are shown across the screen saying, "I saw a man." The rest of the phrase is being written out, showing "attack." Closed captions at the bottom of the screen read, "[pen scribbling]."](images/omitb_s2_3_isawaman.jpg)

Figure 6.14: Visual handwriting that appears across the screen as silent narration

Figure 6.15: Visual handwriting that appears across the screen as silent narration

The visual frame then brings us back to the handwritten note from Theo that Mabel reads. This innovative transformation of the screen to include handwritten message directly connects us with the event Theo is sharing. The handwritten message serves as what some would call a voice-over of an event in another context.

However, this is the only innovative use of visual text in this episode; the majority of the episode shows Mabel talking to Theo (with closed captions) and Theo signing to Mabel (with subtitles). Right after Mabel reads Theo’s note, she starts asking about Glitter Guy. Theo responds with the sign for glitter, as shown in the subtitles (Figures 6.16 and 6.17).

Figure 6.16: The same word being signed with open subtitles and spoken with closed captions

Figure 6.17: The same word being signed with open subtitles and spoken with closed captions

Mabel shows that she recognizes that sign and vocally states, “Is that ASL for ‘glitter’”? When Theo responds yes, she describes that as “fun.” Throughout the rest of the episode, Mabel mainly speaks and Theo signs1.

During Mabel’s and Theo’s journey through the city together looking for Glitter Guy in “Flipping the Pieces” (Episode 7), each one confesses their deep regrets. Closed captions show what Mabel says and subtitles are shown to represent what Theo signs. After Mabel tells her story, Theo signs, “Sorry. I didn’t get any of that.”

Mabel nods, sniffles, and speaks, “Maybe it’s better that way.” While they fail to fully connect, they understand enough to know how much they did not get, and they are honest about their inability to connect in this moment.

As they say goodbye in their final scene together that night, Mabel closes her mouth—reinforcing that she is not going to speak—and signs this line: “Thank you for stealing my fish.” These words are shown in open subtitles that reflect the halting pace of her signs, and then the closed captions show: “[laughs] Was that right?” In response, Theo smiles with the look of someone who has experienced this in the past and gives her a thumbs up.

This episode, as an extension of the silent episode, shows the limitations of understanding each other when only one language is expressed, such as when Mabel speaks without signing and when Theo signs and she does not understand (although the episode does seem to overestimate how much Theo can lipread, such as when he is driving and she is speaking). At the same time, the series provides audiences with access to Theo’s signs through subtitles on screen every time he signs, so that audiences know the important messages that he is expressing.

What makes this episode especially striking is their acceptance of the challenges and limitations of not accessing each other’s languages—as reflected in the subtitles and captions. Most of all, when viewed in retrospect and in light of future events in the show, we can recognize how this episode instigates the growth of their friendship.

Theo’s next appearance on the show comes in the seventh episode of Season 3, “CoBro” (Martin et al. & Dabis, 2023). Although audience members have not seen him since the previous season’s seventh episode, his first scene in this episode shows him communicating with Mabel with relatively more ease and success, and they appear to be comfortable and familiar with each other, including by making each other laugh and interacting in close proximity.

Throughout this episode, Theo continues to sign (with subtitles) while Mabel continues to speak (with closed captions), although she now signs more of what she says and understands more of his signs. They can sustain upbeat conversations throughout several scenes in this episode. The two demonstrate the growing pains of learning a new language and the advantages of playing with languages. In one scene, Mabel talks to another hearing character, trying to stealthily gather information for their murder case. Theo stands in the background silently giving Mabel cues about what to say to the other character, but no subtitles appear on screen—meaning that viewers who do not know ASL are forced to guess what Theo says, just like Mabel. In this case, Mabel misunderstands some of Theo’s signs and inadvertently says what is clearly the wrong thing to the other character, creating humorous outcomes.

A major advantage of connecting across languages and modalities also occurs in this episode. After Theo passionately shares a substantial amount of information about a movie related to their case, Mabel laughs and says she “understood maybe half of what [he] said.” However, this is not the end of her spoken remark, as she adds, “It is clear that you are a giant nerd.” While speaking, she signs the word nerd by bringing her hand to Theo’s face (instead of bringing her own hand to her own face). Through this action, as shown in the following screen captures (Figures 6.18 and 6.19), Mabel plays with ASL and connects with Theo to form one sign through two bodies.

![Mabel stands in front of Theo as she speaks. Closed captions appear at the bottom reading, “[laughs] Okay, I understood maybe half of what you said.”](images/omitb_s3_1okayiunderstoodmaybehalf.jpg)

Figure 6.18: Embodied connection across languages

Figure 6.19: Embodied connection across languages

Their friendship is evident through such interactions, and Theo proudly claims “no shame” in enjoying the movie. In a later scene, their inside joke continues as Mabel becomes the one who shares a substantial amount of information and Theo asks (with subtitles), “Now, who’s the giant nerd?”

The challenges and rewards of connecting across communication modalities continue as they now are friends. However, this episode does not incorporate visual text as aesthetically as in Theo’s previous episodes, even when Theo writes a note to another character in this episode; we are shown the notepad itself instead of words overlaid on screen.

Along with the challenges of learning to communicate in different ways is the potential for connecting more directly through visual text, as revealed in these characters’ use of various technologies, including the traditional technology of pen-and-paper as well as sending texts and showing videos on phones to illuminate meaning. This realistically portrays the different ways that we can communicate silently with each other in our lives beyond sound-centric speaking and hearing, including the benefits and limitations of trying to communicate in ways that we might be more or less comfortable with or accustomed to.

In the most rhetorical and aesthetically effective moment, the visual text for Theo’s handwriting superimposed over the flashback to the subway scene (in the seventh episode of Season 2) embodies the merging of image and text to intensify accessible multimodal communication. This integration of visual text and image reveals that the absence of sound is not a limitation, but a means of looking directly and deeply at the world—and at each other.

Space for Subtitled Silence

Several major themes emerge that we can apply in our analysis and design of video compositions as guided by the six criteria of the accessible multimodal approach. First and foremost, silent moments are opportunities for us to design a space for captions and subtitles and access so that we create opportunities for us, our dialogic partners, and audiences to access meaning across multiple modes beyond sound alone. Without relying on sound, we can attend to means of expressing our embodied rhetorics and experiences in interaction with each other as we communicate through multiple modes and languages—including the linguistic mode and written language. We can enhance the rhetorical and aesthetic qualities of our work by strategically and creatively making written text visual and integral to our message. Most of all, we can show awareness of our audiences’ expectations in several ways. We can subvert general audiences’ expectations for what they will hear and provide them with opportunities to engage with our message in ways that may be novel for them. We should provide them with multiple means of engagement and coordinate in the common process of designing accessible aural, visual, and linguistic communication.

How can we do all that? Through writing words on screen and in our lives.

JUXTAPOSITION: VIEWING THE WORLD DIFFERENTLY THROUGH CAPTIONS AND SUBTITLES

With the value of writing words on screen in mind, I now present my video for this chapter; consider how we can make our experiences of sound and silence accessible to audiences through captions, subtitles, and visual text.

In this video, I show how Only Murders in the Building uses subtitles and visual text on screen to show audiences how Theo experiences and interacts with the world. The design of open white subtitles at the bottom of the screen is used to replicate the show’s use of open subtitles. I then return to black subtitles near my upper body to continue my argument about how creators can use captions and subtitles to create access to other characters’ or individuals’ experiences of sound and silence.

Through this video, I serve as a creator who emulates different subtitling approaches to match the experience of viewing the show through Theo’s eyes. I consciously go further in my analysis and design by meaningfully interacting with the subtitles around me and drawing attention to them throughout my discussion. In doing so, I hope to accentuate audiences’ access to Deaf embodiments and embodied rhetorics, including the potential for connecting across multiple modes and senses at the same time.

Creators—such as those who incorporate sound and music in their videos, including sound studies scholars and students or online content creators—could likewise develop different subtitling and captioning styles to create access to various sonic and silent moments in videos. Through carefully designing different styles that enhance the rhetorical and aesthetic qualities of videos, we can enrich the possibilities for audiences to experience and access different embodiments and worldviews.

I DIDN’T QUITE GET THAT

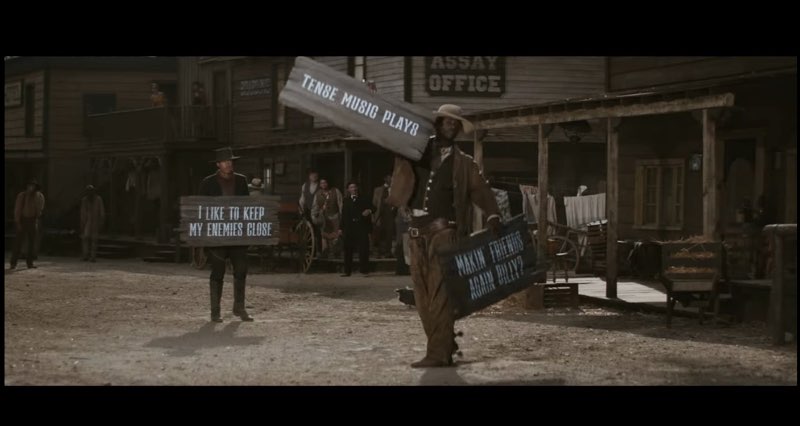

Silence becomes not the absence of sound, but rather the amplified presence of visuals in a commercial for Amazon Alexa (Bell, 2022) that plays with the concept of captioning sound. The commercial opens as a spoken interaction in the Wild West between two cowboys. They are then vocally interrupted by a hard of hearing woman on a couch who says, “I didn’t quite get that.”

Immediately, the cowboy (played by actor Monte Bell) holds up a large sign akin to a cue card, and the other cowboy holds up his own sign (Figure 6.20).

Figure 6.20: Characters in an Amazon Alexa commercial holding literal signs that caption their speech

Bell then brings out a second sign that reads, “TENSE MUSIC PLAYS” (Figure 6.21).

Figure 6.21: Characters holding literal signs that caption their speech and now description of sound

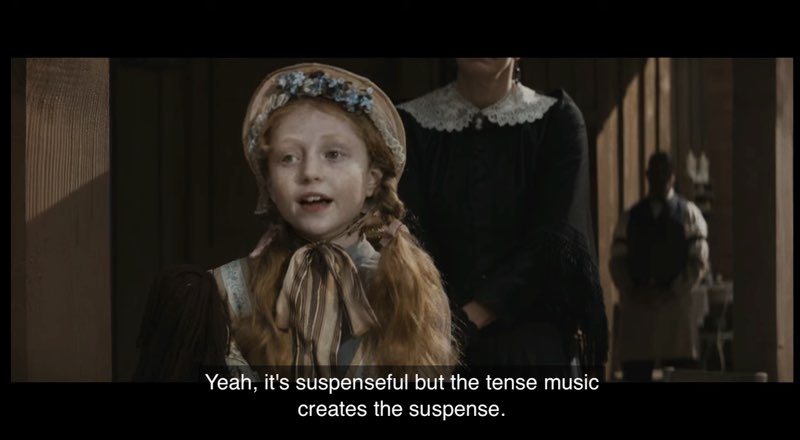

Other characters in the Wild West scene remark about the meaning of tense music versus suspenseful music. If you have the closed captions on, the captions appear at the bottom of the screen for this spoken dialogue (Figure 6.22).

Figure 6.22: Character commenting on sound description in closed captions

Bell asks them to move on, and the cowboys continue their standoff, which is now on a television screen as the camera takes us to the woman’s living room where she vocally asks Amazon Alexa to turn on the subtitles, and all viewers are shown closed captions reading “[Tense music plays].” Those of us who have turned on the closed captions for our personal devices and screens also read the woman’s spoken command to Alexa to “turn on subtitles” (Figure 6.23).

![The camera shows a television in a living room. On the television screen, two cowboys are facing each other in an outdoor scene in the Old West. Closed captions on the television screen in this living room read "[Tense music plays]." At the very bottom of this frame are our own closed captions, which read, "Alexa, turn on subtitles."](images/amazon4_alexaturnonsubtitles.jpg)

Figure 6.23: A television set with closed captions being shown on the television set—along with the closed captions turned on for this commercial

The composition of this commercial shows the possibilities in playing with layers of sound and silence and making closed captions visible to audiences.

ACCESSING SOUND AND SILENCE THROUGH VISUAL WORDS

Silent episodes can reveal the challenges and possibilities of communicating through our entire bodies. To unpack these affordances further, we can learn from composers who actively innovate and capitalize on the affordances of different modes and technologies to access the multisensory nature of holistic meaning and to make their multilayered messages accessible to audiences. Video composers, including Deaf filmmakers and filmmaking students along with artists and online creators, prove that sound and silence are not a dichotomy and we can connect in ever more nuanced ways through the interlinking of words, signs, images, and feelings in our hearts, minds, and bodies. That significance is carried through captions and subtitles and visual text on screen.

MAKING SOUND AND SILENCE ACCESSIBLE

While Gallaudet: The Film confirms the rhetorical power of designing access and aesthetics in unity through words and images moving together on screen without sound, other video creators actively engage with sonic, silent, and textual modes throughout the entire composition process. Their accessible multimodal practices and values reveal the role that captions and subtitles can play in embodying sonic and silent meaning through the textual mode and connecting creators with audiences.

Through a collaborative research project with Stacy Bick, a senior lecturer at Rochester Institute of Technology/National Technical Institute for the Deaf who teaches filmmaking and visual communications courses, a case study of her videography course was performed along with interviews with DHH students about their experiences composing with sound and captions in their video projects throughout different filmmaking and related classes.

It must be made crystal clear that students actively engage in the interdependent process of accessible multimodal composition with sound and captions. The aforementioned case study and interviews (Butler & Bick, 2021) revealed how students actively wielded various technologies and accessible and interdependent practices as they worked to accomplish their video projects. Several strategies that students use include writing captions that voice-over talent could read to produce the sound for a video; monitoring visual indications of sound in video editing programs; checking with others with different hearing levels to ensure that sound, captions, and visuals align; and using visuals to represent meaning, such as through pulsating images on screen to embody the rhythm and beats of a song.

The interviews furthermore demonstrated the value of advocating for captions, communicating with others about the importance of captions (Butler & Bick, 2023). For instance, one student purposefully designed “craptions,” awful captions with words eliminated from the captions to persuade her classmates and instructor to caption the projects that they shared in class. At the same time, these students worked to ensure that audiences with all hearing levels, including hearing audiences, could access their message by captioning and subtitling signed and sonic moments. Their direct attention to captions and subtitles as access for DHH and hearing people should be an inspiration for creators.

It is one thing to say that access is important; that value becomes so much more meaningful and authentic when we consciously and empathetically engage in the interdependent process of working together and advocating for captions and subtitles as instruments of connection in sonic and silent spaces. This value is reinforced by Buckner and Daley (2018), who embraced the collective negotiation of sound when Daley was the only deaf undergraduate student in Buckner’s Multimodal Composition course. They and the other students in the course all worked through the process of visualizing and feeling sound through different modes and ensured access for all in the course.

With full appreciation for the diversity of embodied differences and experiences with sound to silence, we can all learn from and through each other’s embodied rhetorics and knowledge in our interdependent process of accessing multilingual and multimodal communication across different contexts.

CAPTIONING THE SIGHT OF SOUND

An individual who composes with sound in novel ways is the pioneering sound artist Christine Sun Kim, who is Deaf and whose internationally renowned sound art, exhibits, and performances interrogate sound, language, and the body (McCarthy, 2020; Murad, 2022). While Kim’s profound explorations across a range of spaces exceeds the scope of this book, two of her works spotlight her perspective of sound as depicted through non-speech sound in brackets in closed captions. These artistic approaches to closed captions show us her embodied experiences while reflecting her aesthetic and rhetorical approach to artistically presenting sound through her words as a Deaf sound artist.

As part of the Manchester International Festival, Kim created a physical exhibit called “Captioning the City,” in which she composed descriptions appearing in brackets and superimposed large text on buildings and spaces around Manchester. Figures 6.24 and 6.25 come from a video of the exhibit (Factory International, 2021), which includes open captions with sound descriptions.

![A waterfront scene in Manchester with what seem to be apartments by the water. Words are placed on a building along the water. These words on the building read "[The sound of big things going over your head]." Open captions appear at the bottom of the video itself. A musical symbol appears at the beginning and end of the captions. The open captions read, "A key change brings optimism to the tone."](images/factoryinternational_akeychange.jpg)

Figure 6.24: Open captions created by Christine Sun Kim that describe sound as experienced through the body and mind

![A street scene in Manchester with a vehicle in front of buildings. Words are placed on a building in front of the street. The words on the building read "[The sound of ignorance crumbling]." Open captions appear at the bottom of the video itself. The open captions read, "Music reaches quiet and reflective finale."](images/factoryinternational_musicreaches.jpg)

Figure 6.25: Open captions created by Christine Sun Kim that describe sound as experienced through the body and mind

By literally captioning the physical spaces of the city and composing descriptive captions as part of the video, Kim makes the physicality of sound as sensed in the body tangible through written form.

The substance of sound comes forth in another artistic video entitled “[Closer Captions]” in which Kim composes rich description of sound in brackets throughout every line of the video poem (Pop-Up Magazine, 2020). Explaining that people who create closed captions “have a very different relationship with sound” than she does, she presents her visual footage and lines as “[the sound of anticipation intensifies]” (Pop-Up Magazine, 2020). Her captions are actually open captions embedded into the video, but they are portrayed in the style of traditional closed captions of white text against a black background to embody her message about closed captions.

Several of her lines emphasize the multisensory nature of sound with focus on the body, as in “[sweetness of orange sunlight]” and “[glitter flirting with my eyeballs].” Near the end of the poem, she writes, “[then the note fades away as musician’s arms drop down]” and a line with 10 eighth notes shorten as one eighth note is erased at a time, leaving one and then none. This visual playing with musical symbols reflects a visual connection with music, as shown in the following captures (Figures 6.26, 6.27, and 6.28).

![An apartment building is shown against a blue sky next to a tree. Captions at the bottom of the screen read "[then the note fades away as musicians' arms drop down]." The second line of captions shows nine musical notes in a row.](images/popupmusicalsymbol1first.jpg)

Figure 6.26: Open captions (in the style of closed captions) created by Christine Sun Kim that progressively delete musical notes to show music fading

Figure 6.27: Open captions (in the style of closed captions) created by Christine Sun Kim that progressively delete musical notes to show music fading

Figure 6.28: Open captions (in the style of closed captions) created by Christine Sun Kim that progressively delete musical notes to show music fading

Romero-Fresco & Dangerfield (2022) analyzed the creative accessibility of Kim’s captions, particularly the subjective and poetic nature of her captions (p. 23), as an example of how access can be a conversation rather than a one-way monologue (p. 28).

When we claim captions as creative works of art and access for all of us rather than tools for DHH “users,” we break open the restrictions of the screen and compose silence, sound, and everything we feel everywhere all at once. Creators of the past, present, and future embody their rhetorics and knowledge through the design of captions and subtitles.

One commonality threads through the multitude of approaches: the intrinsically undeniable value of access that captions and subtitles create (to sound, visuals, language, meaning, our place in the world around us).

FEELING THE POWER OF SILENCE

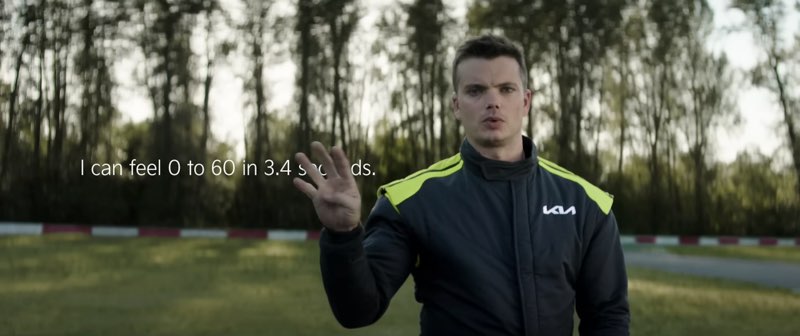

Visualizing captions and subtitles as the embodiment of accessible multimodal communication is not an activity that one sense engages in, but a multisensory experience through which audiences are invited to hear sound, see sound, and feel the vibrations of sound and silence. The tactile experience of sound becomes more accessible through Kia’s advertising campaign featuring deaf professional race car driver Kris Martin.

A television commercial, “Silence is Powerful” (Kia America, 2023), promotes one of Kia’s electric vehicles and shows Martin facing the camera and communicating through ASL to share his and Kia’s words with audiences. His signs are interspersed with footage of him racing the vehicle, inviting viewers to join him in experiencing silence in motion. Subtitles appear side by side alongside his signs to connect viewers’ eyes with his message.

The power of silence begins to be felt through Martin’s statements to the audience: “I don’t need noise” appears to his right then “to tell me something is fast” appears to his left (Figures 6.29 and 6.30).

Figure 6.29: Subtitles that appear right next to Kris Martin in a commercial for Kia’s electric vehicles

Figure 6.30: Subtitles that appear right next to Kris Martin in a commercial for Kia’s electric vehicles

ASL and English become one when Martin explains how he can “feel 0 to 60 in 3.4 seconds” and his signs for the numbers 3 and 4 move in front of the subtitles for these words next to him, as shown in the following captures (Figures 6.31 and 6.32).

Figure 6.31: Overlapping Kris Martin’s signs and subtitles in a commercial for Kia

Figure 6.32: Overlapping Kris Martin’s signs and subtitles in a commercial for Kia

Through this design scheme, subtitles and signs connect so that the subtitles are not add-ons; instead, they are integral components of our connection with Martin (and ultimately with Kia, which is promoting the relatively silent power of its electric vehicle).

With Martin as spokesperson, audiences are immersed into his experiences as a professional race car driver. He tells and shows us that being deaf since he was born taught him one thing (Figures 6.33 and 6.34): “Silence is Powerful.”

Figure 6.33: Subtitles next to Kris Martin that show the power of silence in a commercial for Kia

Figure 6.34: Subtitles next to Kris Martin that show the power of silence in a commercial for Kia

With that, we are left with the powerful sensation of silence as felt through our bodies through vibrations, other tactile experiences, and unspoken messages visualized in the form of captions and subtitles.

Just as being deaf accentuated Martin’s potential and success in his chosen profession, we can reframe access to sound and captions and subtitles through the body and continue to be committed to always learning from each other as we drive towards ever more meaningful accessibility and inclusion.

RECONCEPTUALIZATION OF SOUND AND SILENCE

Captioning and subtitling sound and silence—in physical sound art and sonic-visual poetry, in our interdependence and advocacy in our video composition courses, in our collaborations with co-creators and audiences, in silent episodes that are striking for the absence of sound—can be profound acts of empowerment and transformation. Creators with a diverse range of embodiments and relationships with sound can and do challenge the conventions, including conventional expectations of what it means to hear and expectations that media will include sound as it is “normally heard.” Creators can embody the power of silence and connect across senses.

These challenges expand the space for captions and subtitles and visual text, which are embedded with the qualities we might conventionally ascribe to other modes, including the movement of bodies in written text and the nuances of speech transmitted through words moving across the screen. Sound and silence become accessible, multi-textual means of connection—and this potential for multi-textual connection intensifies when joining conversations about and through captions and subtitles in our multilingual world.